What is the world like for the thousands of people who live in silence?

Jean-Claude, Abou, Claire, Florent and all the rest, who have been totally deaf since birth or since the early months of their lives, dream, think and communicate through signs.

With them we set off to discover that distant land where seeing and touching are of such crucial importance. This films tells their story and gives us a glimpse of the world through their eyes.

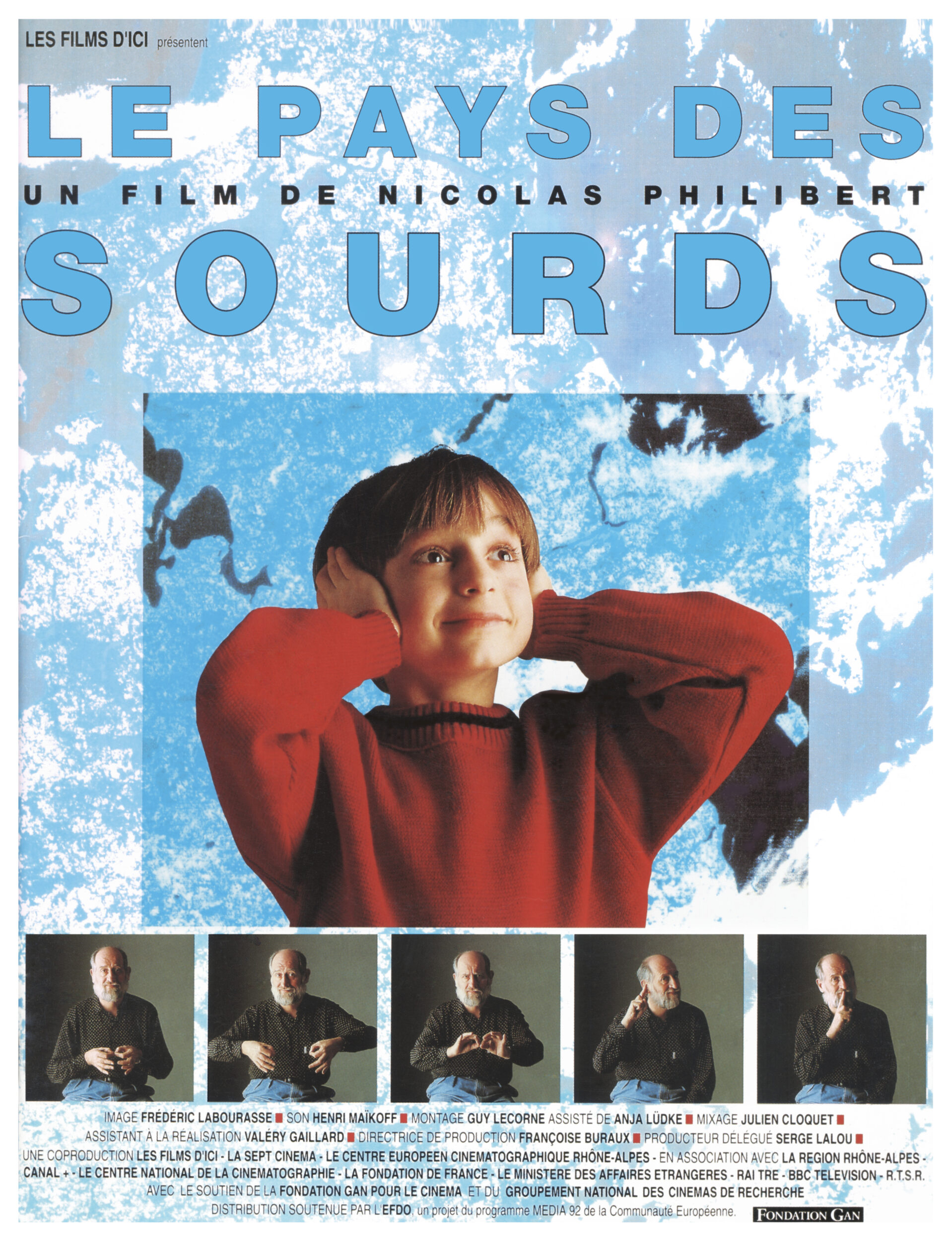

Photography and camera Frédéric Labourasse • Sound Henry Maïkoff • Editing Guy Lecorne • Mixing Julien Cloquet • Director’s assistant Valéry Gaillard • Production management Françoise Buraux • Line producer Serge Lalou • A co-production of Les Films d’Ici, La Sept-cinéma, The Rhone-Alpes European Cinematographic Centre • In association with Canal +, the Rhone-Alpes region, the Centre National de la Cinématographie, the Fondation de France, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, RAI TRE, BBC Television, Télévision Suisse Romande.

Official selection at the Locarno International Film Festival, 1992 • Selection at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, Japon, 1993 • Prix de la Fondation GAN pour le Cinéma, 1992 • Grand Prix du Festival de Belfort (France) 1992 • Grand Prix du Festival dei Popoli, Florence (Italie) 1992 • Grand Prix section documentaire, Festival de Vancouver, 1993 • Premio Tiempo de Historia , Festival de Valladolid (Espagne) 1993 • Prix Humanum, awarded by the Belgium Film Press association, 1993 • Grand Prize, Mumbai International Film Festival (India) 1994 • Golden Gate Award, San Francisco International Film Festival, 1994 – Best documentary, Potsdam Film Festival (Germany) 1994 • « Stephanie Beacham Award », 13th Annual Communication Awards, Washington D.C., 1994, Peabody Award (USA), 1997.

Distribution & international sales : Les Films du Losange

French release : march 1993

“ For the first few days of shooting, I was completely at sea ! ”

Interview with Nicolas Philibert, conducted by Georges-Henri Mauchant in 1991.

How did you get the idea for the film ?

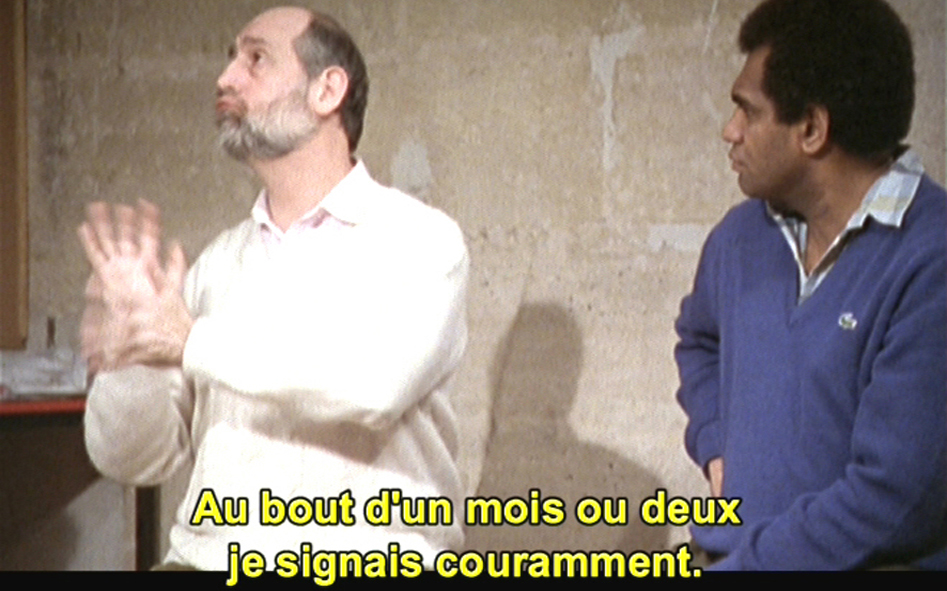

It’s a story with lots of twists and turns, and its origins go back years! In 1983, I was contacted by a group of psychiatrists to take part in the preparation of an educational film about sign language. As I didn’t know a thing about the world of deaf people, I signed up for a course in sign language which was given by a young teacher who was completely deaf himself. It was a real shock! Up until then I had seen deaf people as handicapped, period. And there I was all of a sudden faced with a man with a quite outstanding wealth of expression, a kind of born actor, capable of conveying all the shades of meaning of a thought just through the movements of his hands and the expressions on his face. For reasons which I don’t recall too clearly, the project put forward by those psychiatrists came to nothing, but for my part I started meeting more and more deaf people and I became really interested in their way of communicating. By discovering the beauty of sign language, the incredible range of its possibilities, and by also discovering the importance of things visual among deaf people, the keenness of the way they look at things, and the extraordinary visual memory they are capable of having, I started to think that a film about deaf people would be a way of “working” the very stuff of film, for the very good reason that it involves a language in which every word and every idea is translated by images drawn in space. So I wrote a fictional screenplay, but after various ups and downs, I didn’t manage to find the funding for it, and in the end I moved on to other things… But in 1991, the idea resurfaced, this time no longer in the form of a fiction film, but as a documentary, or, let’s say… a film that would tell true stories, with real characters.

What were the basic choices that steered your work ?

My idea was to make a film that would abruptly plunge the viewer into the world of deaf people, a film whose mother tongue would be sign language. If I can so put it, I wanted to let those people about whom we know nothing speak for themselves, people who have a totally different communication system from ours. My intent was to try and look at the world through their eyes. Over and above the “handicap” issue, what the film emphasizes is the existence of a real deaf culture, which has its own roots, its codes, its models, and its customs. I wanted to confront the viewer with that particular culture, not in an abstract or theoretical way, but by following various characters and telling their story. So, without any exceptions, the characters are people who are completely deaf, born deaf, or people who became deaf during the early months of their lives, in other words before they acquired language. I decided not to include “hearing-impaired people”, even though there are more of them, but this is a film, not a statistical survey! The challenge and the wager involved moving to the other side, and setting out to discover that distant “land” where seeing is of considerable importance.

How did you set about meeting the characters in the film ?

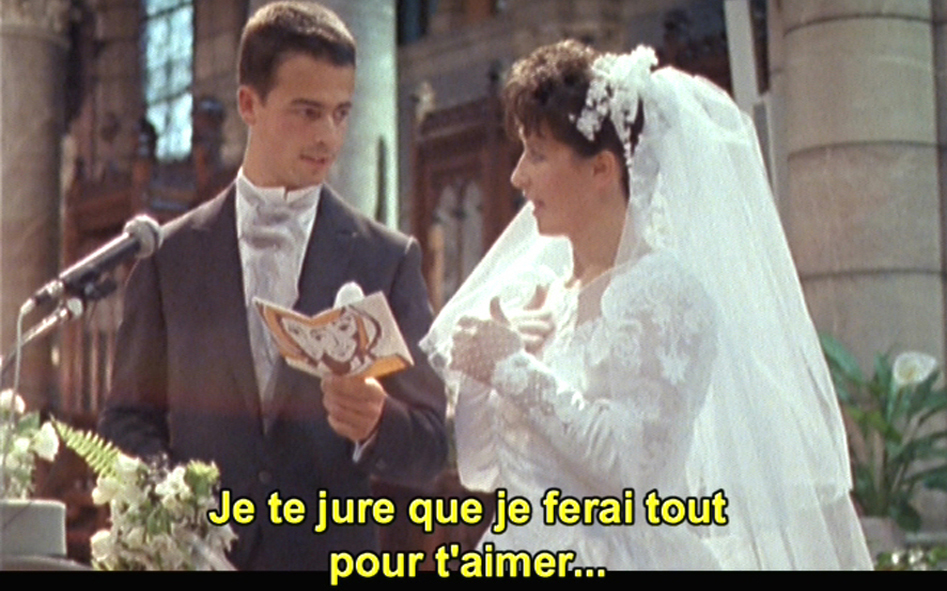

First of all I started by getting deeply involved again in learning sign language, which I had not pursued for years. My assistant did the same thing, and got just as much pleasure from it as I did. This approach was essential because I didn’t want to have to have an interpreter, I really wanted to establish a direct contact with the people. I can’t truthfully say that we became good at signing, but we got by, and it was this that gave us entry all round. Be that as it may, when shooting began, I certainly didn’t have all the characters lined up. The idea to film a marriage came rather late, for example, and what’s more, it took me two months to find the couple in the film. So the characters were chosen little by little as shooting went ahead. There were people who were obvious choices right away, like Jean-Claude Poulain and the school children, and others, like the newlyweds, whom we had to spend a long time looking for. There were others, lastly, like the group of young Americans who ended up in the film more or less by chance.

How was the shooting? What problems did you come up against ?

The filming was spread over a period of about 8 months, with alternating phases of location scouting and preparation. For the first few days I was completely at sea! I was filming situations which I didn’t understand anything about, and it was disastrous. When a deaf person addressed me, it was more or less okay because he would make an effort to “sign” slowly; but I couldn’t decipher the sign language well enough to follow deaf people when they talked with each other, it went much too fast for me. And then because deaf people express themselves through signs, that capsizes all conventions: you can no longer do close-ups or cutaway shots because you risk losing the thread. Among deaf people there is no such thing as a voice-over, there is no off-screen. So we really had to go through a whole learning process to work out what filming methods were suitable, the framing, where to place the camera, and the right distances.

Did you know in advance how the film would be constructed ?

During the filming I gathered a whole lot of material, almost 40 hours of rushes… but in fact it was not until the editing that the film really came together in a concrete way. Needless to say, at the outset I had established one or two narrative principles… but at the same time, I was keen to leave the door open and reserve plenty of room for improvisation and off-the-cuff spontaneity. I hate feeling I’m a prisoner, obliged to confine reality within a discourse that’s been laid down in advance, because reality is always richer than the way we sum it up. I like to tackle things in such a way that the “real” can jostle the way things unfold. Incidentally, there are a few sequences, all the ones where the characters directly address the camera, which I decided to shoot while the film was being edited, at a particular moment when the construction of the film had come up against a brick wall.

So it was during the editing that the film was actually “written” and that we found its narrative form. For me, the editing phase is a bit akin to a slow labour of mourning, during which you have to get rid of and undo the bulk of what has been filmed.

Did you deal with the soundtrack in any special way ?

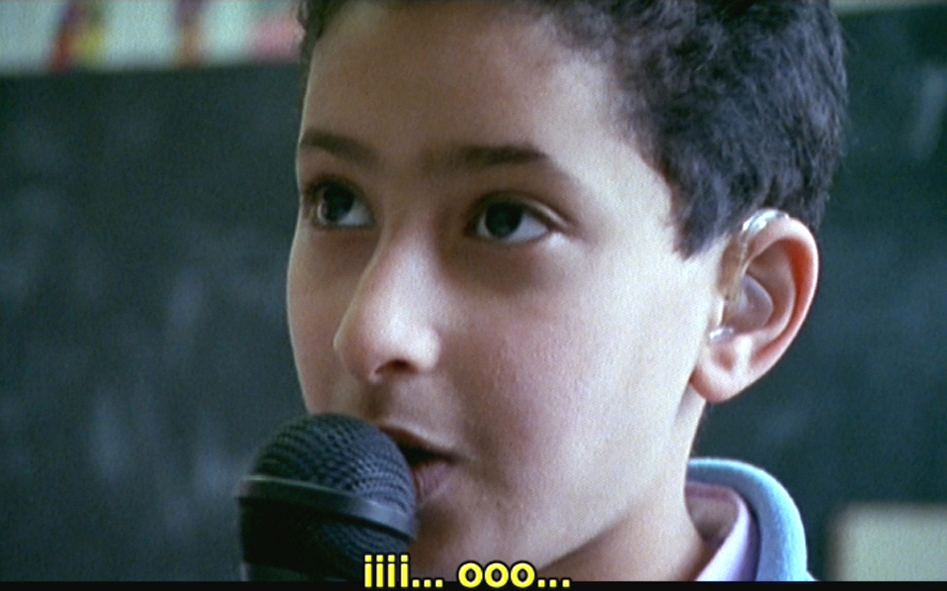

For a long time I clung doggedly to the idea that you could recreate the way deaf people perceive sounds; because even among totally deaf people, there’s rarely such a thing as pure silence; rather you have something far away, and very distorted. In particular I was keen to deal with certain sequences in the school like that, as if reproducing the subjective viewpoint of the children when the schoolmistress asks them to repeat a sentence after her. The viewer can instantly under-stand how difficult it is, because it’s totally abstract, for a completely deaf person to reproduce sounds and master his or her voice. So with the sound engineer and the editor, we went into a hearing aid specialist’s cabin to listen to sounds the way various kinds of deaf people pick them up. Subsequently, during the editing, we started to rework certain sequences based on this particular perception, but it didn’t work. Whatever we did, it came across as a terribly phoney “film effect”, and it wasn’t remotely believable. So I came back to simpler ideas. The ambient sound was often toned down, put at a slight remove, in such a way as to focus the viewer’s attention on the gestures. What’s more, there’s no extra music in the film. The only musical moments tally with scenes in which the music was part of the “live” sound: in the theatre, in the church during the wedding, after the wedding banquet when everybody is dancing, and in the school, when children with normal hearing from a nearby class are singing.

Dossier de presse - 1991

How did you get the idea for the film ?

It’s a story with lots of twists and turns, and its origins go back years! In 1983, I was contacted by a group of psychiatrists to take part in the preparation of an educational film about sign language. As I didn’t know a thing about the world of deaf people, I signed up for a course in sign language which was given by a young teacher who was completely deaf himself. It was a real shock! Up until then I had seen deaf people as handicapped, period. And there I was all of a sudden faced with a man with a quite outstanding wealth of expression, a kind of born actor, capable of conveying all the shades of meaning of a thought just through the movements of his hands and the expressions on his face. For reasons which I don’t recall too clearly, the project put forward by those psychiatrists came to nothing, but for my part I started meeting more and more deaf people and I became really interested in their way of communicating. By discovering the beauty of sign language, the incredible range of its possibilities, and by also discovering the importance of things visual among deaf people, the keenness of the way they look at things, and the extraordinary visual memory they are capable of having, I started to think that a film about deaf people would be a way of “working” the very stuff of film, for the very good reason that it involves a language in which every word and every idea is translated by images drawn in space. So I wrote a fictional screenplay, but after various ups and downs, I didn’t manage to find the funding for it, and in the end I moved on to other things… But in 1991, the idea resurfaced, this time no longer in the form of a fiction film, but as a documentary, or, let’s say… a film that would tell true stories, with real characters.

What were the basic choices that steered your work ?

My idea was to make a film that would abruptly plunge the viewer into the world of deaf people, a film whose mother tongue would be sign language. If I can so put it, I wanted to let those people about whom we know nothing speak for themselves, people who have a totally different communication system from ours. My intent was to try and look at the world through their eyes. Over and above the “handicap” issue, what the film emphasizes is the existence of a real deaf culture, which has its own roots, its codes, its models, and its customs. I wanted to confront the viewer with that particular culture, not in an abstract or theoretical way, but by following various characters and telling their story. So, without any exceptions, the characters are people who are completely deaf, born deaf, or people who became deaf during the early months of their lives, in other words before they acquired language. I decided not to include “hearing-impaired people”, even though there are more of them, but this is a film, not a statistical survey! The challenge and the wager involved moving to the other side, and setting out to discover that distant “land” where seeing is of considerable importance.

How did you set about meeting the characters in the film ?

First of all I started by getting deeply involved again in learning sign language, which I had not pursued for years. My assistant did the same thing, and got just as much pleasure from it as I did. This approach was essential because I didn’t want to have to have an interpreter, I really wanted to establish a direct contact with the people. I can’t truthfully say that we became good at signing, but we got by, and it was this that gave us entry all round. Be that as it may, when shooting began, I certainly didn’t have all the characters lined up. The idea to film a marriage came rather late, for example, and what’s more, it took me two months to find the couple in the film. So the characters were chosen little by little as shooting went ahead. There were people who were obvious choices right away, like Jean-Claude Poulain and the school children, and others, like the newlyweds, whom we had to spend a long time looking for. There were others, lastly, like the group of young Americans who ended up in the film more or less by chance.

How was the shooting? What problems did you come up against ?

The filming was spread over a period of about 8 months, with alternating phases of location scouting and preparation. For the first few days I was completely at sea! I was filming situations which I didn’t understand anything about, and it was disastrous. When a deaf person addressed me, it was more or less okay because he would make an effort to “sign” slowly; but I couldn’t decipher the sign language well enough to follow deaf people when they talked with each other, it went much too fast for me. And then because deaf people express themselves through signs, that capsizes all conventions: you can no longer do close-ups or cutaway shots because you risk losing the thread. Among deaf people there is no such thing as a voice-over, there is no off-screen. So we really had to go through a whole learning process to work out what filming methods were suitable, the framing, where to place the camera, and the right distances.

Did you know in advance how the film would be constructed ?

During the filming I gathered a whole lot of material, almost 40 hours of rushes… but in fact it was not until the editing that the film really came together in a concrete way. Needless to say, at the outset I had established one or two narrative principles… but at the same time, I was keen to leave the door open and reserve plenty of room for improvisation and off-the-cuff spontaneity. I hate feeling I’m a prisoner, obliged to confine reality within a discourse that’s been laid down in advance, because reality is always richer than the way we sum it up. I like to tackle things in such a way that the “real” can jostle the way things unfold. Incidentally, there are a few sequences, all the ones where the characters directly address the camera, which I decided to shoot while the film was being edited, at a particular moment when the construction of the film had come up against a brick wall.

So it was during the editing that the film was actually “written” and that we found its narrative form. For me, the editing phase is a bit akin to a slow labour of mourning, during which you have to get rid of and undo the bulk of what has been filmed.

Did you deal with the soundtrack in any special way ?

For a long time I clung doggedly to the idea that you could recreate the way deaf people perceive sounds; because even among totally deaf people, there’s rarely such a thing as pure silence; rather you have something far away, and very distorted. In particular I was keen to deal with certain sequences in the school like that, as if reproducing the subjective viewpoint of the children when the schoolmistress asks them to repeat a sentence after her. The viewer can instantly under-stand how difficult it is, because it’s totally abstract, for a completely deaf person to reproduce sounds and master his or her voice. So with the sound engineer and the editor, we went into a hearing aid specialist’s cabin to listen to sounds the way various kinds of deaf people pick them up. Subsequently, during the editing, we started to rework certain sequences based on this particular perception, but it didn’t work. Whatever we did, it came across as a terribly phoney “film effect”, and it wasn’t remotely believable. So I came back to simpler ideas. The ambient sound was often toned down, put at a slight remove, in such a way as to focus the viewer’s attention on the gestures. What’s more, there’s no extra music in the film. The only musical moments tally with scenes in which the music was part of the “live” sound: in the theatre, in the church during the wedding, after the wedding banquet when everybody is dancing, and in the school, when children with normal hearing from a nearby class are singing.

Libération - 14 août 1992

Whether it’s in French ( Le Pays des sourds ) or in English ( In the Land of the Deaf ), the title of Nicolas Philibert’s 1992 documentary faintly suggests something ethnographic and exotic, like the 1914 In the Land of Head-Hunters (subsequently and more tactfully re-edited to yield the 1973 In the Land of the War Canoes). Given the dominant discourse that it’s coming from, this also implies something colonialist—-a view from a ruling and dominant power of a contained underclass. But it is part of the film’s special achievement and the world it opens up to make us feel by the end that Dorothy in the Land of Oz might be a more appropriate cross-reference, with Philibert and the spectator jointly taking on the role of Dorothy. The difference is that the land he’s showing is real as well as magical and other-worldly.

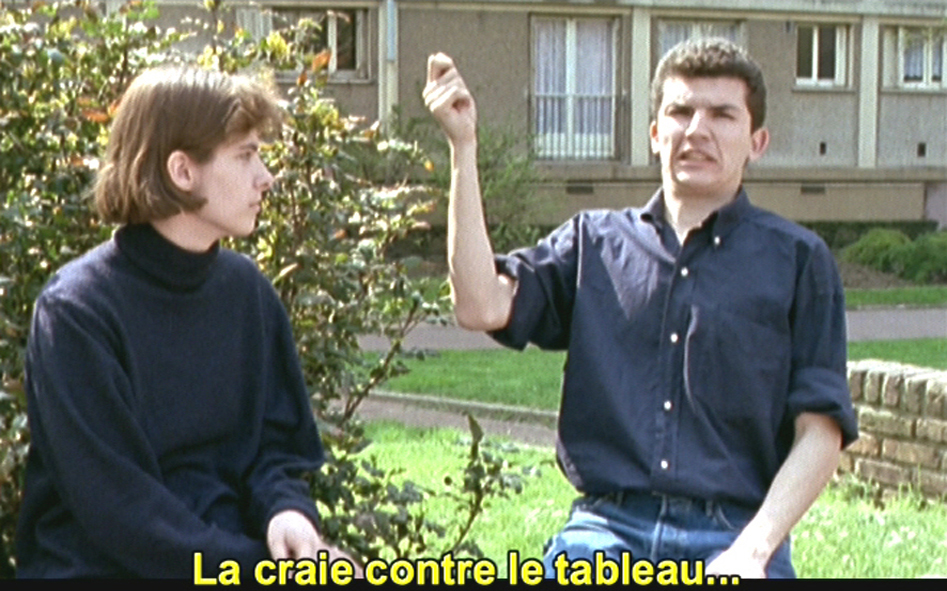

The film implicitly reflects on three different kinds of language–the different languages spoken in movies, the so-called language of cinema, and Sign, specifically the language of the deaf. Different languages are suggested by the use of subtitles in the film to translate Sign as well as vocal speech. But then Jean-Claude Poulain–the most expressive purveyor of Sign in the film, who also teaches that language—-explains that Sign is less of a universal language than we suppose, because it is articulated somewhat differently in each country. He adds, however, that it takes him only a few days to pick up Sign in another country, which finally suggests that it’s still more universal than spoken languages.

What’s usually meant by “the language of film” is the set of visual and aural conventions involving editing, framing, mise en scène, and sound to which all moviegoers respond, though few commentators have bothered to spell them out. Whether these conventions and the messages they send constitute a language is debatable, though there was an entire cottage industry of film theory during the 70s predicated on that assumption. The intricate rules of conventional editing are a good example of what I mean: very few viewers are capable of defining them but nearly everyone responds to them, just as native speakers of a language follow the rules of grammar even if they don’t consciously know what they are.

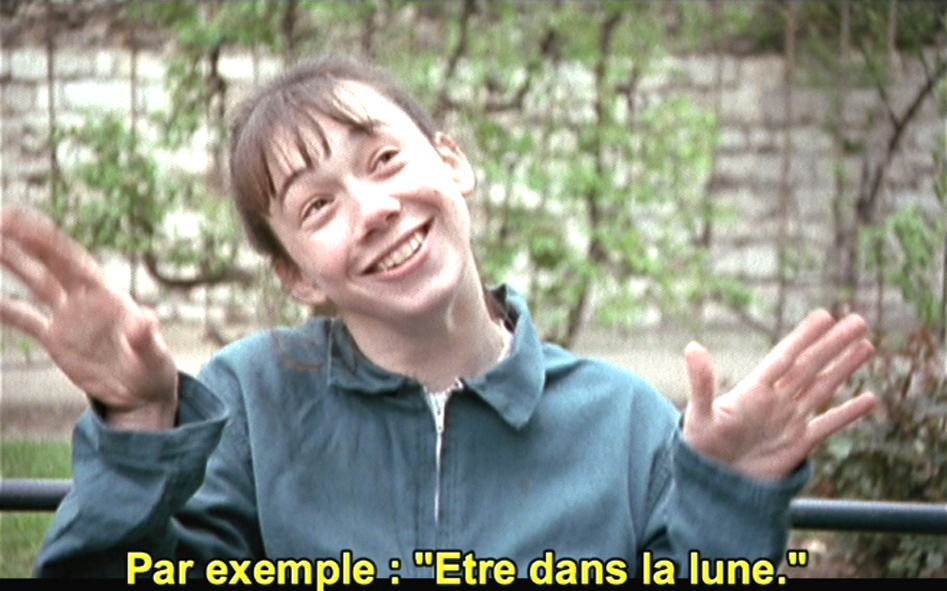

It seems that the usual response of someone who hears a foreign language is to assume, often unconsciously, that it’s a failed attempt at the language one already knows–an assumption subtitling helps to encourage by supposedly providing the “real” meaning. Similarly, when most of us first encounter Sign, our likely first response is to “read” it as if it were a form of pantomime. But according to Oliver Sacks in his book Seeing Voices: A Journey into the World of the Deaf (1989), this reflects a misconception: “We see…in Sign, at every level–lexical, grammatical, syntactic–a linguistic use of space: a use that is amazingly complex, for much of what occurs linearly, sequentially, temporally in speech, becomes simultaneous, concurrent, multileveled in Sign. The “surface’ of Sign may appear simple to the eye, like that of gesture or mime, but one soon finds that this is an illusion, and what looks so simple is extraordinarily complex and consists of innumerable spatial patterns nested, three-dimensionally, in each other.”

This observation can be adapted to the so-called language of cinema: young viewers often maintain that silent films are unwatchable today, that they’re crude, primitive approximations of what sound movies do much better. But this rejection is of course partially a learned response rather than an innate reaction: the same audience never seems to mind the visual corruptions and limitations of TV and video. One might come closer to the truth by reversing the paradigm: isolating certain silent masterpieces and assuming that current popular sound movies are crude attempts to approximate their expressiveness. Compare Tom Hanks or Woody Allen with Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Stan Laurel, Harry Langdon, or Harold Lloyd and the difference is like that between an able conservatory pupil playing an exercise and a virtuoso musician performing in concert.

Better yet, compare the expressiveness of a Bruce Willis or a Jean-Claude Van Damme or an Arnold Schwarzenegger (especially in his pre-political mode) with that of any of the people speaking Sign in Philibert’s documentary, children or adults, male or female, and the differences become astronomical. Despite the benefit of spoken language, these action heroes’ palettes are so limited that the only “emotions” they register are actually parodies of emotions. By contrast the people signing in Philibert’s film–and these are almost the only people we see–use their faces and bodies like agile paintbrushes, speaking to us and to each other with all the colors imaginable, vibrantly and directly. (As Jean Gremion writes in his book The Planet of the Deaf [1991] “In sign language, the smallest bat of an eyelash can become an element of syntax.”)

One might also regard the subtitles in Philibert’s film the way one regards librettos, as texts without the benefit of either music or performance, which is what the deaf people are supplying. One suspects that Philibert has this analogy in mind, because he begins the film with the camera pulling back from two women and two men performing Sign together to sheet music on music stands, and the musical effect of their individual and collective gestures –their passages in unison and their interactive duets–is immediately obvious.

Even more remarkable, the fact that most of us in the audience understand English but not Sign plays a secondary role. English subtitles translate for us, but one discovers early on that, like subtitles translating spoken languages, the translation is only a partial, reductive version of what’s being expressed. Even if one ignores the subtitles, the range of emotions–from grief to joy, from anger to affection, from enthusiasm to indifference–is so great, and the power behind each of them so immediate, that we often feel blown away by the sheer force of the subjects’ personalities. The particulars conveyed in the subtitles are helpful and important, but as the film progresses they begin to seem more and more like footnotes to large-scale texts that only Sign can convey.

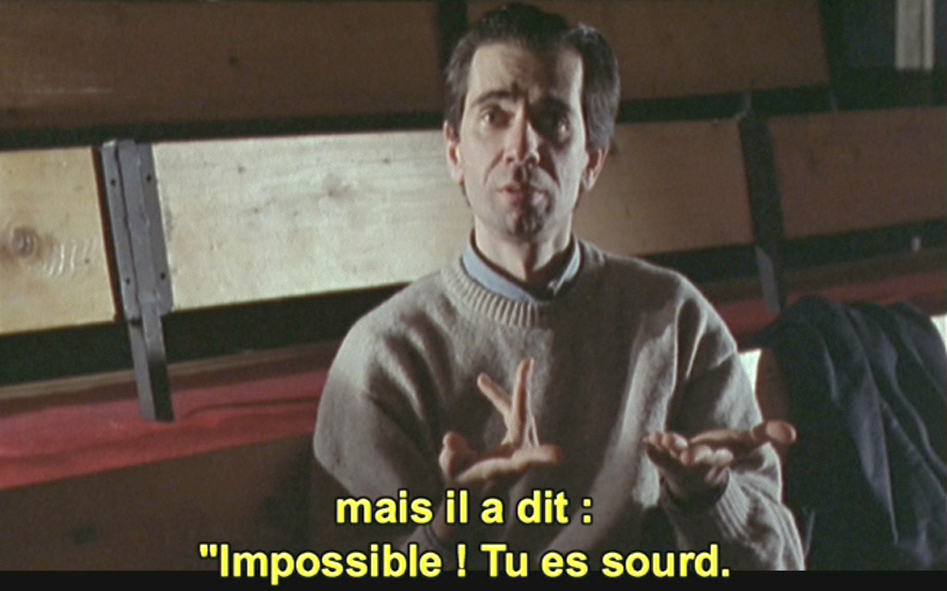

The relationships between Sign and cinema are obviously deep and complex; significantly, the film’s first Sign monologue reveals a mute subject’s lifelong fascination with movies and his early desire to become a film actor, until a director neighbour informed him that this was impossible. But this doesn’t mean that Sign and cinema are automatically interchangeable. The aim and achievement of Philibert’s film is to plunge us as completely as possible into the world of communication between deaf people, and in order to do this he’s had to rethink, to some extent, the language of cinema–the conventions of framing, editing, and even sound recording. In a fascinating article for the French film magazine Trafic (no. 8, automne 1993), Philibert has described in detail how conventional documentary filming methods proved inadequate for capturing the subtle interactions between deaf people. (For example, “Although sound operates in 360 degrees, in the realm of the deaf the voice-off does not exist: out of sight, communication is not possible; outside the frame, not even a hello.”) In the same article he explains why making a purely silent film would not have accurately represented the world of the deaf–which, “contrary to what is believed, is not pure silence. Confused, faraway murmurs, diffuse noises: even for the so-called “stone’ deaf, it is not nothingness.” Philibert manipulates his own sound track at times in order to suggest some of that subjective experience—-a technique that becomes especially apparent towards the end of the film–and some of the Sign monologues deal with certain aspects of the experience as well. (A mute born into a nearly all-deaf family describes the initial experience of using a hearing aid as extremely unpleasant: “The sound of chairs–it was awful.”)

But the principal bounty of this film is the relatively unmediated and magnificent spectacle of Sign itself, performed by numerous individuals for whom “acting” and “being” appear to be indistinguishable. These extraordinary people include some of the best French child “performers” encountered and seen since the films of Truffaut, as well as the aforementioned Poulain, whose everyday utterances and expressive gestures automatically place him in the pantheon of character actors occupied by such figures as Walter Brennan, Marcel Dalio, William Demarest, and Michel Simon.

I’m tempted to say that I haven’t seen such emotional, multifaceted physical expressiveness in so many people since the golden age of silent cinema; but alas, among contemporary moviegoers that no longer serves as much of a recommendation. So let me put it differently: if you want to see and hear people who will make you feel more alive, the likes of whom you won’t come close to finding in many current commercial releases, check out Nicolas Philibert’s In the Land of the Deaf.

The Boston Globe - November 3, 1994

“In the Land of the Deaf” is disarmingly casual for a film that is so uniquely powerful. Here is a film that, over the course of 99 minutes, will challenge every preconception the viewer may have had about deaf people. Because, in the tradition of ethnographic film but without any heavy‑handedness, In the Land of the Deaf shows a distinct, stillevolving culture that exists among deaf people, most effectively displayed through the richness of sign language.

Rather than calling to mind previous documentaries, Nicolas Philibert’s film seems to continue the French humanistic tradition of Jean Renoir and Francois Truffaut. The scenes of deaf children and their teacher may recall Truffaut’s The Wild Child with one big difference: While the aim in that film was to assimilate the boy into French society, this film celebrates what could be called deaf chauvinism. Its adult subjects, for the most part, prefer to be amon

The Washington Post - October 7, 1994

Nicolas Philibert’s award‑winning French documentary In the Land of the Deaf does much to dissolve borders of ignorance that keep the hearing from appreciating the culture and the language of a constituency (130 million strong worldwide) that might be more easily recognized if it were ethnically or racially defined, or perhaps had its own cuisine.

But this sensitive documentary makes it clear that the deaf are, in all but one sense, no different from any other group, embracing the same range of personalities, sharing the same dreams, experiencing the same emotions. Like any group with a crucial commonality, the deaf are also unique.

Philibert approaches their world in a surprisingly sensible manner, letting his subjects sign for themselves. There is no intrusive narration and no heavyhanded polemic, just the observed expression of children learning to speak, a young couple getting married and a marvelous teacher of sign language with time and memories on his hands.

Jean‑Claude Poulain, who teaches sign language to hearing adults, provides both historical context and insights into complexities of deaf culture. The fiftyish Poulain recalls that when he was a child, his hands were tied behind his back in an effort to make him talk; now Poulain is a quiet crusader in the deaf‑rights movement, pushing for bilingual education (French/sign). Blessed with a poignant Jacques Tati face that reflects immense passion and pathos, Poulain is a story‑signer of the highest order. At one point, referring to his hearing daughter, he confesses, “I had dreamt of having a deaf child ‑ communication would be easier. But I love her all the same.”

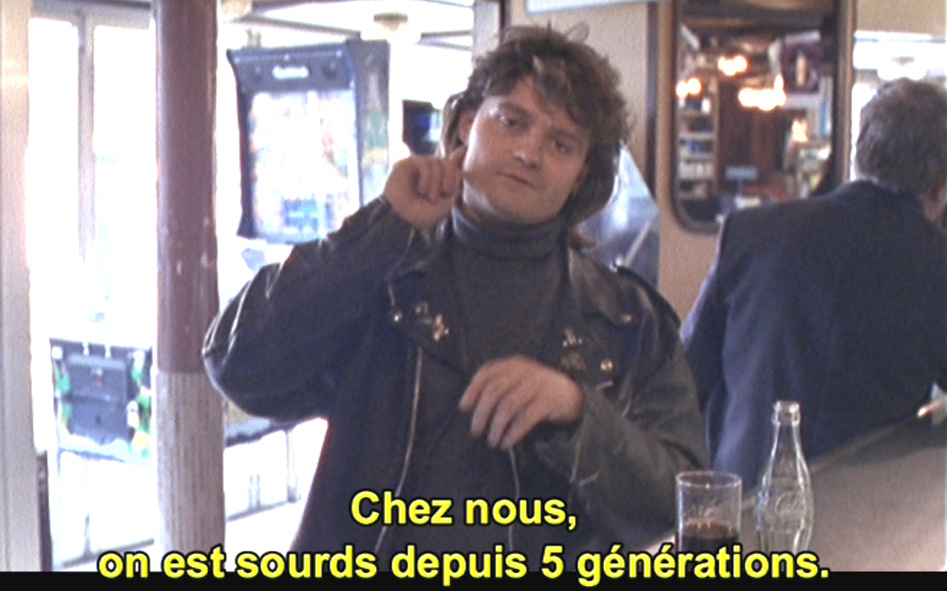

Offhanded but revealing, that twist is repeated later when a young man in a bar signs family history, noting that he comes from five deaf generations that have included the occasional hearing child (“poor thing”). The more common situation of deaf children born into hearing families is revealed in the recollections of several college‑age kids who grew up feeling excluded.

But Philibert (who is not deaf) is not out to demonize the hearing. The only villain here is ignorance. Philibert suggests the complexities of both emotions and politics in the world of the deaf, and some of the film’s most poignant moments capture the interaction of teachers and youngsters struggling patiently to create public sound out of private silence.

All the kids are engaging, but one in particular, 6‑year‑old Florent, is a genuine heartbreaker. Blessed with huge, inquisitive eyes, Florent is first seen struggling with a tear‑drenched writing assignment; at film’s end, though, he’s revealed as a playful, loving and loudly mischievous child, dealing with his condition, not burdened by it. “I look so I can hear,” Florent explains, and you understand why he’s been blessed with those eyes.

The importance of sight and sightlines is apparent. After all, sign language is a matter of hand‑eye cooperation. Every gesture tells a story, and Philibert captures the rush of signs, the liquid loquaciousness of chattering hands, the body French of subjects whose mode of expression is as varied, lively, intense, rich and witty as any with sound attached.

And, Poulain explains, there’s a practical edge to consider: There may be different dialects of sign language around the world ‑ he signs specific examples ‑ but common grounds allow for quicker communion than might be possible for the hearing, with their disparate languages. In this documentary, there is sign language, spoken French and English subtitles that cover the first two elements. And gradually, it is the sign language that comes to seem clearest, demystified by Philibert’s respectful attention and empathy.

There’s one other charming tableau involving a young deaf couple, Hubert and Marie‑Helene (95 percent of the deaf marry within the culture). Philibert captures their wedding, where natural nervousness is heightened by the challenge of an essentially literary ritual, and later includes their apartment search (made difficult because of intense communication problems with a landlord) and the arrival of a baby. But the traditions and centeredness of the deaf community are most apparent in a scene from the wedding party, which includes both deaf and hearing folk, and features loud music and dancing. At one point the music stops, but Hubert and Marie‑Helene keep on dancing, secure in themselves and their silent world.

L.A. Village View - January 20, 1995

Strange as it may sound, learning to take some things for granted is an essential aspect of growing up. Without the ability to ignore certain stimuli, a person would surely be driven mad by the sensory overload caused by society’s neverending barrage of sounds, sights, and smells. Most people don’t often think about their sensual capabilities, and why should they ? Our senses are taken for granted, like the stars and the streets.

It is a testament, then, to Nicolas Philibert that his documentary In the Land of Deaf will undoubtedly continue to affect many filmgoers long after they exit the theater. This film leaves one with an added appreciation for the ways in which most of us have only glimpsed in passing : that of people whose lives are conducted in silence.

To say that In the Land of Deaf is fascinating does not do it justice. For not only does the film shatter a number of preconceptions most hearing people harbor about the deaf, it does so without a hint of pity or condescension, and introduces a captivating cast of characters in the process. Chief among these people is sign-language teacher Jean-Claude Poulain, an extraordinarily expressive man whose enthusiasm is infectious. Among the things we learn from Poulain is that, contrary to popular belief, sign language is not international ; learning new languages, however, is easier for the deaf, he explains, and usually takes only a matter of days.

Other revelations await. After opening with a quartet of signers performing a poem in concert, the film unveils more surprises the degree of idiosyncrasy in signed speech ; the fact that signers are rechristened by their peers, their new names usually derived from a physical characteristic (the teacher’s name in sign, for example, translates as « skinny »). Perhaps most striking though is the extent to wich personal reality is shaped by perceptionone young man recalls being sure that he could become a movie actor because he assumed that all actors, were miming anyway, while a woman recalls that as a child, she never saw any deaf adults at her school, leading her to wonder, « Do we all die at 20 ? »

The movie has no real narrative drive : Philibert’s style might be called laissez-faire filmmaking. He has simply photographed the lives of a variety of deaf people and combined the edited results. And yet his decisionmaking is fawless : he shoots almost axclusively from a medium distance, knowing well that seeing these poetic hands in action supersedes the need for closeups, and refains ambient sound throughout, avoiding the obvious gimmick of forcing the audience to share in the silence of his subjects. He has the confidence to be unobtrusive, allowing viewers to marvel at the moments he has collected—the computer game in wich players progress through a maze by correctly pronouncing vowel sounds into a micrphone ; the warmth and support these students show a crying classmate ; the joy on the faces of the revelers at a deaf couple’s wedding. And most of all, he allows the audience to drink in the grace and g-beauty of sign language itself.

The best documentaries are not agitprop but exploration. They do not tell but show, and it would be hard to find a more successful example of the form than the masterful In the Land of Deaf.

Deaf Life - November 1994

After its American debut at the 1994 San Francisco Film Festival, Nicolas Philibert’s French documentary In the Land of the Deaf netted the Golden Gate Award and glowing reviews that described the movie as “a warm, engrossing, eye‑opening experience” (New York Times), “completely inspiring” (Variety), and “seductive and magical” (Siskel & Ebert).

Most — if not all —of these reviews came from hearing critics whose exposure to deafness was probably limited to movies like “Children of a Lesser God”, “Johnny Belinda”, and “The Miracle Worker”. Furthermore, the film won a slew of awards on its way along the film‑festival circuit: Grand Prize, Bombay International Film Festival 1993; Grand Prize for Documentaries, Vancouver International Film Festival 1993; Prize for Best Documentary, Vallodolid Film Festival 1993; Prix Humanum 1993, Belgian Film Critics’ Association, for “a film which defends a society in which different peoples and cultures can cohabit”; and Grand Prize, Belfort Film Festival 1992. We know that hearing people’s views of us — the signing and culturally deaf —can differ drastically from the way we view ourselves, so naturally I wanted to see the film for myself. (Because the film deals with both signing Deaf adults and deaf children who are learning to speak, the non‑capitalized word “deaf” is primarily used in this article.)

The documentary In the Land of the Deaf is very straightforward. It does not attempt to preach, or take sides on why or how the deaf community should be changed. This is truly admirable, because once a person studies deaf culture and sign language, it is very difficult to stay neutral in deafness‑related issues such as the cochlear implant, the use of hearing actors in deaf roles, and so on. Most film documentaries tend to be edited to present, if not prove, a particular point of view about an issue, in the same way that a book like Thomas and James Spradley’s “Deaf Like Me” was written to encourage hearing parents to use sign language with their children, or Henry Kisor’s “What’s That Pig Outdoors?” advocates oralism over sign language.

In the Land of the Deaf differs in other ways as well. Philibert asks us —hearing audience members, especially —to look at deaf people in a different light. Instead of stringing together scenes to tell a story from beginning to end, he asks us to observe deaf children struggling to speak; we attend a deaf couple’s wedding, and go with them as they try to find their first apartment together; we watch an older deaf man teaching French Sign Language classes. Philibert’s choice of cinema verité — a technique of filming unrehearsed live scenes and then letting the pieces come together in the editing room — and the few pieces I’d read about him made it clear that, unlike most hearing filmmakers interested in deafness, Philibert had truly done his homework.

In 1983 Philibert enrolled in a sign‑language course to prepare himself for making a film that had been commissioned to teach hearing parents of deaf children how to sign. That film did not materialize, but Philibert did write about his experiences in making In the Land of the Deaf in Trafic, a French cultural journal. (His quotes are translated from French into English, and some are paraphrased for clarity.)

“ From the first day, our teacher, a profoundly deaf man who only spoke in sign, pulled a series of drawings from his satchel. They were intended to make us understand, in terms of framing, the space which was appropriate for the practice of his language. Not only would our signs require the greatest precision, but moreover, they could not be too small or too large, so as to be inscribed within a space corresponding quite exactly to that which filmmakers would call a medium tight shot. But there would also be some signs that would have to be executed in close‑up, and still others, even including zooms! This allusion to the language of cinema… affected me like an electric shock..

(…)

While filming signers, I discovered that I couldn’t expect to frame them from a wide variety of angles as one could with hearing speakers. Although sign operates in 360 degrees, in the realm of the Deaf the “voiceoff” does not exist. Out of sight, communication is not possible; outside the frame, not even a hello …. I cannot forget that day in April 1991 when, in a [schoolyard], we tried… to capture the spontaneous conversation of a small group of adolescents. The camera operator, camera on his shoulder, was moving among them, panning intuitively from one to another in the hope of arriving at the right moment on the one who was expressing herself. Standing back a little, I observed the entire scene, the sound engineer walking with his [microphone] perch, attentive to the slightest sounds [the Deaf adolescents] allowed to escape, the camera operator making his best effort, the girls chatting …. Suddenly, I understood that the vague sounds they emitted while signing, these hoots, those little cries, the tapping of fingers, the rustle of their clothes, were not distinct enough for the camera operator to follow their movements by ear as if he were in the middle of a group of hearing persons. Not being able either to hear this silent conversation or see the entire group through the camera, he worked blindly, without ever knowing where the next answer was going to come from. So I stood next to him, holding him by the shoulders, and I… guided his movements, at least having the advantage of being able to look in all directions. The results were just as [bad because] I couldn’t anticipate who was going to sign next; it never failed that she had started to sign by the time the camera reached her. A few fractions of a second late on our ‘characters,’ we.. . missed the beginning of each sentence, even when we did not miss the whole thing completely. The conversation was much too fast.

So we decided… to enlarge the frame. At least the whole group would be under control. We moved back a few steps. Although one of them had her back to us, and two or three others were in profile, I hoped to be able [to figure out their dialogue], thanks to the answers which were the most legible… [As it turned out, I had to ask] the participants to see the sequence, I hired a professional interpreter, and I ran the scene on the editing table a hundred times, but the sequence was unreadable.

(…)

The idea of a silent film … was thrown away from the start. It was necessary that a film about the deaf be a sound film [to emphasize] that the world of the Deaf, contrary to what is believed, is not pure silence. I discovered that it was best to avoid any and all sound processing or artifice which would detract attention from the signs… and keep oneself to simplicity and transparency of direct sound. In other words, the hearing viewers should soon forget that they are hearing sounds while watching the film.

(…)

While subtitling the film, I realized that subtitles could not always appear simultaneously with signs themselves, for both could not be read at the same time. I decided that placed slightly ahead of the signs, the subtitles would permit the viewer to identify some of [the signs], to “recognize” after the fact …. [It became] a game of guessing the meaning of the signs before getting the translation.

When I learned that Nicolas Philibert would be in the States briefly to accept the National Council on Communicative Disorders’ Stephanie Beacham Award in Washington, D.C. for his work on “In the Land of the Deaf”, I interviewed him by fax at International Film Circuit in New York City, the U.S. distributor of his film.

Have you had deaf people object to the fact that you —a hearing filmmaker —have made this documentary about them?

No, I have never had a deaf viewer object because I’ve never tried to pretend that I could have a deaf person’s point of view. All the deaf viewers have understood that. For sure, a deaf person would have made a different film.

Do you feel that because you were hearing, it took you a long time to find the “right” people to appear in the film?

From the very beginning, I worked with deaf people and quickly we became good friends. They advised me and helped me network in the deaf community. But, at the same time, they did not try to impose their point of view on me. They respected all my choices because the film is clearly my point of view. I wanted to show the complexity of real life, and so I chose people of different ages and social conditions, deaf of deaf parents and deaf of hearing parents, and the oral educational system which is unfortunately still so dominant in France today. I wanted to show the difficult conditions into which the deaf are thrust —how difficult it is to be a deaf person in the world of the hearing.

Did you have to rehearse any of the participants prior to filming?

All the scenes were shot live and unrehearsed—with the agreement of the people being filmed—except the interviews.

It’s clear that you wanted to make the film accessible to the deaf, yet when I watched it, I noticed that most of the sounds generated in speech‑therapy lessons or in the song that hearing children sang in the beginning of the film were not subtitled. Because I don’t know French, I couldn’t tell if the child was practicing a vowel or a word. Why wasn’t all of that subtitled?

When the children sing, they are too far away from the microphone, so we cannot understand the words they are singing. That is not subtitled. When they are in the classroom, almost everything is subtitled. Whenever you add subtitles, it is necessary to condense. In the same way, when people are signing in the film, I could not translate every sign. I had to condense for reasons of space and time.

In the wedding scene between a deaf couple, I noticed that the minister was hearing. I was very surprised because I expected to see a deaf minister involved in such a ceremony. In France, aren’t deaf people encouraged to go into the ministry to help other deaf people?

What you have to know is that the situation for the deaf in Europe is probably much more difficult than it is in the United States. In Europe, deaf people are still considered “those poor handicapped,” and we don’t give them access to the education they need to become [holders of] professional jobs—like a minister or a teacher or an engineer. They are kept doing manual sorts of labor, even if their intellectual capacity should allow them to do more. So there are no deaf ministers in France at this time.

During the wedding, they didn’t even have an interpreter, and this was disastrous for the couple. In all of France, there are no more than fifty sign‑language interpreters. It’s a catastrophe. I kept this scene in the film because it is meant to underline this very problem. The scene involving the deaf couple’s apartment search also shows the everyday difficulties of deaf people living amidst hearing people. Maybe the scene also shows how hearing people are lost the first time they find themselves face‑to‑face with a deaf person. For most hearing viewers, the rental agent looks more “handicapped” than the couple and their friend.

What is the most important thing you’ve learned from the making of this film?

I’ve discovered the richness of deaf culture. And working with deaf people for the film, I was able to develop my own visual acuity.

About the author: Raymond Luczak’s Notes of a Deaf Gay Writer (originally published in Christopher Street) appeared in our March and April 1991 issues. He also edited Eyes of Desire: A Deaf Gay and Lesbian Reader (Alyson Publications, 1993).

Libération - March 4, 1993

Having set off to discover the Land of the Deaf, Nicolas Philibert returns with a story full of strange characters who do not speak but “sign”. A language whose grammar and rules are close to those of film.

Films rarely have a meaning. Nicolas Philibert’s Le Pays des sourds (In the Land of the Deaf) has the rare privilege of having found its meaning along the way, according to a fine principle of moral justice dictating that, having set off without luggage but with a great deal of love and curiosity for the land of those who cannot hear anything, the filmmaker has returned enriched with an extraordinary story. Not a particularly simple story but a very touching one, full of strange and powerful characters, on whom the virtuoso gestures of their language confer a sort of occult power.

All these adults speak and all these children are learning to speak, but with signs, according to the codes of a language put together since the dawn of time. With lively and magical gestures, a few snatches of which we instinctively comprehend but that which speakers and hearers are cut off from most of the time. However, we can tell that it would not take much of an effort from either side to meet up, for what Nicolas Philibert discovers, as we do along with him, from the first steps of his journey, his magnificent intuition, is that sign language is a language close to the cinema and that its grammar and laws belong to a related line. Not only because we can trust the deaf to be especially attentive to images but, above all, as the linguist William C. Stokoe writes, “This language continually shifts from normal vision to close-up, then to the medium shot and once again to the close-up, exactly in the same way that a film editor works… Not only does the disposition of the signs call to mind an edited film more than a written narration, but each ‘signer’ is positioned like a camera.” (1).

In opening up this theoretical abyss almost inadvertently, Philibert nonetheless enters with measured steps, with desire, caution and reflection, especially as all the fairy godmothers of the cinematic language can legitimately be summoned to this summit meeting. We can thus imagine that, with such ideas in mind, the director has set his ambitions very high. This vision of sign language as a human and incarnate metaphor for the cinema will naturally lead him to use all the resources at his disposal to feed it.

Having enrolled, for the film’s requirements, in a beginners’ sign language class, Philibert first of all discovers that his teacher, totally deaf, uses drawings similar to those of a storyboard as an educational tool designed to get across, in terms of framing, the space that is suited to this language. “Not only does signing demand extreme precision, but it mustn’t be too constrained or too ample so as to find its place in a space that corresponds exactly to what filmmakers around the world call a medium close shot. But there are also signs that have to be made in close-up and others that even include zoom movements.”

Similarly, we need to point out the crucial importance of light in the lives of the deaf since darkness or shadows deprive them of all possibility of expressing themselves. In the same way, for the deaf, there cannot be any voice-over or off-screen action, so there is no possibility of filming them in close-up or slipping in matching shots as this could break the thread of their speech. Forced to invent new filming methods to adapt to his subject, Philibert seizes this opportunity to work on the very matter of cinema. Inevitably, Philibert reached this point too: “Of course, a film like this could not ignore the question of sound. It was inherent in the subject itself. But, for a very long time, I was barking up the wrong tree, obstinately attempting to reproduce the way in which the deaf perceive sound. It didn’t work. So I returned to simple ideas.” Ideas that we see at work in the film, in all their clear self-evidence, ideas literally unheard of before.

But, however elevated the nature of his project, Philibert never pretends to dominate it. What he offers is, in a way, a gift of gratitude to match the welcome that he was given in the land of the deaf. Rather than build for his hosts an umpteenth little socio-documentary chapel, he opens the portals of cinema’s cathedral for them, making a film not about them but for them and everyone, even if it is more often than not generously subtitled for the deaf. A film that seizes the opportunity for the cinema to talk about the deaf and vice versa. A film rich with a thousand nuggets of useful information on deaf culture in which the “non-hearers” do not hesitate to reveal to “hearers” a few of the considerable advantages of their lot: the universality of communication (“In two days, I can talk with a deaf Chinese person.”), the extreme acuity of their gaze and, last of all, the “secret society” dimension of this language that allows them to talk without the non-deaf realizing, right in front of them.

With hands or with words, the movie tom-toms have to sound out for In the Land of the Deaf. You can also combine the two: cross your fingers while wishing that word-of-mouth will work perfectly.

(1) Quoted by Oliver Sacks in Seeing Voices, 1989.