Christophe Profit’s “100% solo” climb (without ropes and without belays) of the west face of Les Drus, a gigantic, 3,600-foot vertical pyramid in the heart of the Mont-Blanc range.

Christophe Profit is one of the greatest mountaineers of his generation.

Based on an idea by Yves Ballu

Photography Laurent Chevallier, Amar Arhab, Didier Lafond • Sound Bernard Prud’homme • Still photography Vincent Mercié • Machinery Dominique Legueux • Assistant director Suzel Galliard • With the technical back-up of the guides Michel Arrizi, Charles Daubas, Jacques Fouque, Alexis Long, Pierre Mailly, Dominique Radigue, Sylviane Tavernier, Jean-Paul Vion, Jacques Wintenberger, the helicopter pilot Didier Biren and his co-pilot Jean-Paul Merigeaud • Editing Marie Quinton • Original score André Giroud • Production manager Alain Lacour • Producer Jean-Pierre Bailly • Produced by La Maison du Cinéma de Grenoble • With the participation of Antenne 2, Alpa and Sandoz-France.

Grand Prize, International Adventure Film Festival, La Plagne, 1985 • Gold Diable and Cinégramm Award, International Alpine Film Festival, Les Diablerets (Switzerland), 1986 • Grand Prize, Teplice Nad Metuji Festival (Czechoslovakia), 1986 • Third Prize, International Mountain Film Festival, Graz (Austria), 1986 • “Best Mountain Film”, Banff Mountain Film Festival (Canada), 1987 • Best Mountaineering Film, International Mountain Film Festival, Torello (Spain), 1987.

First TV broadcast : February 1986 / Antenne 2.

On the west face of Les Drus by Nicolas Philibert

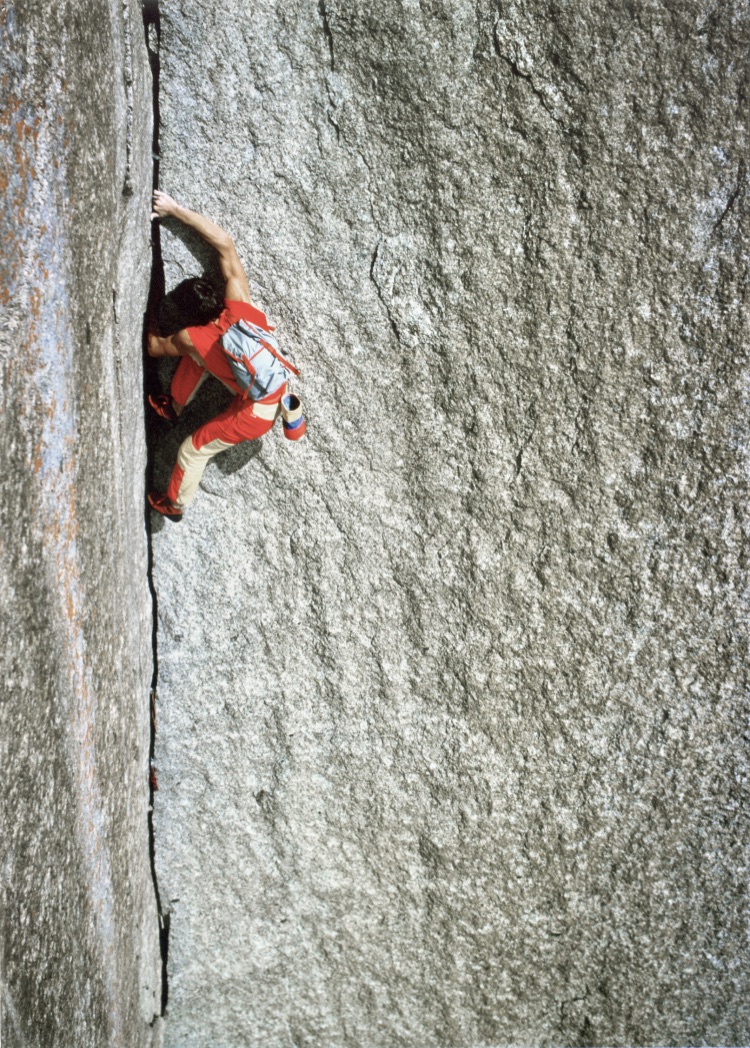

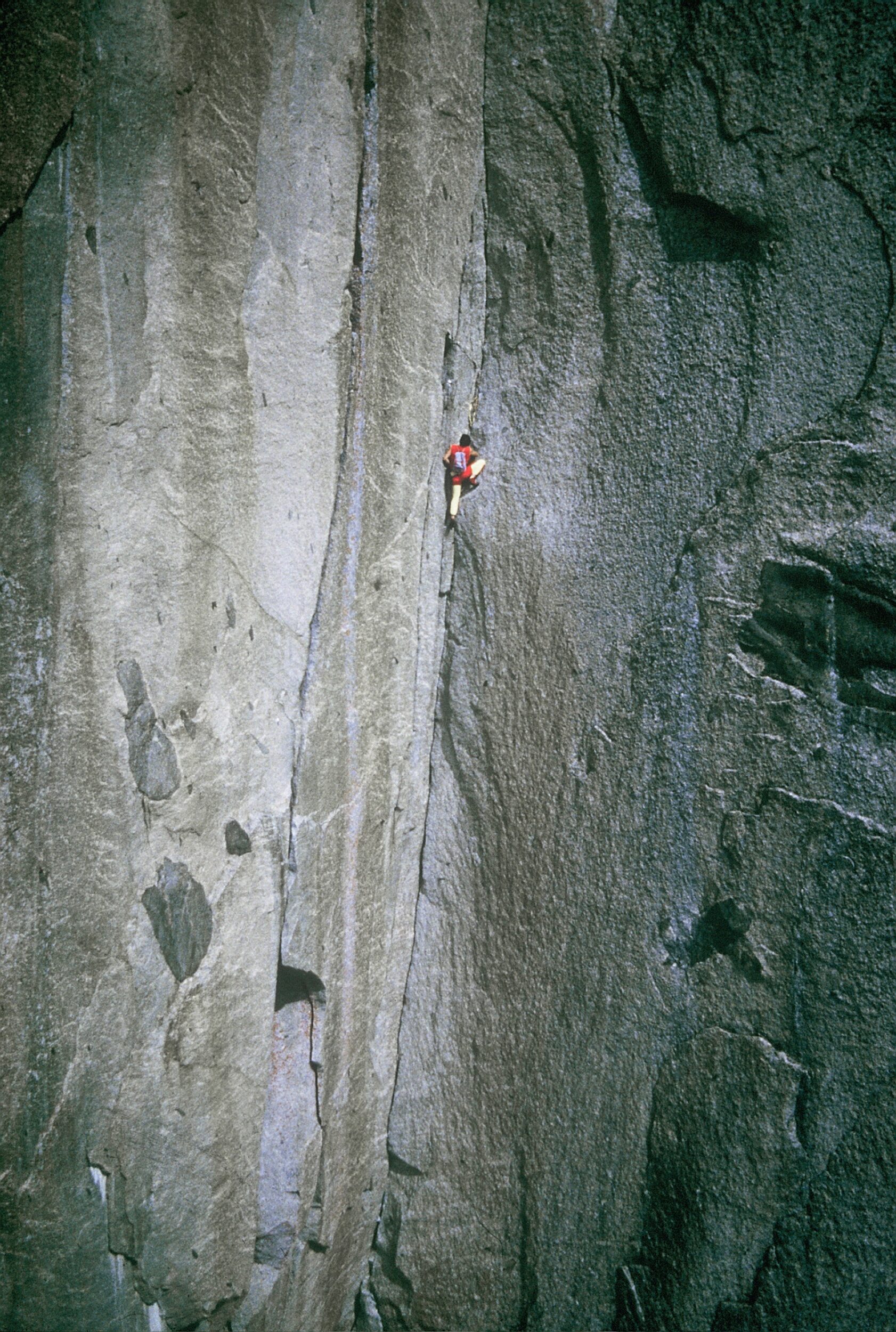

In late 1984, when I was offered this film (a different director was originally slated to shoot it), I hesitated a great deal. The task was to film the young virtuoso mountaineer Christophe Profit in the solo ascent of the west face of Les Drus in the heart of the Mont Blanc range, a gigantic, vertical and smooth granite wall 32,0000 feet high, interrupted by huge overhangs. I had absolutely no experience of shooting in such conditions and, even though I had done a little climbing during my adolescent and student years, I had never attained a level that would have allowed me to attack a face of this scale. Moreover, it was a good ten years since I had last been in the mountains. On the other hand, I hadn’t shot anything since La Voix de son maître (His Master’s Voice), in 1978. All my personal projects were on hold and I was getting nowhere…

Three years earlier, Christophe Profit, aged barely 21, had found fame by carrying out this extremely difficult climb “100% solo” (without ropes or belays) in the amazing time of three hours and ten minutes when the best climbing teams needed a day and a half to complete it. This feat earned him the nickname of the “Summit Sprinter” and won him an immediate place in mountaineering history. The film therefore appeared as the rerun of this extraordinary feat that it would be necessary to shot not in real time but in short sequences over several days. There was a slight fiction element, a vague story that acted as a pretext and that I found fairly naïve, but I had no choice: it was take it or leave it! To cut a long story short, after a sleepless night, I accepted the commission.

Shooting on the rock face required rigorous organization that would not brook the slightest hesitation. The timing and the cost of the chopper flights, the dangerous nature of the drops, the size of the crew (with the guides, one for each of the twelve members of the film crew), the complexity and slowness of our movements, the rope manoeuvres, the manipulation of the film equipment, each element of which had to be roped up to prevent it from falling into the void at the first false move, not to mention the risk inherent in every high mountain climb – falling stones, the unexpected arrival of bad weather, falls or accidents – conferred an epic dimension on the whole undertaking.

For each of the key moments in the climb, the positioning of the two cameras was the object of lengthy preparatory discussions with Christophe, Sylviane Tavernier, his partner at the time – who would become the first woman to join the prestigious Chamonix Guides Guild a few months later – and Dominique Radigue, another young and extremely brilliant climber with whom Christophe often formed a team when he wasn’t climbing “solo” and who would go missing the following year on the slopes of Aconcagua. These discussions were soon shared with the guides that we had hired and whose cool heads would prove precious throughout shooting. In turn, I had done a little scouting by helicopter and had even climbed the first third of the face with Christophe and Dominique, up to the famous “45-metre fissure” that, to my great pride, I had managed to cross without ropes and belays.

Laurent Chevallier, behind his camera, was a peerless photographer. He filmed instinctively, with an incredible sense of framing. He had already shot a number of mountaineering films and allowed me to profit from his experience. The head of the second unit, Amar Arhab, was also extremely imaginative but, unlike Laurent, he had never done any mountaineering and tried to dispel his fear by cracking endless jokes. As for Bernard Prud’homme, he was the epitome of discretion. Both a sound engineer and a mountain guide, the acting chairman of the Chamonix Guides Guild, with his more than six-foot frame he gave off an incredible impression of strength and invulnerability.

Each morning, the helicopter would drop us on the face at a different spot, painstakingly scouted and “equipped” by the guides, the equipment in question consisting of a few expansion pegs that we could hang ourselves and our material from without any worries. In several spots, the guides had also left, safe from prying eyes, packs with space blankets, drinks, food and first-aid kits in case bad weather forced us to bivouac on the face.

The drops were moments of extreme tension. However skilled our pilot was, the closer we got to the rock face, the greater the risk. We never really dared to talk about it but each one of us knew that the slightest fall of rock on the chopper’s blades or a sudden gust of wind would have disastrous consequences. To carry us all up to the shooting location, no fewer than four trips were required from the DZ (dropping zone) in Chamonix, and a fifth one was required for all our gear. In some cases, the sheerness of the rock face prevented the chopper from getting close. We then had to be winched down to a spot higher up the face, or be dropped on the north face that is not as steep, and get to the planned spot by belaying or crossing the face. These operations were very impressive. The helicopter would hover, its blades spitting at times just three feet from the face, creating a terrific din and risking loosening rock at any second. Each in turn, we had to move to the outside of the craft, stand on the runner, gently pass the line of the winch through our harness, “sit down” in the void and let ourselves be lowered thirty or forty yards until reaching a minute ledge were a guide would grab us tightly and hook us up to the nearest piton. Later, I was shocked to hear the pilot tell me that, if ever there was a problem, he would just need to pull on a lever to cut the winch cable and sacrifice the man at the end of the line by dropping him. A good job he never needed to do it!

Once the whole crew was on site, we started to take up our positions, with each one of us moving to his assigned spot. This could take another two hours. Finally, we called Christophe by walkie-talkie. He would then take the chopper and join us up there.

During the first few days, he would cover one tough section after another with such ease that it was unsettling. Of course, seeing him alone without a rope, lost on the vast face three times higher than the Eiffel Tower, where the slightest mistake would lead only to a fatal fall, was a pretty impressive sight… However, if he climbed so nimbly, that meant it couldn’t be that complicated! How could the audience perceive the difficulty of his undertaking?

But the ascent of the famous “90-metre dièdre” would soon reveal his feat in its full dimension…

I can still see Christophe in the middle of this terrifyingly tough section, totally smooth and overhanging, split by a narrow crack along its middle. Even though he has 2,600 feet of space beneath his feet, this doesn’t seem to bother him, he carries out his movements with extreme precision. But, all of a sudden, he stops, hesitates, looks for his holds… He tries again but no, it’s clearly not working! Quick, he can’t stay there like that! Quick, quick, he’s not going to last long! Tension is at a peak. A few yards away from him, a little further up on the left, we are powerless to help. All of a sudden, gripped by a surge of adrenalin, he starts screaming, insulting the mountain, and begins to climb back down a few yards, reaching out blindly with his leg, feeling around with his foot for the tiniest ridge. If ever it doesn’t hold… but it holds! Then the other foot and so on… At last, he reaches a minute knob of rock, the tip of each foot resting on just a fraction of an inch, his hands bolted into the crack. Quick, we throw him a rope, he ties himself too it. Phew! What a relief. Those three minutes lasted a lifetime!

Later, during editing, I insisted on keeping this sequence. Christophe wasn’t too keen on the idea. He was afraid it would harm his “image”. But he would end up coming round to my way of thinking: more than any other, this scene would allow the audience to measure the scale of his feat and would give the climber, suddenly vulnerable, a “human” side that he wouldn’t have had without it.

Today, the appearance of the west face of Les Drus has changed significantly. In 1997, then in 2003, and again in 2005, a series of rock falls affected the structure of the mountain and destroyed a number of historic routes, offering climbers a brand-new mountain. But it will no doubt be years before the rock stabilizes.

An original score, an absence of commentary, a simple but effective screenplay and, above, all, breathtaking images! Directed by Nicolas Philibert, this short film’s key merit, in a genre renowned for its patchiness, is to find the right tone, form and content. It clearly shows the total physical commitment and the dimension of the feat. We feel the intensity of the event, especially as a dramatic note is there to underline the risk of a fall while the comical conclusion eases the atmosphere and reminds us that Christophe climbs for his own pleasure.

Jean-Paul Roudier, Le Dauphiné Libéré, november 9, 1985

……………

The cinematic event of the mountaineering year. Profit on the big screen for the first time. With discretion and sobriety. A sensitive film that breathes new life into mountaineering cinema. A soundtrack that doesn’t wallow in the climber’s emotions. No meaningless dialogue. The rhythm of an unobtrusive original score. Two messages of friendship and the simple sound of Christophe’s breathing tell us the whole story.

Isabelle Fortis, Montagnes Magazine, december 1985

……………

In front of the camera, Christophe Profit is going to carry out the ascension of the west face of Les Drus. And, as usual, this is a 100% solo climb: barehanded, without ropes or pitons. At the foot of the face, he changes his shoes… for lighter ones. And, indeed, his first moves on the rocks have the lightness of a ballet. Then, still with the same incredible lightness, he clings to the smooth, vertical face 32,000 feet high. Hero of these towering, lonely peaks, Christophe Profit occupies the screen alone. With the mountains. Without technical commentary or flights of lyricism, the film respects the climber’s silence and so offers a visual poem that exalts the moral and physical aesthetics of an exceptional feat.

Jacques Renoux, Télérama, February 5, 1986