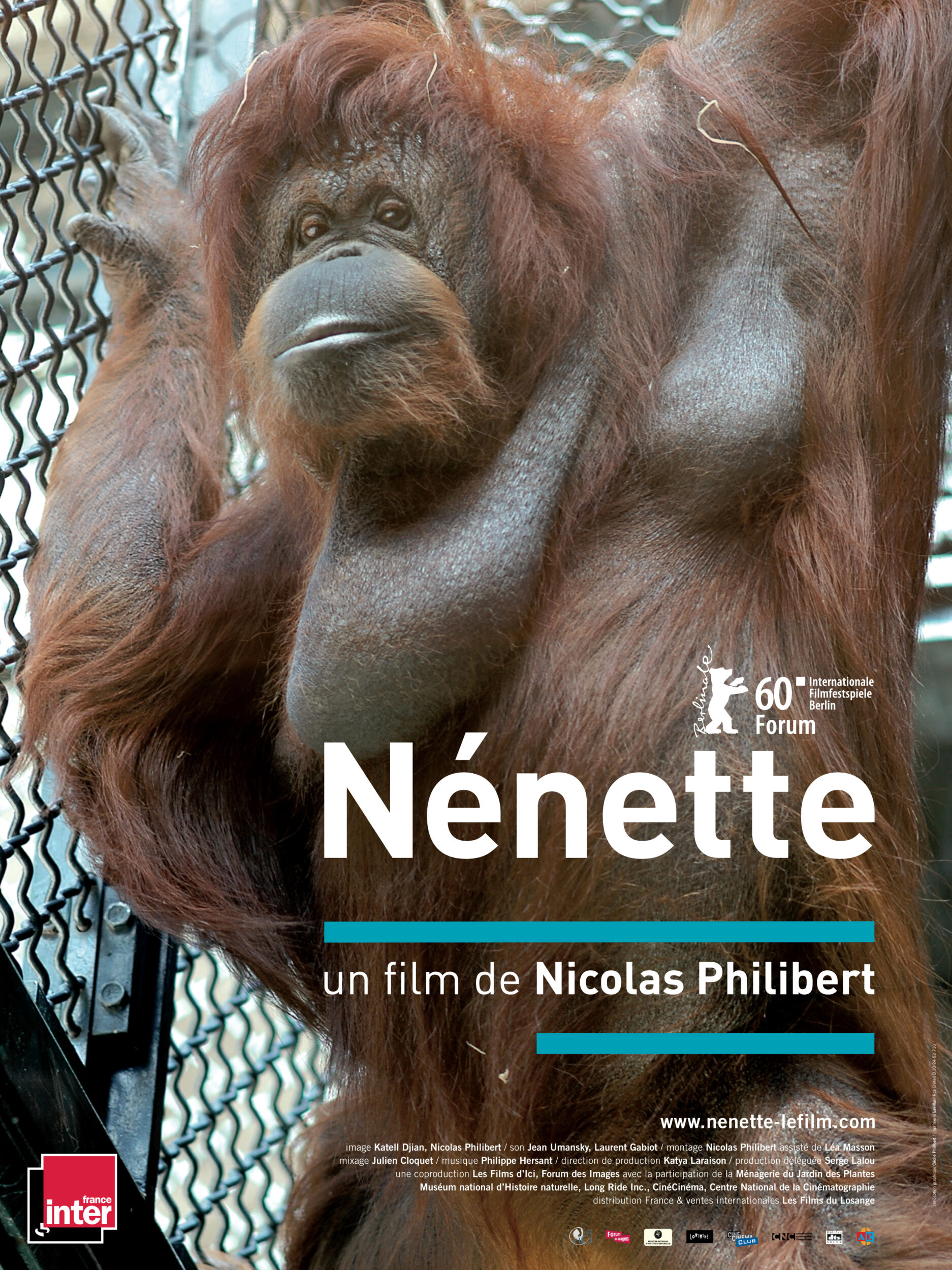

Born in 1969 in the forests of Borneo, Nénette has just turned 40. It is rare for an orang-utan to reach such a venerable age! A resident of the menagerie at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris since 1972, she spent more time there than any member of staff. The unrivalled star of the place, she sees hundreds of visitors file past her cage each day.

And, of course, each one of them has comments to make…

2010 / 70 mins / 35 mm colour / 1,85 / DTS SR

Photography Katell Djian, Nicolas Philibert • Sound Jean Umansky, Laurent Gabiot • Editing Nicolas Philibert, with the assistance of Léa Masson • Mix Julien Cloquet • Colour grading Eric Salleron • Production manager Katya Laraison • Post-production co-ordinator Sophie Vermersch • Original score Philippe Hersant, performed on the basson by Pascal Gallois • The traditional song “Dobri dien romale” is performed by Eric Slabiak and Franck Anastasio • The extract from Buffon’s “Natural History” is read by Valéry Gaillard • Co-produced by Les Films d’Ici/Serge Lalou, with the assistance of Laura Briand – Forum des images/Alain Esmery, with the assistance of Corinne Beal • With the participation of the menagerie of the Jardin des Plantes/Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle and CinéCinéma, Long Ride Inc., Centre National de la Cinématographie • Colour grading Forum des images / Avidia • Mix Archipel Productions • Optical transfer Ciné Stéréo • Subtitling CMC Paris • Laboratoires Eclair • French distribution & world sales Les Films du Losange • Release certificate n° 124 741 • © Les Films d’Ici, Forum des images, 2010.

With the voices of Abel and Lucie Morin, Agnès Laurent, Georges Peltier, Gaya Jiji, Eric Slabiak, Muriel Combeau, Diego Feduzi, Ludovico Lanni, Christelle Hano, Charlotte Uzu, Agathe Berman, Judit Kele, Zhang Xuequin, Linda De Zitter, Maria Charlès, Marianne and Mikhael Lalou, Marie-Claude Bomsel, Jean-François Sonnet, Gérard Dousseau, Catherine Hébert, Pierre Meunier, and of numerous anonymous visitors.

Official selection Berlinale 2010 (Forum) Berlinale 2010 • Best Director, documentary section, RiverRun International Film Festival (USA) 2011 • Grand Prize « Cinéma Vérité » Iran International Documentary Film Festival, Téhéran 2011.

French theatrical release : March 31, 2010

Distribution & world sales : Les Films du Losange

www.filmsdulosange.fr

This project came about at the end of 2008. One day, I went to visit the menagerie at the Jardin des Plantes. I hadn’t set foot there for years. On entering the “ape house”, I stopped dead in front of the orang-utans’ cage. A few visitors, laughing, were commenting on their every act and gesture. On her ledge, Nénette seemed to be miles away but, on taking a closer look at her, I realized that in fact she wasn’t missing one bit of the show that we were unwittingly providing… The idea for the film came to me at that point. In my mind, it would be a short film running fifteen or twenty minutes at the most but, as soon as I started shooting, I could tell that the face-to-face set-up was going to allow me to go beyond the initially planned running time. This was confirmed during editing. From that moment on, the film followed its own development without me needing to force things.

I wanted to film Nénette face-on, through the glass of her cage, the way visitors see her. Seize those troubling moments that seem suspended in time when she looks back at us. Of course, I also filmed the other three, Tübo, Théodora and Tamü: they share the same cage but, in the film, I haven’t given them the same place. The priority goes to Nénette. And yet, at first sight, she is the most discreet, the one you notice the least. She is often in the background, half-buried under the straw of her nest where she takes very long naps. She is probably saving her strength… given her age! She is also the only one not born in captivity but in her natural environment, in Borneo. I don’t know if that is what makes her more distant but she rarely approaches, unlike the other three who do not hesitate to come and press against the glass. Perhaps that’s what I liked. This distant presence, tinged with indifference, that gives her a sort of aura, a sort of sovereignty! A way of charming without trying to charm; of looking at the visitor without ever asking for anything in return and of flinging his so-called superiority and voyeurism back in his face.

600,000 people file past her cage each year, take her photo, film her, comment on the sight. They laugh, exclaim, sympathize, pity, admire her skill, her agility, the sheen of her fur; they philosophize, compare themselves to her, explain to their children; by reading the signs, they discover the extent of the threat facing the species, the massive deforestation, poaching… There are visitors who come every week, as if coming to see an old cousin; those who are there for the first time and who remain rooted to the spot; those who jeer, grunt, gesticulate, imitate her, ape her or pose endless questions about the pouch that orang-utans have under their chin. Seven days a week, winter and summer. For 37 years.

The film is based on the divergence between image and sound, meaning that we see the animals without ever hearing them and hear the humans without ever seeing them. There is no reverse angle. No cutaway shot. The soundtrack blends several kinds of words: the spontaneous comments of the visitors – families, couples, foreign tourists, a gang of adolescents, single visitors, students from an art school and their teacher, etc… But I have also recorded the keepers, especially the older ones: they saw Nénette grow and know her story. Finally, I asked a few friends from different backgrounds to come along and I recorded their reactions. Among them, Erik Slabiac and Franck Anastasio from the group Les Yeux noirs came to sing a gypsy tune. Valéry Gaillard, who was my assistant for some years before making his own films, came to read some pages by Buffon. Linda De Zitter, a psychoanalyst, chose Flemish, her mother tongue, to make a few remarks; and the comedian, Pierre Meunier came up with the long, totally improvised monologue at the end of the film…

Behind the glass, Nénette is a mirror. A screen for our projections. We attribute all kinds of feelings, intentions and even thoughts to her. In talking about her, we talk about ourselves. In looking at her, we include ourselves in the picture. Just as Flaubert declared, “I am Madame Bovary!”, so I could say, “I am Nénette.” She is you. She is us. And yet we shall never know what she thinks, or even if she thinks. The mystery remains. Deep down, Nénette is the perfect confidante: she keeps all secrets.

This is a film on the gaze, on representation. A metaphor for the cinema, in particular for the documentary, as capturing and as capture; after all, filming others is always a way of imprisoning them, of enclosing them in a frame, of freezing them in space and time.

Nicolas Philibert

The Independent - April 3rd, 2010

The director of Etre et Avoir has chosen the oldest inhabitant of the oldest zoo in the world as the star of his new film.

France’s newest female movie star is having a bad hair day. She is lying on her back, quite naked, playing with her toes. Her long red hair is covered with scraps of straw. She stares primly at her visitors and then, with a morose, bored expression – worthy of a Hollywood celeb – looks away.

Meet Nénette, 40, the oldest inhabitant of the oldest zoo in the world. The female orang-utan, long a favourite of generations of Parisian schoolchildren, plays the undisputed leading role in a new film by France’s most successful documentary-maker, Nicolas Philibert.

In 2002, Mr Philibert charmed audiences all over the world with Etre et Avoir, a laconic, lyrical movie about a single-class primary school in a mountain village in the Auvergne. His latest film, Nénette, follows, for almost all of its 70 minutes, the facial expressions, and slothful movements, of an ageing orang-utan in her glass-fronted cage at the menagerie in the Jardin des Plantes in the centre of Paris. There are continuous takes of the animal’s face which last for five minutes or more.

Nénette’s human visitors, and minders, are seen only as vague reflections in the glass of her cage. Her amusingly and disturbingly human expressions – boredom, curiosity, puzzlement, but mostly boredom – are accompanied by the dotty or admiring comments of the humans. “She is the same age as daddy”. “She doesn’t have much space but rents are expensive in Paris.” “She looks sad,” says an elderly female voice. “Maybe she has also lost her husband.”

By the end of the movie, the glass-front of the cage has become both a barrier and a mirror. Is Nénette really one of us? Or are we – the zoo visitors and the movie audience – projecting ourselves on to the unfathomable ape?

Mr Philibert, who has won critical acclaim and prizes all over the world for previous movies, is almost as inscrutable as Nénette. Unlike some documentary-makers, his style is not to bully the audience with tendentious editing. He leaves all options open. “I don’t like to tell the audience what to think,” he said. “I like just to discover what is before me.”

The idea for the movie came when he visited the Jardin des Plantes, and its celebrated – and controversial – 200-year-old menagerie in 2008. He set out to make a 15-minute short film and became more and more engrossed with Nénette.

“The film is as much about ourselves as it is about orang-utans,” he said. “Nénette is a mystery. We don’t know what she thinks or if she thinks at all … She is a receptacle for our fantasies. She is a projection screen … The monkey house where she lives is almost like a confessional. When they talk about Nénette, people talk about themselves…”

During a brief visit by The Independent yesterday, Nénette, the unknowing film star, was in typical form. She spent most of her time slumped on a broad shelf, occasionally playing with her toes or her fur. Whether awake or apparently asleep, she always kept one hand on a thick rope, as if preparing for a rapid getaway.

Nénette was born in the jungles of Borneo in 1969 but has lived in the menagerie of the Jardin des Plantes, on the left bank of the Seine, not far from Notre Dame Cathedral, since 1972. Of the four orang-utans in the menagerie, including her son, Tubo, she is the only one to have been born in the wild. Since the death last year of the menagerie’s celebrated, sex-mad 146-year-old giant turtle, Kiki, Nénette is the zoo’s oldest inmate.

Kiki was popular with visitors because of his constant amorous and noisy assaults on the other turtles, despite his great age. Nénette is popular, despite doing not very much at all. She has a reputation for being cantankerous and – unlike the other orang-utans – takes little interest in the clothed apes on the other side of the plate glass.

The menagerie at the Jardin des Plantes (Botanical Gardens) is the oldest, largely unreconstructed zoo in the world. It was created in 1793, in the midst of the French Revolution, to receive the royal collection of animals from Versailles. In 1871, when the Prussian army besieged the French capital, the zoo animals were butchered for their meat.

Up to a few years ago, the menagerie was, frankly, a disgrace. Until 2004, generations of bears had lived for almost two centuries in two narrow, stone-lined holes, equipped with a dank pool, a dark den and a log. Big cats, including lions and a Siberian tiger, lived in old-fashioned, cramped, black wrought-iron cages, built in the mid-19th century.

After years of complaints from the French league of animal rights, the larger animals have now been moved to more spacious quarters in the French countryside. The small zoo – still the target of complaints by French animals’ rights groups – says that it has “reorientated” its activities from entertainment to the “preservation of endangered species”. The cages for Nénette and the other orang-utans are relatively spacious. There is also an outdoor area which they can reach when the weather is warm enough.

Mr Philibert’s film does not ignore the moral issues involved in keeping wild animals in captivity. A poetic, concluding voice-over by a French actor, Pierre Meunier, draws attention to the deep scratches torn in the cage walls by the orang-utans, “apparently in frustration at their captivity”. Is Nénette’s moroseness and boredom, Mr Meunier asks, natural to orang-utans or the product of her unnatural surroundings?

The film-maker Mr Philibert, while shunning simple conclusions as usual, says that he was surprised to find that even Nénette’s keepers were critical of zoos. “Her principal carer told me that there was no more anti-zoo person in the world than himself … It is a complicated issue but people like him have helped to push zoos from being mere collections of captive animals to helping to preserve threatened species,” he said.

Orang-utans are a very threatened species. They are the only type of ape which is found exclusively in Asia. Their remaining habitat, constantly reduced by logging, is in the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra. “We are exterminating them by cutting the forests to make room for intensive agriculture, especially to produce palm oil for creams, beauty products and food,” said Mr Philibert. “Every time you buy a bar of chocolate from Nestlé you are contributing to the demise of the orang-utan.”

So are we destroying our relatives? The film-maker does come close to taking sides in the human/ not-so-human debate in the last seconds of his film. We are abruptly shown an unusually animated Nénette at feeding time. She is handed a yoghurt in a small plastic carton which she eats sitting up using a white plastic spoon. Nénette is also given several closed bottles of tea. She unscrews them between finger and thumb with a delicacy which escapes some humans when opening bottles of beer.

Mr Philibert will be grateful that the human traits of the orang-utan do not extend to extreme litigiousness. After the worldwide success of his school documentary, Etre et Avoir, in 2002, the “star” of the movie, an apparently mild-mannered teacher, sued him – unsuccessfully – for a share of the profits. So did the parents of some of the children. Nénette, one presumes, is unlikely to do the same.

Under threat: ‘Man of the Forest’ by Michael McCarthy, Environment Editor

The name orang-utan means “man of the forest” in Malay. The animals’ “human” characteristics include an ability to use tools, mostly to open fruit. Their hands are similar to humans’, with four long fingers and an opposable thumb (they also have four long toes and an opposable big toe, meaning they can grasp things with both their hands and their feet). Orang-utans can grow to 5ft high.

Like all the great apes, the orang-utan is now threatened with extinction in the wild, but although it is not the rarest – that distinction belongs to the mountain gorillas of Central Africa, which number only about 700 – it may be the most threatened of all.

The threat comes from destruction of their forest habitat on the two big Asian islands where they now survive, Sumatra (part of Indonesia) and Borneo (which contains part of Indonesia, and also Sarawak and Sabah). The forest is disappearing on a vast scale because of logging, burning, wholesale conversion of forest to agricultural land and oil palm plantations, and fragmentation by roads.

The orang-utans of each island, formerly considered sub-species, are now regarded as species in their own right. The Sumatran orang-utan (Pongo abelii) is the worst hit and considered as Critically Endangered in the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of nature; the most recent estimate suggests that only about 7,300 animals are left, in the northern part of the island.

The Bornean orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeu) is currently assessed as Endangered; the last population estimate, from 2003, was between 45,000 and 69,000 animals remaining, but since recent trends are steeply down in most places, it is thought that the current numbers are now below these figures.

Slant Magazine - December 19, 2010

Even before my conversion to veganism, zoos depressed the hell out of me. It’s still not exactly the sad, captive eyes or conduciveness to sadism that haunt me quite so much as the cautionary metaphor to be found in listless creatures occupying artificial habitats; like a grotesquely futurist Tati satire with sprinkles of Sartre, the zoo is a utopia brimming with beings that want for nothing aside from the viciousness of natural order. If harmless voyeurism is, to be diplomatic, the essential motive behind the zoo, then its unexpected lesson might be that we are vitally defined by our private battles for survival—and that we are, ultimately, conditioned to thrive most contently in environments that deprive us of desires. Simply granting us our basic needs and individual whims might be the most pernicious kind of existential cruelty.

The friction between this truth and our curiosity in caged animals is part of what powered Nick Park’s Oscar-winning animated short « Creature Comforts »; the grievances of real British tenement dwellers were wittily rendered as those of anthropomorphized turtles, hares, and (most memorably) cougars, all of whom appeared to bemoan the walls that immediately surrounded them. Where that film, however, was an ironist’s diatribe, the success of Nicolas Philibert’s similarly themed documentary « Nénette » is ponderously literal. For a little over an hour we watch the title character, a 40-year-old orangutan who for decades was the main attraction at Paris’s Jardin des Plantes, languidly sprawling about the branches in her exhibit, gnawing and pawing at packages of yogurt and tufts of straw, and (seemingly) accepting the fascination of off-screen visitors with tired contempt. Philibert furthermore widens the gap that Park cultivated between his audio testimony and his illustrations, using the wide-eyed and contemplative testimony of human onlookers and orangutan experts (along with a few distracting flourishes of non-diegetic music) as a soundtrack to Nénette’s sleepy exploits. And the documentary becomes, eventually, less a study of a great ape than a quiet reminder of how zoos act as a reflective prism for our livelihood-oriented anxieties.

The film’s narrative elliptically presents a series of contexts through which we glean Nénette’s rather epic story. Her handlers nostalgically recount her birth in captivity, the difficulties of her feisty adolescence (she couldn’t even be touched without sedation until later in life), her inevitable encounters with an adoring global media, and the medical events that catalyzed her decline into docility. Each of these biographical anecdotes is paired with a bystander’s monologue that free-associates with her current state: one zoo-goer is reminded that “in [ancient] Egypt, they killed redheads after birth…because of the devil”; another becomes obsessed with Nénette’s lack of a mate (“You need someone, even at her age,” she whispers). The orangutan’s exaggerated humanoid behavior provokes fancy, philosophy, alarm. She becomes a noble mascot of endangerment, an impetus for an argument about gender politics, a slightly shaggy iteration of Shakespeare’s paragon of animals, and even, when younger orangutans threaten her Parisian spotlight, an icy if impotent Margo Channing.

Throughout, Philibert breaks from his verité credentials to photograph Nénette and her alpha son, Tübo, in a painstakingly varied assortment of camera angles; we see her bulbous lips flapping in close-up, her muscular limbs extending to unknowingly thumb the tip of the frame, and her pendulous breasts pressing into glass partitions just above us. (The film almost joking inverts the typical talking head concept into footage that is “all action, no content.”) But aside from occasional reflections of gawking school children or nearby ape habitats, we don’t get a clear sense of the borders of her world or what lies beyond. This visual isolation ensures our intimacy with Nénette and underscores the documentary’s most lucid and disconcerting argument—that mankind is the orangutan’s border. Our relentless gaze is the entirety of Nénette’s contact with the outside world, and our frontal lobe-sporting species is the apogee of the primate order. And yet this realization isn’t accompanied by a sensation of responsibility ruefully shirked; we feel instead exposed and vulnerable, stationed at the defiant outskirts of an organic community, waiting to see where nature will take us next.

« Nénette » thankfully doesn’t dote on its subject’s obvious sadness, though it occasionally yields to an undercurrent of heavy-handed sympathy; in one scene, the orangutan absent-mindedly licks the edge of her cubicle while plaintive mariachi music plays and metal doors in the distance clang with prison-like authority. Elsewhere, however, Philibert uses his pity to fuel a more eloquent if passing observation of the way we minoritize our own. “There’s a legend in Borneo,” one interviewee claims, “that Orangutans can speak, but remain silent so they won’t have to work.” The connection, however soft, to the xenophobic stereotyping of any subculture is startlingly undeniable; when another patron rhetorically asks later, “Is it really enviable—having nothing to do?,” we can’t help but read it as a defensive murmur from a member of the disillusioned, downward looking elite.

« Nénette » isn’t quite Malthusian in its outlook, but it clarifies just how grim the view is from the claustrophobic “comfort zone” of the food chain’s top—ethnically, economically, environmentally. We might be responsible for our own four walls, but that doesn’t mean they don’t distribute the same superficial sustenance that Nénette receives. As Captain Beefheart passive-aggressively intoned in his kindred spirit of an apostrophe to a zoo creature named Apes-Ma, “Your cage isn’t getting any bigger.”

The New York Times - Décember 21, 2010

A child’s voice whispers “ Nénette! ” and immediately we are in the patient and curious world of the French filmmaker Nicolas Philibert. Best known in the United States for To Be and to Have – his captivating 2002 portrait of a rural schoolteacher – Mr. Philibert has switched his gaze to a primate with rather less agency: a 40-year-old female orangutan in the zoo at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris.

That gaze never wavers. « Nénette » is a film devoid of human faces, the camera merging with the more than half-million visitors who traipse past the orangutan’s cage every year. We hear their voices, these mothers and children and couples, their words revealing the complexity of our relationship to caged wildlife. Is Nénette depressed, they wonder, or just lonely?

Quiet and watchful, the object of their fascination leans on her gnarled knuckles, straw clinging to her mat of ginger hair. She arrived from Borneo in 1972, has survived three mates and produced four offspring. Once she was lively (“The bane of the place,” says an older zookeeper); now she looks passive and glum, quieted by age and arthritis. Or something else.

Beautiful in its minimalism, « Nénette » is no antizoo rant but a melancholy meditation on captivity. Nénette may be better off than her endangered kin, but as we watch her delicately pour tea into the yogurt container that holds her contraceptive pill (she lives with her son, and the zoo is keen to avoid procreative embarrassment), that knowledge gives us small comfort.

Yet Nénette is loved, with some people stopping by every day. A keeper likens them to those visiting a relative in prison — which, when you come to think of it, is exactly what they are doing.

« Nénette » will screen with Creature Comforts, Nick Park’s delightful animated short film from 1989.

Art Forum - December 21, 2010

A JOLIE LAIDE red-haired Parisian of a certain age with four offspring by various mates, Nénette lives with Tubo, her youngest. Her address: Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, 5ème. Nénette is a forty-year-old orangutan, probably the oldest of her species in captivity or in the wild. With her fertility status unknown, her caretakers have put her on the Pill as a precaution. They do not know whether orangutans observe the incest taboo, and if Nénette should become pregnant again, her health might be endangered. Not to mention that it would look bad for the zoo’s breeding program, the rationale for any zoo’s existence. With their natural habitats severely diminished, orangutans are an endangered species.

« Nénette » is the titular subject of an oddball documentary by Nicolas Philibert, who is best known for To Be and to Have (2002), a captivating study of a French village grade school and its only teacher.To Be and to Have was an unexpected critical and popular success, in part because its empathetic teacher and his energetic young pupils felt like a beacon of hope in troubled times. Sadly, a shadow was cast over the movie when the teacher and some of the students’ parents sued Philibert for a piece of the profits, claiming that they had been led to believe that they were participating in an educational film with no commercial value. They lost the suit, the filmmaker’s lawyers countering that if their demand was upheld, it would have a chilling effect on documentary moviemaking in general.

It goes without saying that Nénette is in no position to drag Philibert back to court, and since she has spent her entire life as an object of the gaze, one camera more probably doesn’t matter to her. Still, Nénette ’s subtext of subject-object relations and its setting – an institution where power and freedom are absolutely entwined – account for the unease it generates along with delight. The issue of zoos is little discussed, although some of Nénette’s keepers express grave reservations about keeping wild animals in captivity. The zoo in the Jardin des Plantes was renovated about five years ago, and the indoor cage and slightly more spacious outdoor enclosure that Nénette and Tubo share with two other orangutans are palatial compared with the “Ape House” in which Nénette lived for thirty years after she was brought from Borneo.

Hardly a candidate for a slot on Animal Planet, T« Nénette » is structured by a complete separation of image and sound. A star attraction at the zoo, Nénette is the focus of almost every shot in the movie, some of them sustained for five or more minutes. There are a few cutaways to the three other orangutans, but there are no reverse angles—the only glimpses we have of Nénette’s human visitors and caretakers are as occasional indistinct reflections on the glass of her enclosure. On the sound track, however, we hear nothing except human voices—a collective stream of consciousness that mixes casual spectators, Nénette devotees, various zookeepers, and one or two scientists and philosophers. “They used to kill redheads at birth in Egypt,” says one woman. “She’s going through the stages of her life [in her mind],” opines another, of the diffident Nénette, who seldom interacts with her visitors and spends long periods of time doing nothing or performing household chores—arranging the straw of her mattress, wrapping herself in the bedclothes and then tossing them aside.

Like all great stars, Nénette is an enigma, She is more withdrawn than the other orangutans, perhaps because of her age, as one keeper speculates, or perhaps because she was born free. In the wild, orangutans spend much of their time high in the trees, simply observing the world around them. Nénette replicates this behavior in captivity, watching the people who watch her but without interacting. In this she is the alter ego of Philibert, a maker of observational documentaries. Indeed, the first shot of « Nénette » is an extreme close-up of the star’s rheumy, deep-set eyes; the unseen camera’s electronic eye stares into the animal’s eyes, revealing nothing about Nénette but worlds about our desire to transform perception into knowledge and power.

Late in the movie, we hear a man who seems to be an actor (he is the comedian Pierre Meunier) try to account for our fascination with Nénette. “The quality of her idleness,” he says, “makes me think of an acting exercise: ‘Ladies and gentleman, the space is yours to do whatever you want.’ A difficult exercise,” he continues, “when watched by others.” In the late afternoons, Nénette performs the routine that is most intriguing to her audience: She takes tea. First she unscrews the cover of a small plastic bottle, sips a bit of its contents, and carefully sets it down. Then she opens a container of yogurt, takes a spoonful or two, unscrews a second bottle, samples its contents, pours some of it into the yogurt container, and drinks the mixture. Does this daily ritual—an uncanny mimicry of human behavior—give her pleasure? We hope it does, but who is to know?

The Boston Globe - January 21, 2011

The star of Nicolas Philibert’s entrancing 67-minute documentary, Nénette, is a 40-year-old orangutan who lives in a deluxe tank at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. She is large, arthritic, and stupendously hairy — her fur appears tinged with copper — and, above all, sad-looking. Her days are spent shoving fistfuls of hay into her mouth, methodically removing bottle caps in order to sip an assortment of beverages, hiding under quilts, and staring glumly at her visitors. Nénette came to France from Borneo in the early 1970s; and the Jardin’s modest zoo, which is nestled amid the far larger and more famous botanical garden, is the only home she’s ever known.

Philibert’s film finds a rather contemplative creature. Her mood complements his. The camera sits at clever angles taking in her three housemates, one of whom is her son, Tubo. Outside the frame, visitors speculate, in various languages, about everything from Nénette and Tubo’s moral well-being and anatomy (how many breasts do they have?) to their gender (he’s commonly referred to as “she’’; and to be fair, his magenta bowl-cut resembles one that the esteemed French director Agnès Varda has been wearing for years). The head zookeepers discuss, with each other and once with a visitor, the habits, back story, psychology, and physical condition of the clan. Some of what they say is surprising. No one, for instance, seems to know whether Nénette is menopausal.

Philibert never matches the stream of voices with an actual mouth. People are reflections in glass, audio commentary without a physical corollary. This is as it should be since whom they’ve come to watch or are paid to look after are far more interesting. The placement of the camera also proves as bright an egalitarian choice as, say, holing up for a year at a country schoolhouse, as Philibert did in 2002’s To Be and to Have, one of France’s most popular documentaries.

Beyond receiving permission to film at the Jardin, Philibert doesn’t appear to have any glorified access. The camera remains on the spectator’s side of the glass. Often it gets close enough to sustain the illusion of an evaporated partition. The zoo — at Nénette’s corner in particular — seems very much as it would on most other days. Both the steamed glass of some parts of the tank and the requirement to stare up from low angles are normal. Philibert is clever enough to glean, in the angles and foggy glass, the potential for art. The many long glances up at Nénette and company contribute a dimension of wonder and admiration. But the mix of long takes and brisk, playfully assembled sequences imparts an air of caprice. Who said observation couldn’t include visual rhythm or montage?

The mutual watchfulness — the orangutan’s and the director’s — makes them kindred spirits. More often than her son or the tank’s two younger, more crowd-pleasing residents, it’s Nénette who’s shown looking out at the strangers staring in at her, doing so with the sort of blank naturalism that’s made Isabelle Huppert an international treasure.

The Guardian - January 28, 2011

An elderly orangutan is the star of Etre et avoir director Nicolas Philibert’s new documentary. But the real action is going on outside the cage, he tells Catherine Shoard

The star of Nicolas Philibert’s new film picks sceptically at her lettuce. From behind lavish lashes, she regards the crowd below, auburn hair flaming in the sunlight. Her director waves and smiles. After a pause, she advances, and, with a poise that bespeaks 38 years in the public eye, slowly runs her tongue, big as bacon, over the glass. Politesse dispensed, it’s back to her tyre for a scratch.

We’re in Paris’s Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, beside the Seine, off the Boulevard St Germain, on a perishing morning. Outside, in pens whose size testifies to the place’s age (built in 1794), an ostrich hammers at the frost. A yak snorts. Doleful? Or just cold?

Philibert, 60, smiles and shrugs and hops gently from foot to foot, trying to keep warm, and to coax his star from her shell. The zoo’s ape house, unlike the rest of the premises, is built like a ballroom. But while visitors have ample space to run riot, the primates crouch in cages fringing the perimeter.

He suspects the depression we detect from Nénette, the 41-year-old orangutan centre-screen for all 70 minutes of his latest documentary – which shares her name – is a projection of our own emotions. “People think that they’ll see monkeys and have fun,” he says. “They associate them with acrobats and mischief. But after half a minute here, they stop looking. Because they are struck by something more tragic. They start thinking about the situation of these animals in the wild and about what we are doing with our planet.”

The film (low on the eco moralising, by the way) shows us long, semi-hypnotic shots of Nénette, swaddled in a blanket or sucking apples or grooming her son, Tubo. Over these, we hear – but never see, unless in watery reflection – visitors, clamouring behind the glass: excited, indifferent, rude, moved.

A child exclaims at Nénette’s advanced age. A woman wonders whether Tubo has a mate (Nénette, incidentally, having outlived four husbands, is now on the pill, lest she and Tubo become too close). A man says she must be homesick. A keeper explains how Nénette, once a great star, was upstaged by younger models, including, crucially, one who could tie knots. Another reports that she found holding Nénette more rewarding than cuddling her own children – the ape gripped tighter.

“I wanted to focus on the opposition between Nénette’s inability to talk,” says Philibert, in good-humoured, halting English, “and humans talking in a babble – in different languages, with different sort of levels of interventions, both serious and humorous.”

Much of Philibert’s previous work has also focused on those who have trouble expressing themselves. In the Land of the Deaf (1994) shows us a school for the hard of hearing; Every Little Thing (1997) chronicles the staging of a play in a mental institution. His best-known movie, 2002’s Etre et Avoir, which won an Oscar nomination and distribution across 40 countries, comprises scenes from a village school in the Auvergne, the magnificently calm teacher wrangling a dozen children between four and 11.

For Nénette, he’s upped the stakes: his subject is a mute ape. Or is it? The longer one looks at the film, the less it seems to reveal; the more Nénette appears to be just a great, hairy MacGuffin. The real subject – as evidenced by Philibert’s editing priorities (human audio first, monkey images to follow) – is us.

So what makes Nénette such a revealing mirror? Philibert grins again and gives one of what turns out to be his signature laughs, heavy on the humming, big on twinkles. “It wouldn’t be the same if I had filmed a cow. We do not identify with a cow or with a spider. But Nénette is at the same time both close and mysterious.

“This mystery I wanted. That’s why I didn’t interview scientists. A film is not a scientific book. For me, cinema is about strangeness. I do not make films from knowledge but from my own ignorance. The less I know, the better I feel. Nénette is like the Mona Lisa. You can’t help asking many questions. They do not have answers.”

And, like that painting, Nénette is a destination for repeat visits, a fixed point for people while their life outside mutates. “I saw an old lady come into the ape house and bow in front of Nénette as if she was the Queen. It was amazing.”

Did he tape her? Philibert looks surprised. His shock of hair seems to rise yet higher. “No, I didn’t want to disturb her. She was in a bubble.”

What distinguishes Philibert’s work – more than its unobtrusive intellect, or its measured aesthetic – is its compassion. Small wonder that in the flesh he’s a man with a rare ability to put you at your ease, to be patient and observant. No, he says, he would not dream of troubling others in pursuit of a quote, would never shoot someone unhappy to be on film.

The story, for him, is not worth the upset – indeed it’s not really about the story at all. His films are as open-minded as you can imagine. Although Nénette can be viewed as an oblique essay on cinema itself, a mediation of voyeurism, Philibert doesn’t aspire to journalism in his film-making, nor to the condition of fiction. “Documentary is the recreation of an event that you create through the choices you make when filming and editing. Each time I finish a film, I invite friends and family, and one of my uncles says: ‘It’s very nice but when will you make a real film?'”

Born in Nancy in 1951, Philibert studied philosophy, then, while teaching film theory in Paris, made a series of quiet documentaries that won him acclaim in his homeland. Wider fame didn’t really come until Etre et Avoir, and was then complicated by an unsuccessful lawsuit launched by the teacher and some of the parents of the children, keen for a larger cut of the profits.

Such a souring action may, it’s tempting to think, have hit him hard. It was five years before he made another film, Return to Normandy, in which he revisited the location for a shoot on which he was assistant director in 1976. It was atypically personal: he provided a voiceover, and revealed that part of the reason for the project was to try to unearth lost footage of his late father.

Nénette, too, is more of a departure than it might initially appear. Philibert’s commitment to making cinema in collaboration with his subjects had to be discarded. “I don’t feel guilty not having asked her if I could film. Maybe I would have stopped if she had reacted badly or been frightened, but hundreds of people film her every day, take pictures.”

Likewise, the movie unfolds outside a community – in contrast to the hopeful utopia shown in, say, Every Little Thing or In the Land of the Deaf. “It is encouraging to be with such people. They are fighting and struggling for better lives. We all try to live together and build something together, to share something.”

Nénette, by contrast, offers a much more negative reflection of humanity – one whose pessimism Philibert appears to share. “Human beings,” he says, “are archaic and savage.” He looks downcast rather than wry, moustache suddenly droopy. “They are able to act much worse, and more wildly, than animals.”

It’s a strange mix: this sadness, and such a persistent interest in everyday life that one collaborator likened him to a curious child. “I really think that the quality of a film is not linked to the dimension or the exoticism of the subject,” he says. “We can be surprised when rewatching our everyday gestures. You can make a film at the next corner. You have stories, futures, present, past, women, men, children, people in love, people suffering, people working hard.”

Whether Nénette is about the ape behind the glass or the man behind the camera matters, finally, less than the making of it. “To continue to live,” says Philibert at one point, “I need to film.” For us, too, it’s consolation.

Little White Lies - February 3, 2011

Nicolas Philibert’s film is at once a humbling, enlightening experience.

For the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes in Paris, monkey business is big business. Every day scores of tourists cross the Seine and flock to the world’s oldest zoo to catch a glimpse of its star attraction – a 41-year-old female orangutan named Nénette.

Snatched from her Bornean canopy when she was still a tree-swinging monklet, Nénette has spent the last 38 years in captivity, confined to an interior space that puts most Paris apartments to shame but is a far cry from her former tropical digs.

Separated by a large perspex frame, the zoo’s patrons watch Nénette eagerly, hoping to catch glimpses of the mischievous arboreal antics associated with these loveable copper-haired simians. It’s an artificial communion, of course, one that Nénette is long accustomed to and largely nonplussed by. While children smile and cameras flash incessantly, Nénette idly passes the hours, exerting as little energy as possible while leaving the circus act to her son Tübo and other, more exuberant bedfellows.

She cuts a forlorn figure, for sure, but is she ‘depressed’, or are concerns for her emotional wellbeing merely a projection of human compassion for our fluffy cousins? Shrewdly, documentarian Nicolas Philibert doesn’t openly form an opinion either way, instead allowing visitors’ conversations – by turns painting Nénette as a tragically repressed soul and a mangey ape – to play out over static close-ups of our star subject.

The reality is that Nénette is just old. In her rich life she has succeeded three mates and mothered four children, surviving as the zoo’s longest-serving resident, and now seems perfectly content lounging around drinking tea and lackadaisically munching her greens – caged but safe from nature’s perils and the ever-destructive hand of man.

Captivity today is more of a social conundrum than a barometer of human supremacy on this Earth, but « Nénette » shows that we as a species are unable to disassociate our behavioural characteristics with those of other primates. Those deep, dark eyes are so expressive, so familiar, if only she could part those wide rubbery lips and speak!

Herein lies the film’s unspoken truth. As Nénette sits slumped in silence, sucking fruit and scratching her nether regions, it is left to those strange creatures on the other side of the glass to assess her mental state and tell her story.

Little White Lies - February 3, 2011

In his 30 plus year career, French documentarian Nicolas Philibert has filmed everything from the hidden treasures of the Louvre; to the disquieting tranquility of the La Borde psychiatric clinic; to an isolated schoolhouse in Auvergne, rural France, in the BAFTA nominated To Be and to Have. His latest subject is one of France’s most cherished celebrities, an unlikely star who resides in Paris’ famous Jardin des Plantes. LWLies caught up with Philibert recently to discuss the making of « Nénette » and the delicate balance between man and nature.

LWLies: « Nénette » is something of a departure from your previous work, how did the film come about?

Philibert : The idea came very spontaneously when visiting the menagerie. Often a film project needs to grow slowly out of something in your mind, but this one came very quickly to me. The idea of separating the images and sounds came on the very first day.

Was that an important decision to make so early on?

Yes because the film is a face-to-face, it’s a mirror and because of that we don’t need to see any humans. In my opinion the message is much stronger if we don’t see people, only Nénette and the others here and there. It’s a film about the projection itself, because when we see these animals we can’t help projecting our own feelings and thoughts. What is looking? What is voyeurism? We pay to watch animals behind glass in their cages, like when we go to a peep show. It’s an interesting facet of human nature to explore.

What drew you to Nénette specifically?

I think I identified strongly with her because she is so famous – a celebrity in France – and there is something about orangutans that is so remarkable. They are very human. We don’t associate ourselves with chickens or rabbits or spiders but orangutans are very close to us, they are our cousins, we share 97 per cent of our DNA with them. They seem to imitate us a lot, especially in captivity where they see humans from 9am to 6pm everyday for years on end.

How did you shoot the film?

It was 10 days, one hour a day. Not that much, really. We had about 10 hours of images and more sound recordings at the end of the shoot. I didn’t shoot scenes or set up shots, I just left the camera rolling. And there’s very little synchronisation between the images and sound, apart from a few of the interviews with the keepers. Otherwise I just left a small recorder next to the glass and captured people’s conversations and comments. To be honest, when editing I started from sounds and built up the images on top, it was very important to get the sound sequenced first, to build up a narrative.

What do you make of the relationship between Nénette and her keepers?

It’s funny because they know her habits so well and they are all very fond of her, but maybe they see her as more than an animal. I don’t know. It’s easy to fall in love with her.

How much do you feel you bonded with Nénette while you were filming?

She’s a star, you know, she’s been filmed for years and there’s always people taking photos of her everyday on phones and cameras. But as I came back after each day I noticed that she could recognise me. After three days she knew who I was. I learned a lot of things about her; after just a few hours I could distinguish between Nénette and the other three orangutans by her movements and subtle characteristics.

What works so well about the film is that fact that you keep your own thoughts private, but what do you think about captivity and what it means today?

Well the film says enough without me having to share my thoughts, but if you want to know… I think that when we are kids we love zoos and the magic of seeing exotic animals, but when we are adults we don’t like them because as we get older it becomes a synonym of jail and something very negative. But zoos are important now; they’ve changed what they stand for because in the wild these animals are not safe. We are quickly achieving to exterminate these animals in the wild, and the irony is, of course, that they are now in less danger behind glass. It is said that within 15-20 years there won’t be any more orangutans in Borneo and Sumatra. We are destroying the forest and there’s no way for it to recover in time to save this species. That is so sad to me but it’s really too late to do anything now so most likely these animals will shortly only exist in captivity.

Time Out, London - February 9, 2011

French documentary-maker Nicolas Philibert’s latest is a compassionate, thoughtful portrait of Nénette, a jocular 40-year-old ape from Borneo who counts the zoo in Paris’s Jardin des Plantes as her home and its staff as her family. We observe Nénette through finger-pawed glass as she sulks in a corner, tumbles around with her son or sloshes down tea, yoghurt and medication. Nénette is a simpler, purer work than Back to Normandy (2007), an indulgent film which piled up questions about the consumption and creation of art, but delivered no real revelations. It’s more in the vein of beloved rural school doc Etre et Avoir (2002), as the director takes pains to hide his own presence and give centre-stage to his magnificent subject, although this is certainly more experimental and demanding on the viewer.

Small details are magnified by Philibert’s long, quiet takes, and Nénette’s mundane human characteristics make us consider our own lives and how we relate to the natural world. Are we wrong to apply human ideas to her? We’re told that, docile as she seems, Nénette’s upbringing was painful and until recently she met human contact with violent indifference. Of course, some may feel sad that we only see her in a sparse, sanitised environment, and Philibert earwigs on the reflections of those who pass by the zoo so we can develop our own ideas about whether casual voyeurism merits a lifetime in captivity. And if big questions aren’t for you, this is still just a wonderful film to gawp at.

Time Out,London - February 9, 2011

In Etre et Avoir he captivated us with the daily doings at a one-room school in deepest rural France. In Back to Normandy he made us care deeply about what happened to the cast and crew of a 1970s French film few had ever heard of. Ace documentarist Nicolas Philibert is obviously a man who likes a bit of a challenge, but – honestly – asking us to spend a full 70 minutes watching an elderly orang-utan in a Paris zoo? With Nénette, he’s having a laugh – surely?

‘I know, it’s absurd,’ admits the 60 year old from north-eastern France. ‘I won’t do it again. Promise.’ This he says with a cheery giggle. When we meet at last year’s Edinburgh Film Festival, it’s obvious that this rather jolly, unassuming man doesn’t take himself too seriously – but is, of course, deeply thoughtful about his craft and cinema in general. If that seems like a paradox, then Philibert is full of them. Try this one, for instance… ‘The beauty and importance of a film aren’t linked to the subject. You can make a bad film from a so-called “important” subject, but you can also make a great film from a theme that seems tiny or banal.’ Like an ape sitting in a cage, he means, though Nénette was a project which came together ‘petit à petit,’ he says.

After visiting the primate house in Paris’s Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, a venerable institution dating from 1794, he was struck by Nénette, a Rubenesque widow who’s been on display for 38 years. She’d outlived four husbands and, unlike three other orang-utans in the same pen, had grown up in the wild. Intrigued by her distant manner, Philibert came back a few days later with his video camera, shot for a few days more, then edited and filmed some more. What started out as an idea for a 15-minute short grew and grew, in part because Philibert built up the soundtrack first then added the visuals, thus playing the images of Nénette in her cage – lolling, peering directly at us, remote, and tragic – against the constant chatter of sundry unseen spectators, whose comments reveal their own neuroses, often to pointedly comedic effect.

‘As soon as I started I knew I was making a film about cinema,’ maintains Philibert, immediately dispelling any notions one might have that this is ‘just’ a portrait of a fascinating distant relative. ‘Behind the glass, Nénette is a surface on which we project. Behind the transparency, there is opacity, something as mysterious as the Mona Lisa. So she becomes the surface on which we see our own projections, our fantasies, our imagination. Nénette is “the other”, par excellence. Close to us, yet out of reach, and somehow frightening…’ Frightening and more, in fact. Although the prospect of spending 70 minutes in Nénette’s company is daunting at first, Philibert’s film works like he says it does. There’s something about the way she looks back at you which gets you thinking about your life in comparison. Are we all that isolated? Are we all that constricted by those who claim to have our best interests at heart? Is our species doomed too? What does it say about us that we put our closest relatives in the animal kingdom in cages? Or that we let them face extinction in the wild in the first place? What once seemed like a tiny theme balloons out in issues of morality, common humanity, self-knowledge… in essence, it’s whatever you make of it. ‘Of course, it’s a peep show, it’s about the nature of documentary, documentary as a kind of voyeurism,’ adds Philibert, gathering steam. ‘What it’s not is an “animal documentary”. I didn’t include comments from scientific experts on the apes or the environment, because I wanted Nénette to retain her mystery. If a film answers in advance all the questions an audience might have, then the viewers don’t have to participate. They’re just passive. I want to keep the questions open.’ But the structure, the material is shaped in a way that prompts our questions, it’s not just open plan, anything goes, right?

‘Of course, I have a point of view, obviously. But it’s not didactic. When you make a film, you pretend you’re in control of everything. Master of the world. But there’s so much you don’t know about what you’re doing. So much that’s invisible, and you have to admit that.’ So creative control is about surrendering control. Well, we did say he was Monsieur Paradoxe. ‘There’s nothing better, from my point of view,’ he sums it up, ‘than learning something new about the film you’ve made from the responses you get from viewers. It’s just lovely when they appropriate it for themselves.’