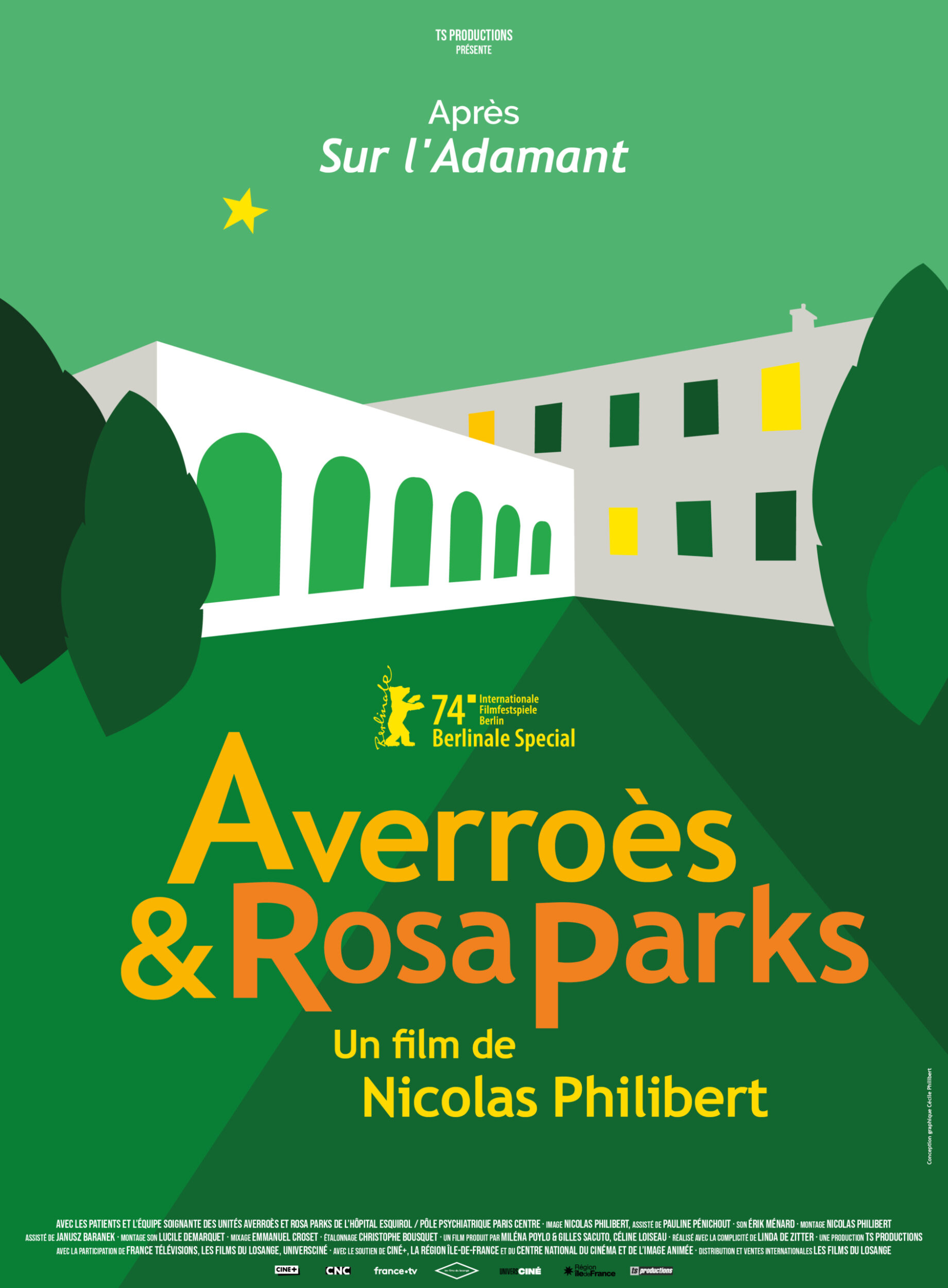

Averroes and Rosa Parks: two units of the Esquirol Hospital, which – like the Adamant – are part of the Paris Central Psychiatric Group.

From individual interviews to “carer-patient” meetings, the filmmaker focuses on showing a form of psychiatry that continually strives to make room for and rehabilitate the patients’ words. Little by little, each one eases open the door to their world.

Within an increasingly worn-out health system, how can the forsaken be given a place among others?

This film was made with the complicity of Linda de Zitter

Image Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Pauline Pénichout and occasionally by Katell Djian • Sound Erik Ménard • Drone shots Emmanuel Fraisse • Editing Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Janusz Baranek • Closing credits music Sarah Murcia and Magic Malik, based on The Ode to Joy (Ludwig Van Beethoven) • Sound editing Lucile Demarquet • Mix Emmanuel Croset • Colour grading Christophe Bousquet • Post-production supervisor Delphine Passant • Producers Miléna Poylo & Gilles Sacuto, Céline Loiseau, assisted by Clément Reffo, Coline Perraudin, Joseph Sacuto • Produced by TS Productions • With the participation of France Télévisions, Les Films du Losange, Universciné • With the support of la Région Île-de-France, in partnership with the CNC • With the support of Ciné+, Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée.

With the patients and carers of the Averroes and Rosa Parks intra-hospital units, Esquirol Hospital, Charenton-le-Pont.

French distribution & international sales : les Films du Losange

French release : March 20, 2024

Birth of a triptych, by Nicolas Philibert

Before I began shooting On the Adamant, I had told myself that this highly original day centre – built on water – was a sort of autonomous little island, not necessarily closed in on itself, but fairly self-sufficient, say. I of course knew that the Adamant was part of a greater whole, the Paris Central Group, that also includes two medical-psychological centres, a mobile team and two care units, aptly named Averroès and Rosa Parks, within the Esquirol Hospital – formerly known as “The Charenton Asylum” – but it was as if, afraid of spreading myself too thinly, I refused to see how complementary and interdependent these different structures were and how they formed, with the Adamant, a network within which patients and carers were continually urged to circulate, each one able to “build his or her own cartography between the different points of reference at their disposal”. Subconsciously perhaps, I had needed to detach the Adamant from its context as if to single it out more clearly.

Once there, I quickly realized that this off-screen world had to be given an existence, if only in an allusive manner, at the risk of falsifying reality. Images are always misleading, you may say, and relating what we see is only ever one reading among others, an interpretation, but, even so, completely masking this plural dimension would have been an aberration. While the Adamant attracted attention, the other structures, more classical, were no less essential. The two medical-psychological centres were snowed under with requests and it took months to obtain an appointment. At Esquirol, Averroès and Rosa Parks were continually jam-packed. Moreover, several “passengers” on the Adamant with whom I had good contacts were staying there. I am thinking notably of Olivier with whom I had shot a sequence at the drawing workshop that had overwhelmed me, or François, the man who would open the film – once edited – by singing La Bombe humaine. Tearing themselves away from the hospital required them to make a huge effort. Getting up, dressing, crossing the grounds and going as far as the metro were often insurmountable tasks.

One day, I decided to visit them there. The Averroès and Rosa Parks units share a single building around a tree-filled patio. Averroès is on the ground floor and Rosa Parks upstairs. Neon-lit corridors, doors fitted with portholes, small single or twin rooms, a TV room on each floor, a few rooms set aside for meetings, mismatched chairs, a self-service restaurant. On the diagonal of the patio, a welcoming greenhouse where the Tuesday “carer-patients” meetings, the Wednesday morning “bar” and the few remaining workshops are held. That day, Olivier was busy, but I spent two hours talking to François. The perceptiveness with which he related his experience of more than thirty years in psychiatric care made a strong impression on me.

I returned over the following weeks and met other patients. Some seemed to be on the edge of the abyss and avoided all contact. Others were happy to have someone to talk to. Romain, thirty or so, spent his days “watching the plants grow and doing magic tricks.” Great! He took a pack of cards out of his pocket and did several tricks for me that all failed miserably. He was a little put out but ended up laughing about it. Eva had been hospitalized “at the request of a third party”. This wasn’t the first time. “I become obsessed… When I grow fond of someone, I find it hard letting go, and it turns into harassment.” Myriam did not want the others to hear her story. We met in the TV room. As part of her therapy, she had just unlocked a traumatic experience repressed for forty years. Placed in the care of her uncle and aunt at birth, she was abused by her uncle until the age of five. If I came back with the camera, she would testify: “It will help me,” she said. But she would leave the hospital a few days later.

Each one of them seemed walled up in abyssal solitude. From one visit to the next, I noticed new faces. Absentees too. The rotation was unending. Some weeks, the shortage of beds was such that admitting a new patient meant that another had to leave. But which one? A headache. I met the nurses, the health auxiliaries, the psychiatrists, the psychologists, the social workers, the administrative staff. Many of the nurses and health auxiliaries were temporary hires. Everyone was under pressure. I cautiously expressed my wish to come and shoot “a few extra shots” that would help to create the link between the Adamant and the hospital. The idea was greeted warmly. Nearly everyone knew about the filming taking place at the day centre and they had clearly heard good things about it. I was invited to attend a meeting. Then the morning staff briefing. Then the Tuesday “carer-patient” meetings. Occasionally stormy, always colourful, it was not unusual to see a patient rebel, hurl abuse at the medical team, start railing against psychiatry, medication, living conditions in the hospital, the French Republic, the Vatican, the food, the coffee… Extra shots? Deep down, I felt I’d moved beyond that. The idea of a second film went through my mind. In it, I wished to focus on the consultations, those individual interviews between patients and carers. An approach that I had left to one side on the Adamant. It’s true that one-on-one interviews are less frequent there.

Yet, at the same time, a third film had already begun to take shape. A few days earlier, I had had the opportunity to accompany and film two eminent members of the Band at the home of Patrice after the latter’s typewriter had begun to play up. The Band is a small group of carers who are skilled with their hands and who, not content with restoring souls on the Adamant, occasionally go to patients’ homes to do odd jobs: fixing a bookshelf, unblocking a washbasin, mending a plug, assembling a piece of furniture, etc. Patrice is an emblematic figure at the day centre. Winter or summer, this seventy-year-old man arrives every morning as soon as the place opens, goes to sit at “his” table, drinks a coffee and, without any further ado, begins writing a poem in alexandrines. When he gets home, he settles down at his typewriter and transcribes the day’s poem. This highly regulated ritual seems to be what has kept him going for years. With his typewriter suddenly on the blink, he was in a terrible state. Walid and Goulven offered to stop by, without any guarantee of success. Both in their thirties, they had never seen a typewriter before… except in movies. They got to work. I filmed and recorded a beautiful scene.

This initial shift led to others. The members of the Band were called on regularly and other home visits awaited them. Why not keep following them? Restoring souls, repairing objects. A third film? Of course, this meant seeking additional funding, but for the rest, if I got organized… I began to believe in it. The three films would form a whole while remaining independent of each other: one could be seen without the other two. Three films within the same psychiatric department, each one of which would raise the curtain on a specific aspect of this psychiatric care that, despite the surrounding devastation, still strives to give priority to human relations. Each film would introduce new faces and reunite us with others.

Press kit

This film is the second part of what will eventually be a triptych. How does it connect with On the Adamant?

At Averroès & Rosa Parks is an extension of the first film. It’s a little as if, after having filmed the stage, this time I was showing the wings and basement. The atmosphere at the hospital is clearly not the same, the place is much starker and the patients who have ended up there are going through a period when they are more vulnerable, shakier. This is clear in the tone of the film, but it’s the same psychiatric care, or rather what remains of it: a form of psychiatry that still strives to take into consideration people’s words when the whole system, increasingly taken over by neurosciences, protocols, experts and evaluation scales, tends to crush that by banking on medication and nothing else. Today, hospitals are in the hands of managers, everyone knows that. They have to increase turnover, reduce the number of beds, shorten as far as possible the length of hospitalization and cut jobs… even though many professionals are leaving of their own accord, unable to find meaning in what they do anymore. The film refers to this situation at several points: a young patient mentions it, the question arises in a meeting; it is there, in the background, but that doesn’t necessarily make this what you could call a “militant” film. Or if there is a militant side, it is working in favour of a certain dignity.

Bringing a camera into a psychiatric hospital is far from commonplace. How did you go about it?

I was not starting from nothing. As my filming on the Adamant had gone well, I benefited from a favourable opinion. The carers had heard good things from their colleagues who move between the two settings and from the patients who frequented it. Some of them knew my films, notably Every Little Thing, the film that I shot at the La Borde clinic in 1995.

I began by filming a little at “the bar”, the library and the newspaper workshop, three appointments that mark out the week. I already knew most of the carers organizing them as nearly all of them work on the Adamant. There’s not a lot of those sequences left, but they helped me to launch the shoot. Some patients agreed to be filmed, while others didn’t. There was nothing surprising about that. One man occasionally burst into the frame making totally surreal comments. He insisted that I film him, he would soon be famous, no doubt about it, he’d show us! It was tricky. How could I avoid upsetting him?

The majority of the film is based on interviews. What led you to make that choice?

That was my idea from the beginning. The interviews and, in second place, the “carer-patient” meetings. I wanted the film to be a host of interrogations. I wanted to open it up to the speech of the patients, their words, their suffering, snatches of their story, to what afflicts, assails, encloses, agitates or terrifies them. This porosity that exposes them to the violence of the world, that strikes them with its full force. The lucidity and acuteness with which they talk about their inner world. The insatiable quest for meaning that torments them. Their hopes, their potentialities, and their humour at times.

If mental sickness is a pathology of connection, filming interviews seemed to me to be a good way to show how the carers try to accompany those who suffer from them and to forge with them the support structures that will help them to get back on their feet, make a new start, forge a connection with the world if not with themselves and reinsert themselves within the social fabric. It would show how accepting each one’s specific words is a painstaking task, always on the edge, very hard to refine.

In On the Adamant, the carers were just as present, but that presence was more discreet. They were all the more so because the film did not designate them as such in an explicit manner. A certain haziness remained, rich in meaning. As the distinction between carers and patients was not underlined, the audience was obliged to rid itself of certain clichés. Here, the situation is different. The face-to-face set-up clearly shows who is who. The therapeutic goal is instantly legible whereas it could seem less focused on “the boat”, at least for someone outside this world.

The interviews that I filmed present a great deal of diversity. I played a lot in editing on the film’s construction and rhythm. Linear at times, disjointed, uneven and zigzagging at others, they do not all advance at the same pace, nor do they have the same duration or the same tone. Some are fluid while others go nowhere. The personality of the patients and the diversity of the situations that they are going through clearly have an important role to play, just like the way in which the carers interpret what they say, each with his or her own style, references, occasional automatisms, way of being with them, of letting the words come and of orienting the conversation or not.

How was this idea of filming the interviews received?

Nearly all the psychiatrists were for it, as long as each patient was too, of course. We talked about it ahead of filming and I relied on their opinion. With some patients, it was maybe not the right time. We would see later. With others, yes, why not? On a practical level, it was often a little acrobatic. The psychiatrists were run off their feet. And then, all of a sudden, they were free for a moment. But the patient had to be free too, or at least feel up to it and we needed to find a room to film the interview, as the psychiatrists do not have individual offices. We barely had the time to set up. There were three of us. Two cameras, a mic on a stand, another at the end of the boom and we were ready to go.

Where the patients were concerned, there were some refusals, but fairly few in the end. The people that I approached were those with whom I had an exchange, a minimum of complicity. I didn’t offer to film those who seemed to me to be going through extremely intense situations, whose words were incoherent, or indeed unintelligible, often transformed by medication. It would have meant filming them without their knowing it. And to their detriment. Filming someone always means enclosing them, freezing them in time and space. Imprisoning them. You must therefore strive to avoid doing any harm. I wanted them to be in a position to accept the situation “in all conscience”. But that notion itself is a little vague. When someone is raving, having hallucinations, or is haunted by voices for example, that is not necessarily visible. Do we always know what is going on in our minds? Even with the best intentions, we never know what the camera might do to people.

The film does not specify the professional status of the carers conducting these interviews.

That’s true, but I couldn’t imagine myself putting their names and professions on the screen, like on TV. In that case, why not put the patients’ names too? Everyone who appears in the film is named in the credits, but that is not the same. To answer your question, three of them are psychiatrists. A fourth, in training when I was filming, has become one since. The young female carer was doing a medical internship at the centre . Finally, the woman who appears in tandem at two points – first with one psychiatrist and then with another – is a social worker.

Usually, a nurse, male or female, takes part in these interviews alongside the doctors, but we had to give up on that as it was so complicated to get everyone together at the same time. In addition, other professionals like psychologists do their own interviews but I couldn’t increase the number of protagonists as there are already so many. Everyone knows that a film is not exhaustive.

You also film meetings…

Yes, I was especially keen on filming the Tuesday “carer-patient” meetings that allow for all subjects to be tackled freely without a prior agenda. Their slightly anarchistic aspect would break up and jostle the ritual of the interviews and the editing itself. These scenes testify to the daily life of the hospital, of the climate that can reign there, of the desire that the team of carers has to share time thinking with the patients, but these are only brief moments. From one week to the next, these meetings are very different. The greenhouse, with its plants, its armchairs and its bookshelves, is the lung of the two units.

In this film, you don’t adopt exactly the same position as on the Adamant. You stand a little further back.

Yes, that’s true. In On the Adamant, the patients spoke to me a lot whereas here, apart from one interview, they speak to the carers. Even so, I’m not absent. The numerous looks at the camera testify to my presence and even, here and there, to a certain complicity.

Let me return to the idea of speaking and listening. In your films, whatever world they tackle, this dimension is extremely present and you show it in many ways.

My own relationship to language is far from simple. My way of speaking has never been very fluid. I occasionally begin to speak and, all of a sudden, the words don’t emerge. I don’t know if there’s a connection, but I have always liked filming speech, which is perhaps in my eyes the most precious thing we have. Yet I have the feeling that it is increasingly devalued. This is not only true in the psychiatric world. In the field of documentary cinema, filming speech is not very “trendy’. We are living in a strange world, where we are all “connected”, where we have never communicated so much… and spoken so little together.

Filming speech means filming faces, looks, expressions, gestures, silences, laughs, hesitations, shortcuts, associations, extrapolations, ways of occupying space and opening up new ones. It means bringing to the fore everything that colours or sharpens ideas. It means filming that share of fiction inherent in every tale, since speaking is not only relating the real world, it is also and always a way of reshaping it and reinventing it. Relating something that never happened is what allows it to exist. Speech is the realm of fiction.

After Every Little Thing and On the Adamant, this film is your third in the world of psychiatric care, and there will shortly be a fourth one (1). What incites you to return to it?

Psychiatry is a magnifying glass, an enlarging mirror that says a great deal both about the human soul and the state of a society. You meet all kinds of people who have suffered, fragile and sensitive beings who move through life as if walking a high wire. In talking to them, they can force us to face home truths, drive us into a corner, or lead us into lands where we never thought we’d set foot. It took me time to admit it to myself, but if these people touch me so much, it’s because they force me to face myself and my own vulnerabilities.

(1) The Typewriter and Other Headaches, French release planned for April 2024

The Hollywood Reporter - February 16, 2024

French director Nicolas Philibert follows up ‘On the Adamant,’ which won Berlin’s Golden Bear prize last year, with another deep dive into a psychiatric facility.

Plenty of worthy documentaries manage to tackle a subject from all angles, offering a well-rounded portrait of a specific social issue, historical figure or cultural phenomenon. Much rarer are those that go beyond the subject to reveal something deeply and essentially human, using the camera to uncover truths that aren’t always visible to us.

French director Nicolas Philibert’s latest work, At Averroes & Rosa Parks, is one of those films. On the surface, it’s a long and immersive plunge into two psychiatric wards at the Esquirol Hospital facility, located in a leafy suburb outside of Paris. Through extended sessions between patients and their doctors, we get to know a group of people who’ve been committed with varying levels of mental illness.

By giving the patients considerable time and space to bare themselves before the camera, Philibert grants us access to the the darker sides of the human psyche, portraying mental illness with an innate sense of compassion and understanding. We wind up empathizing with the patients because we see them as people, not just as patients. And we catch a rare and very real glimpse of the thin line that sometimes separate us from them.

The second part of a triptych that began in 2022 with On the Adamant, a portrait of an art therapy center on the Seine in Paris, At Averroes & Rosa Parks follows some of the same people we met during that movie, though this time while they receive more direct treatment. Using a fly-on-the-wall approach that recalls the work of Frederick Wiseman, as well as fellow Frenchman Raymond Depardon — whose 2017 doc, 12 Days, was also set in a psychiatric hospital — the film consists of several one-on-one or group therapy sessions, intercut with shots of the patients wandering the grounds of the facility.

Like in his other movies, including the 2002 schoolhouse chronicle, To Be and To Have, Philibert served as cinematographer and editor, and he has a particular gift for capturing life without seeming to interrupt it. Here, the patients speak freely and willingly to their psychiatrists as we look on, describing symptoms of depression, paranoia and other, more severe disorders. Almost all of them want to “return to the reality of life,” but they’re not all able to do it. They grasp what their problems are, sometimes quite acutely, but that doesn’t mean they can overcome them.

“I want to make it whatever happens,” says one hopeful patient early on, though he never seems to leave the facility afterwards. Another patient — a brilliant philosophy teacher with several PhDs — quotes from the writings of Aristotle and Nietzsche, describing himself as a “metaphysical chameleon.” And yet his superior intellect doesn’t prevent him from remaining in the hospital for several months — a fact he attributes to a bad LSD trip when he was young, claiming that he “paid a high price to see god.”

Even those barely able to communicate — including an older woman who tragically sets herself on fire toward the end of the film — manage to convey something about their conditions, guided by a handful of doctors armed with an extreme level of calm. When they speak to the patients, they can be blunt, playful, clinical and disarming all at once. Most of all, they have a sharp sense of observation and an openness to the human suffering they encounter, which are qualities Philibert seems to possess as well.

At Averroes & Rosa Parks doesn’t reveal any groundbreaking solutions to the patients’ disorders, but rather shows how a mix of therapies can provide comfort and eventually, a way out. The doctors try as much as possible to integrate their patients into real-life situations, whether it’s buying coffee in a makeshift café or participating in politically charged group discussions about their healthcare situations. The more the patients are treated like normal people, the more, it seems, they act normally.

In the film’s opening sequence, which features overhead footage shot with a drone, someone describes the Esquirol complex as a typical example of neoclassical architecture used for “jails, hospitals and prisons.” There are times in Philibert’s movie when the facility can indeed resemble all three of those things. But most of the time, it feels like a place where everyone, even the most blighted, can have their say.

Screen Daily - February 16, 2024

Veteran documentarian Nicolas Philibert brings his focus to the Esquirol Hospital in Saint-Maurice near Paris; in particular, two psychiatric units named after the Islamic philosopher and mathematician Averroes and American civil rights icon Rosa Parks. The second in a projected trilogy following last year’s On The Adamant, it is a more austere film, its energies much more introverted – with contents that, at times, are altogether harrowing.

An extremely accomplished and compelling work

On The Adamant deservedly won Berlin’s Golden Bear, surely in part because the film was so uplifting: an affirmative, compassionate depiction of a Parisian mental health facility and its patience. Celebrating an enlightened, culture-based approach to psychiatric care, On the Adamant was in the best sense – if such a thing is imaginable – a feelgood film about mental illness. At Averroès & Rosa Parks, which premiered in Berlinale Special, is a tougher watch than its predecessor, but an extremely accomplished and compelling work, the latest chapter in a formidable documentary career that includes such works as Etre et Avoir and 1997 psychiatric clinic study Every Little Thing.

The film begins with a panoramic drone shot scanning the grid-like construction of the vast building, with a staff member watching the footage and noting that, like so many French institutional buildings of the period, it resembles a prison; indeed the edifice, originally built in the 18th century, dates from a time when mental institutions were indeed more akin to prisons.

Where On The Adamant highlighted the collective cultural activities of a day centre on the Seine, this sequel largely comprises a set of consultations between staff members and resident patients (some of whom are soon to be discharged, and who are advised by doctors to use the resources of the Adamant). Philbert’s unobtrusive camera typically keeps to a shot-reverse-shot pattern in medium, with the occasional close-up; one sequence has a woman apparently talking to someone behind the camera, but the film largely maintains its observational detachment, listening in on the patients’ accounts of their experiences, and the doctors’ questions and comments.

If On The Adamant came across as a set of fascinating character studies, the detachment of its sequel offers more of an inventory of varieties of mental illness. The dialogues between patients and carers – who come across as eminently empathetic, albeit to varying degrees – reveal the kind of stresses and challenges faced by mentally ill people both in the wider world and within the psychiatric system into which they are often painfully aware of having been absorbed.

Among the people we meet are Monsieur Obadia, about to be discharged, who is being offered temporary shared accommodation in the city, but whose concerns – about his own religious observation as a Jew, and about the French government with its policy of secularity – leads him to counter every suggestion with anxious objections. Then there is Olivier, a young man with learning difficulties, who is confused about his family relations, convinced that other people’s daughters are his and that his dead father and grandfather are present at the hospital in the form of other people (although at the same time, he seems fully aware of everyone’s real identity).

If there is an individual in this film who particularly fascinates, it is middle-aged Noé, first glimpsed making brief comments in a handful of group discussion scenes. Towards the end of the film, Noé has an individual meeting with two staff members and explains his history as a Jewish Buddhist, an idealistic higher education teacher suffering from burnout, a dissenter from the French academic system, and a self-confessed “megalomaniac” and “metapsychic chameleon” who identifies very closely with the thinkers he reads (“I became Nietszche”). Not that this is Philibert’s intention, but Noé, like several regulars on the Adamant, could easily have been subjects of entire features.

While the extended Noé sequence might have made an uplifting conclusion – showing mental illness in a particularly vibrant and, it seems, creative form – Philibert refuses us obvious consolations by following it with the second of two sequences with a profoundly troubled, angry elderly woman named Laurence. This give the film a decidedly different inflection, revealing the extremes of mental suffering in a bleakly realistic fashion. These sequences, however, also raise thorny questions of consent and intrusiveness; similar issues were raised back in 1967 by another mental institution documentary, the controversial Titicut Follies, by Philibert’s kindred spirit Frederick Wiseman.

As well as the odd briefly-shown group meeting and activity, punctuating shots show the corridors and courtyards of the Esquirol Hospital, including the monastic-looking cloisters that are traces of the building’s less enlightened early days. Aalthough this is never commented on, the hospital was formerly known as the Charenton asylum, in its day housing such eminent patients as the poet Verlaine and the Marquis de Sade.

The Guardian - 17 July 2025

Laurence is a woman in desperate need of an act of human kindness. The grey-haired patient urges her psychiatrist for a hug, a cuddle – that, she says, is all she needs to keep at bay the nightmarish visions that haunt her. Yet on her ward at the Esquirol hospital centre in Paris, such simple gestures are impossible to come by. “When I asked for a hug,” Laurence laments, “they gave me a jar of yoghurt.”

This scene, from Nicolas Philibert’s new documentary At Averroès & Rosa Parks (two sections of the Esquirol hospital centre), is as hard to watch as anything you are likely to see on a cinema screen this year. But it is especially remarkable coming from perhaps the world’s pre-eminent maker ok humanist documentaries. The Frenchman Philibert is one of modern cinema’s great champions of kindness. Aged 74, he has built a career making award-winning observational portraits of places that excel at giving care within a hostile modern world: a southern French school for hearing-impaired people in 1992’s In the Land of the Deaf; museums and the people who dedicate their lives to maintaining the objects inside them in Louvre City (1990) and Animals and More Animals (1995); a single-teacher infant school in the rural Auvergne region in Être et Avoir, his 2001 international breakthrough film.

On the adamant, his 2023 Golden Bear-winning doc about an occupational therapy centre moored on the river Seine, was Philibertism par excellence : a film about a place that heals because it lives up to the simple ideal of treating patients as people. Yet its follow-up – which explores where some of the Adamant’s passengers go on their bad days – is a film about a place where healing never seems to take place.

“[For] On the Adamant, I filmed a lot of workshops and group meetings,” Philibert says on a video call from Paris. “In At Averroes & Rosa Parks, the atmosphere and architecture is more severe, the space is more constraining. When the patients are in the hospital, they are more vulnerable, they are more in pain, they are overwhelmed by anxieties. Life is a hell. Everyone is locked in their solitude.”

The film about the floating daycare centre became a crowdpleaser because it managed to portray a potentially forlorn place as something more akin to an elite institution for outsider artists (its name, riffing on that of the English post-punk singer who has been open about his bipolar disorder, is no coincidence). But during the filming Philibert realised: “If I didn’t show that the patients circulate between the boat and less prestigious structures, I wouldn’t be showing reality.” The result is what he calls a “triptych” of three films shot over a 12-month period between April 2021 and 2022, screening for the first time in their entirety in the UK at London’s Bertha DocHouse cinema next weekend.

The third of the three films, The Typewriter and Other Headaches (Philibert says they can be watched in any order), is still infused with its director’s typical humanism: following the Adamant’s carers as they visit their patients at home to repair broken typewriters, printers and record players, it shows how broken machines and severed links to the outside world can be fixed.

And if we do not see any repair work in At Averroès & Rosa Parks, it’s not for the carers’ lack of trying. Made up entirely of conversations between mental health patients and their psychiatrists, it shows the hospital’s staff display extraordinary empathy in their handling of people with severe conditions. We hear them engage respectfully with Olivier, who is confused about family relations and tells his carers that other people’s daughters are his, and that his grandfather is present at the hospital in the shape of other patients. We see them listen patiently to Noé, who speaks multiple languages, makes art, practises Buddhism, teaches philosophy, but also suffers from “megalomania”, a condition he believes was brought on by swallowing a handful of acid at a trance festival as a teenager.

But there is always a lurking sense that these conversations are under strain. One patient, Pascal, tells his carer that great psychiatrists are like Kylian Mbappé, the French footballer known for his clinical finishing: “They get to the point, they sense things.” But when he lists the names of psychiatrists he considers top of his league, he pointedly omits to mention the woman he is talking to, and then phases out of the conversation completely. Laurence’s psychiatrist goes to extreme lengths to assuage her fear that the carers are out to harm her and steal her cigarettes, but she snaps back: “I don’t trust you, I stopped trusting you ages ago. You’re dumb, you’re dumb as shit.” He doesn’t retaliate – there’s a camera rolling, after all – but can’t quite stop the hurt pride from showing on his face.

“I really wanted for this second film to be based almost entirely on speech and listening, because these are two things that almost becoming extinct in the psychiatric world,” says Philibert. “Public hospitals in France and elsewhere are becoming abandoned by public power. It translates as a deep lack of means, a deep lack of attractiveness. A lot of nurses who work in psychiatry end up leaving because they can carry out their work with dignity less and less.”

At the end of the film, we meet Laurence again. Her flowing locks have been trimmed short, and she has bloodied plasters on her fingers and festering burns on her face. In a moment of desperation, we learn, she set herself on fire. I wonder if that last scene comes close to violating one of the principles Philibert’s previous films adhered to: for all his interest in people with mental troubles, he usually goes to some lengths to avoid showing them in their troubled state. Yet his depiction of Laurence could be seen to be using her pain for dramatic effect.

Philibert is quick to reassert his ethical guidelines. “My films rest on trust,” he says, adding: “Even if a patient or a carer signs a written authorisation, it doesn’t mean that you’re immune or that legal pursuit isn’t possible if you tarnish the image of a person.” He’s speaking from experience: after Être et Avoir became a breakout hit, the teacher at the heart of the film (unsuccessfully) tried to sue Philibert for a share of the profits, claiming that the film’s success rested entirely on his personality.

In Laurence’s case, Philibert insists that she gave her consent before and after the filming, because she perceived his request “a proof of consideration”. “‘You want to film me? Oh, you’re interested in me. Me who is always sidelined, rejected, made invisible.’”

Still, it’s fascinating to watch a film-maker discover new emotional timbres in his 70s. When the screen cuts to black at the end, and a jazz-guitar version of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy plays over the credits, it feels like we are encountering a very unlikely emotion for a Philibert film: bitterness. And perhaps he is also allowing his beliefs to shine through more than previously. In the film’s opening scene, when staff and patients watch drone footage of the hospital, Noé comments: “It’s scary, it’s like a prison.” Philibert is fond of quoting his fellow documentarian Frederick Wiseman’s maxim: “If you need to drive home a message, send an email but don’t make a film,” but what is this if not a pointed message about the state of modern French psychiatry?

“You know, the world of psychiatry is the realm of the unexpected,” he says. “When you enter, all your certainties are shattered. The madmen reset all your counters to zero. They push you to revise all your diagrams.”

-

On the Adamant, The Typewriter and Other Headaches and At Averroes & Rosa Parks are showing at Bertha DocHouse 26-27 July (2025)