Every year, tens of thousands of youg people, both girls and boys, embark on nursing studies. Upon being admitted to the nursing school IFSI, Between theoretical courses, practical exercises and internships, they will have to acquire a vast amount of knowledge, master numerous technical skills, and prepare to take on heavy responsabilities.

The film traces the ups and downs of an apprenticeship that will confront them very early, at a very young age, with human fragility, suffering, illness, and the cracks in souls and bodies.

Camera Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Rémi Jennequin, Aurélien Py, Camille Clément, Pierre-Hubert Martin, Cécile Philibert • Sound Yolande Decarsin • Editing Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Janusz Baranek • Sound editor Romain Ozanne • Sound mixing Emmanuel Croset • Colour grading Christophe Bousquet • Production assistant Cécile Philibert • Line producer Cédric Ettouati • Co-producer Norio Hatano • Producer Denis Freyd • Produced by Archipel 35, France 3 Cinéma, Longride • With the participation of Ciné +, France Télévision, and Les Films du Losange, Doc & Film International, Blaq Out, UniversCiné • With the support of La Région Île-de-France, in partnership with CNC, and European Union Europe Créative MEDIA program • With the supervisors and nursing students of the IFPS of the Fondation Œuvre de la Croix Saint-Simon, Montreuil.

This film was made with the complicity of Linda De Zitter.

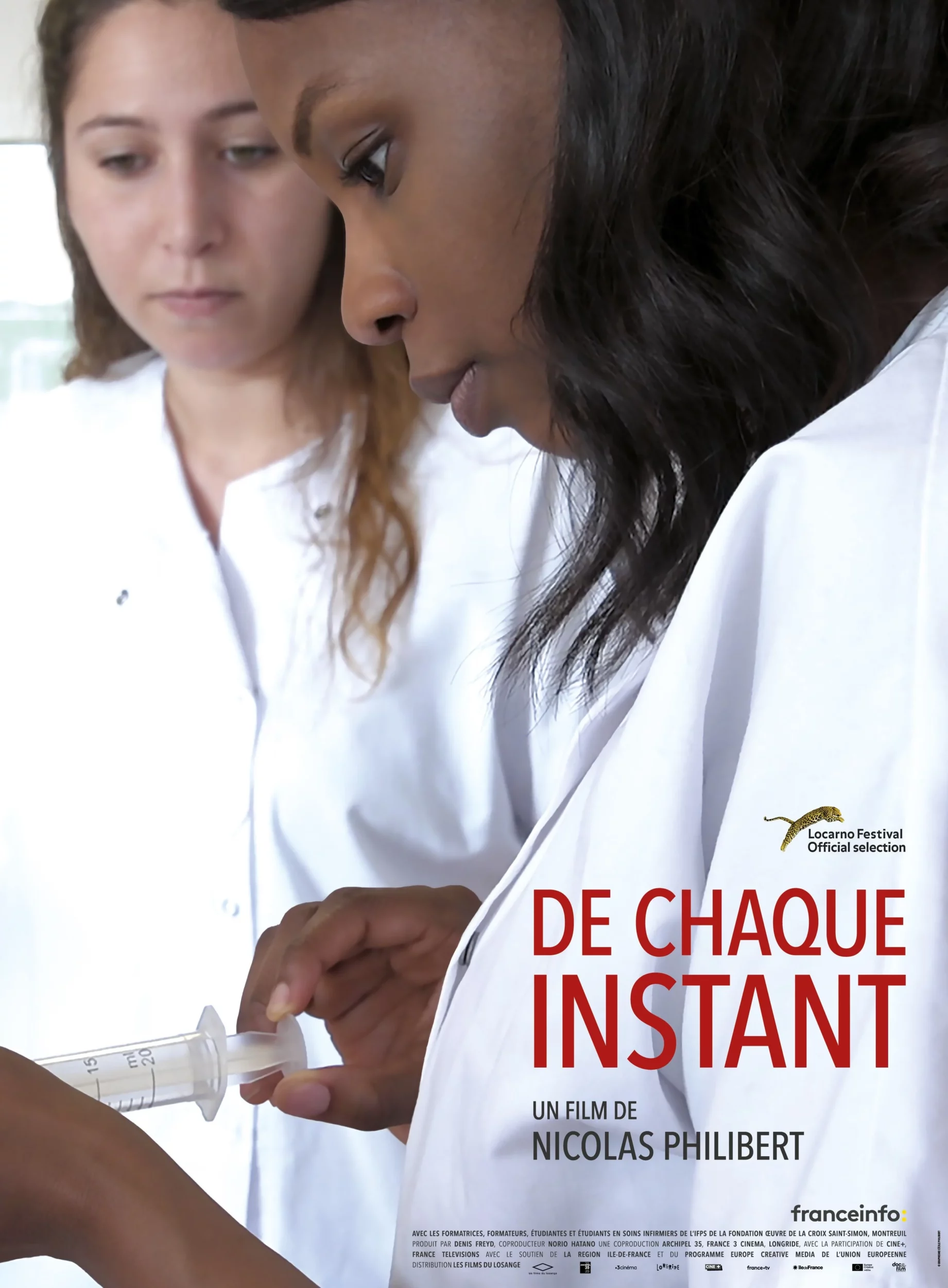

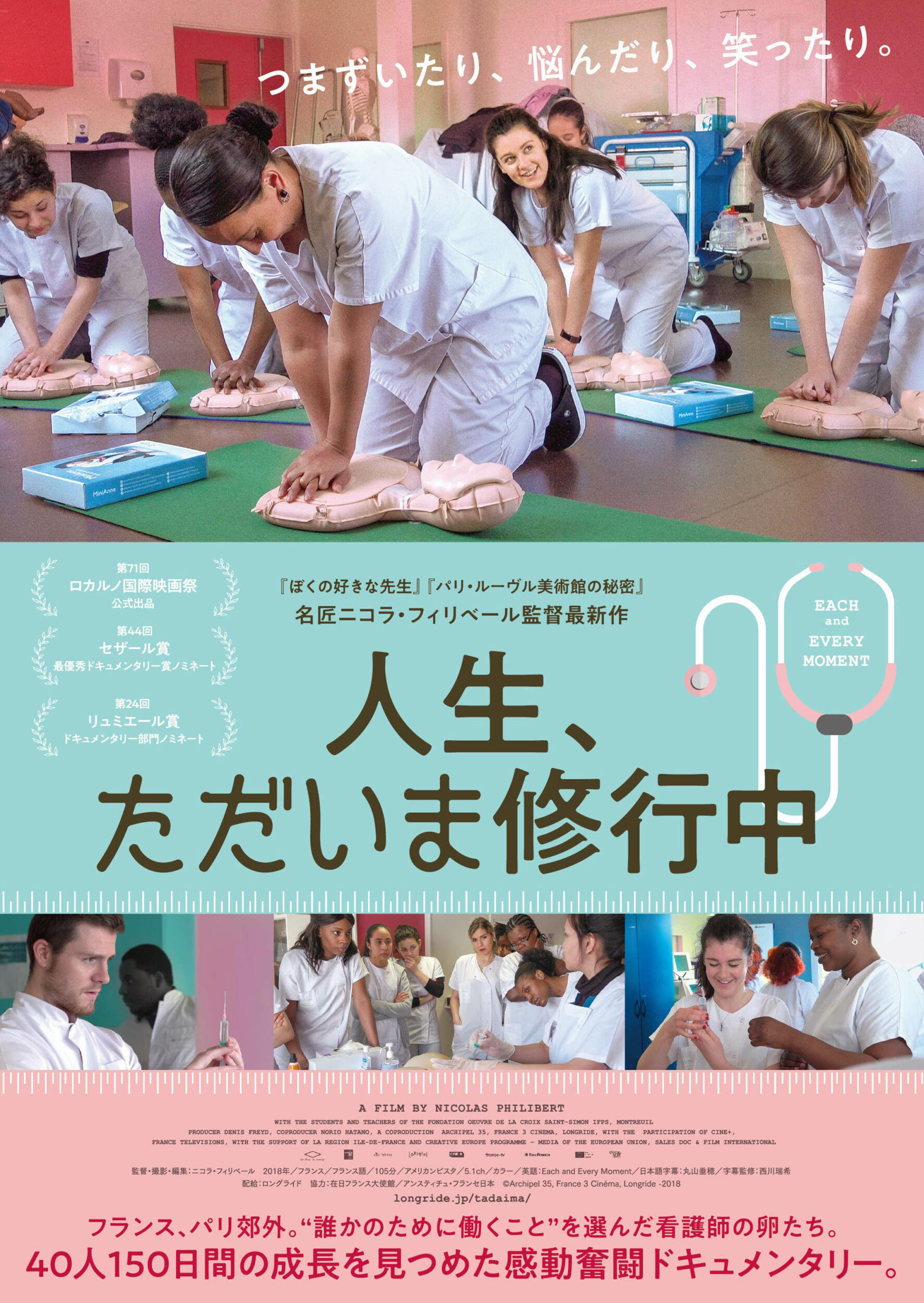

Official selection, Locarno Film Festival, August 2018 • Etats généraux du film documentaire, Lussas, August 2018 • Festival du Film Francophone d’Angoulème, August 2018 • Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia (Mexique), October 2018 • Rencontres Internationales du Documentaire de Montréal, November 2018 • Sevilla European Film Festival, Nov 2018 • International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam (IDFA), Nov 2018 • Filmmaker Festival Internazionale di Cinema, Milano, Nov 2018

International Sales :

The Party Film Sales – sales@thepartysales.com / 331 76 21 51 77

Interview with Nicolas Philibert

How did this project come about?

I had been circling this idea for a while, when Providence sent me to do scouting: in January 2016, an embolism put me straight in the emergency room and then in an intensive care unit. That was the trigger. When I was back on my feet, I decided to make this film, as a tribute to healthcare staff, especially nurses.

Why did you choose to focus on the learning stage? After Le Pays des sourds (In the Land of the Deaf) and Être et avoir (To Be and to Have), what led you in that direction again?

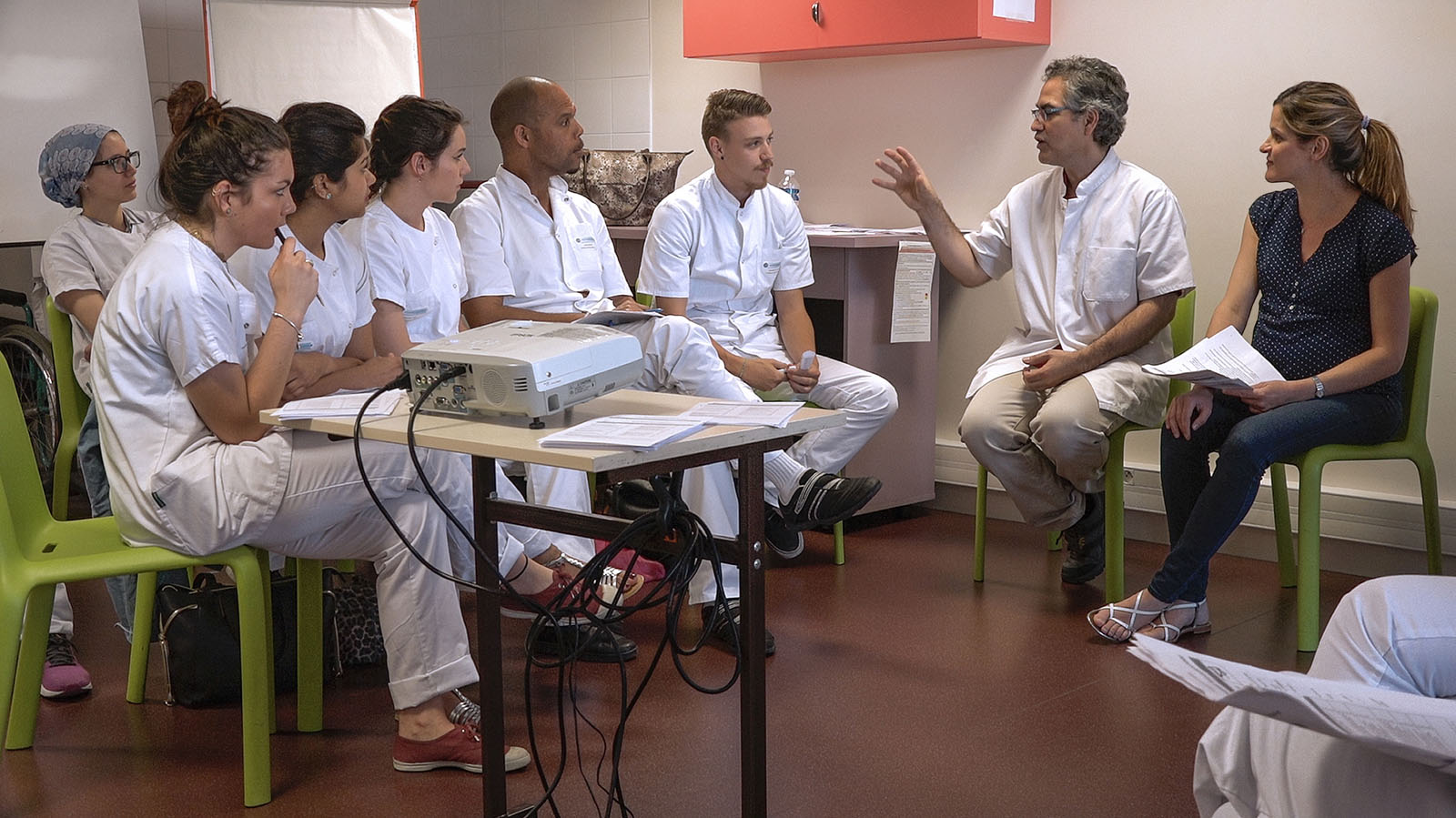

Learning situations allow a director to film the foundations, highlighting what time and experience end up making imperceptible. When you see a nurse performing ordinary treatment, an injection or a blood test, say, it seems quite simple, it’s easy. Unless you’re in that line of work, you cannot imagine all the mistakes that she has learned to avoid, the rules of hygiene, the protocols, the thousand and one little things that dexterity has gradually erased. Filming classes and practical work sessions can be repetitive, funny, mysterious, comical or exciting, things sometimes hang by a thread, but from a dramaturgical point of view, it’s very fruitful. Seeing students grope, make mistakes and start again, following them in their efforts makes them appear closer and more human: will they succeed? How should they have gone about it? And would I be able to do the same? In short, we side with them, we can identify with them. And filming them learning also means filming desire. The desire to learn, to improve. The desire to graduate, to fit into society, to make oneself useful. The nursing profession is difficult, exhausting, poorly paid, often discredited within the hospital hierarchy, and yet it remains attractive and benefits from an excellent image in the mind of the general public. Indeed, this somewhat idealized image is often at the origin of the decision to become a nurse.

What made you choose the Institut de la Croix-Saint-Simon?

I wanted to shoot in Paris or in the inner suburbs, preferably not too far from home, so as not to lose too much time on the commute. I visited six or seven training institutes out of the sixty or so in the Île-de-France Region. The Croix-Saint-Simon team in Montreuil quickly became involved. The great cultural and social diversity of the students also played a role. In these days of retreat into nationalist ideas of identity, I liked the idea of filming young people ready to embark on a career focused on others. And, finally, the Montreuil Institute is a «human-sized» school: there are «only» 90 students per class. As the course lasts three years, that still makes 270 students in the whole sector and, within the framework of a shoot, that is quite a lot, but some institutes welcome three times as many. La Pitié-Salpêtrière in central Paris has nearly 1,000 students! Things turned out this way, but I must point out that the Institut de la Croix Saint-Simon is a private institution «recognized as a public utility». Private does not mean that the students come from a wealthy background. Like the population of the area in which it is located, most of them are from a modest background, and the Île-de-France Region, as well as various vocational training organizations, covers their tuition fees. Moreover, it is a secular establishment. Its name is explained by the fact that at the time of its creation, the foundation on which it depends was located rue de la Croix Saint-Simon, in the 20th arrondissement of Paris.

What initial decisions guided your work on the film?

The idea of filming both classes and practical sessions, of following a few students in internships and then of recording the account of their internships was present from the beginning of the project. With between their aspirations and this confrontation with reality, express their feelings, evoke what the encounter with illness produces in them, with specific patients, pathologies, types of care or technical gestures. These moments are all the more precious today because the world of healthcare, increasingly subservient to management, to “efficiency”, no longer seems to bother much about the feelings of carers, even though we know that the quality of healthcare depends to a large extent on the way they can develop it, on the possibility of expressing it in words, of putting their emotional experience at a distance.

The film does not directly denounce these economic aspects, nor the suffering of hospital staff, nor the catastrophic situation caused by under-funding and cutbacks in retirement homes… So what was your intention?

My project was not to make a film denouncing the situation, much less a pamphlet or a political piece. My intention? I feel fully in phase with André S. Labarthe, who said: “The enemy is intention” before adding, “Direction is what makes it possible to erase any trace of intention.” Besides, films always say something else – and other things – than what we wanted to say, make them say, or thought they had said. They have to retain some secrecy and leave questions unanswered. The difficulties in our health care system and the pressures on caregivers, without being at the forefront, nonetheless form the background of the film. The instructors and students refer to them more than once, and it seems to me that the political dimension of the film is no less real. Giving future carers, who are destined to remain in the shadows, a voice, showing their determination, their dignity, but also their fears, doubts and fragility, is in itself a political process. The efforts and sacrifices that many of them have to make in order to pursue their studies – while working at the same time – are perceptible in the film. Moreover, the interviews they have with their “referents” allow us an insight into many aspects of the caregiver-patient relationship, a relationship that is by definition asymmetrical, in which the dimension of power, far from being anecdotal, must be worked on in order to be contained.

Weren’t you tempted to reduce the number of protagonists and focus the film on three or four students?

That was discussed at the beginning, but we soon ruled out the idea. I couldn’t see myself making a selection among the students, especially when most of the practical work is done in groups. Very quickly, on the contrary, I wanted to take advantage of the collective aspect. The social mix of the students was an asset for the film. It would allow me to paint a very contemporary portrait of our healthcare personnel and of France today. Among the students there are some that we recognize, we see them at the school, we find them in internships or in their interviews, but this is not systematic. The film is not based on that. I could also have chosen to film only students from the same class, the “first year” for example. It is true that they are the ones we see most in the first part, but in the internships and in the interviews we also see second and third-year students. Their internships are increasingly technical, with greater responsibilities. The film does not try to say explicitly where each student is in her journey, but in some interviews, we occasionally learn this from a turn of phrase.

When did the idea of constructing the film in three parts arise? Was it planned from the beginning?

Initially, I imagined that the film would switch back and forth between classes, internships and internship reports, but as soon as I started editing I realized that would unnecessarily complicate the story, and the idea of a construction in three parts, in three “movements”, imposed itself. I like to use this word, usually reserved for music, because I think it clearly expresses how each part unfolds in a key and with a melody distinct from the other two. Moreover, this very simple narrative principle would allow me to create a kind of crescendo, with the film gradually gaining in intensity and emotion.

Do you think your presence altered the behaviour of the people you film? What impact did it have during the classes and practical sessions?

You have to try to be as discreet as possible, as unsettling as possible, but no matter how you do it, the presence of a camera, a boom or a crew, however small, always has an impact on reality. Personally, I film openly, with my presence clear to the person filmed. Sometimes, when people pretend not to see you, that’s a little too obvious. So I tell them, “Pretend I’m here!” Therefore, in my films, people can glance at the camera. As long as such looks aren’t too obvious, I don’t mind. Why should we make the audience think we weren’t there? A few days ago, in the exhibition devoted to him at the Cinémathèque française, I came across these words by Chris Marker which delighted me: “Was there ever anything more stupid than telling people, as they teach in film schools, not to look at the camera?” Of course, not everyone approaches the camera in the same way. At the Institute, out of all three years, a few dozen students did not want to be filmed. In certain situations, I therefore had to define a blind spot, indicate an area off-camera that they could occupy without being disturbed in their training.

Was it difficult persuading the patients to be filmed?

Almost everyone I approached accepted spontaneously. As soon as I explained what we were doing, they would say, “Go ahead! This is important! We need the nurses!” and so on. I never had to insist. Fortunately, because I hate that.

In the second part, among the internships, there is a sequence that contrasts with all the others. We are outdoors, there are no white coats, no medical equipment…

During their studies, nursing students are required to complete internships in different types of facilities: health centres, hospitals, schools, psychiatric hospitals, retirement homes, home care, etc. They thus learn not only to provide technical care but also other forms of accompaniment. Here, we are in a shared garden, in the heart of Paris, where patients and psychiatric nurses come to work every week. For me, it is an important scene, not only because it presents another facet of the nurse’s role, but because it is a good example of how personal relationships as such are an essential element of care.

As viewers, we can identify at times with the student nurses and at others with the patients…

That’s right. In our imagination, we go back and forth between the two, asking ourselves if we would feel capable of giving a shot, of cleaning a wound, and then, the next moment, thinking that in the event of a problem, we would like to be in the hands of a nurse who is sure of herself and experienced. Some of the footage at the hospital refers us back to our personal history, or to our loved ones. In our entourage, we all have relatives, friends who are sick, or who have been sick, and we know that we ourselves may one day be sick too. This is how the film goes beyond its subject. As is often the case with me, the “subject” is, if not a pretext, at least a doorway. Beyond the apprenticeship of the nursing profession, the film speaks to us about our fragility, human fragility.

The third part of the film gathers very moving testimonies. How easy was it for students to tell their stories in front of the camera?

Those whose internships had gone well were quite happy to do it, but for those who had experienced difficulties, it was a little more complicated. Would they agree to talk about situations in which they were not necessarily to their advantage? A few refused, but most played along, so I ended up collecting about 60 interviews. I kept thirteen. So that they would not feel trapped, I undertook to leave the room before the interview was over, giving them a space to speak without witnesses. If they wanted to talk about something very personal, about dysfunction, abuse, injustice, hostility in a healthcare setting… they could do so after we left. Their words should not penalize them or turn against them. So that they would know that they were protected, I said that the location of their internship would not be revealed and invited them to observe the same rule. Of course, I also had to preserve the anonymity of the individuals and institutions involved.

How did you avoid all compassion and voyeurism?

You’ll notice that I was not the one conducting these interviews, but the institute’s instructors, ensuring the quality of the exchanges. For my part, when I felt that our presence might be detrimental to a student, I offered to stop filming. We did it once or twice. Editing took care of the rest. Filming someone also means imprisoning them, locking them in an image. You have to be careful what you leave behind. The film is one thing, but there’s the period that comes after it too.

How did this film change your perception of the nursing world?

There’s a lot to say. Each time you approach a reality, you discover its richness and complexity, your perceptions are shaken, the clichés vanish…

You operate the camera on your films yourself, you edit them…

I started operating the camera twenty-five years ago, during the shooting of Un animal, des animaux (Animals): the cameraman I was working with could not continue. Until then I had always worked with one. At first, I hesitated about replacing him, but finally decided to take the risk, with the complicity of an outstanding assistant. Then the shooting of La Moindre des choses (Every Little Thing) came along and I chose to film it myself from A to Z. I was uneasy in the psychiatric clinic of La Borde and felt that the camera could both protect me and allow me to go towards people. Since then, I have never looked back: I have continued to shoot my films myself. When I first took up the camera, the idea was not to do the job better than a professional, with more “beautiful” or neater shots, but to have control over framing, so as not to give in to the temptation of showing everything; I felt that it was in this tension, this resistance, that things would be played out. Today, in the digital age, in the age of small cameras, of “total visibility” into which we are inexorably sinking and of the threats that weigh more and more on the private sphere, this question seems more important than ever: the frame, the border between what is in and off camera, is not only a matter of aesthetics, it is an ethical and political issue…

And editing?

I worked with an editor for a long time, but now I edit alone. I enjoy it very much. I need this lonely journey, this time facing myself. But I do have some accomplices. Every now and then I show them where I am. And for all the technical aspects, I have an assistant. As soon as I have a problem, I call him and he explains how to solve it.

Have the students and instructors seen the film? And, if so, how did they react?

As soon as the film was finished, we organized a screening for all of them at the Méliès in Montreuil. I was a little nervous. How would they react? What about the ones I cut in editing? During shooting, I had more than once had the opportunity to evoke these questions in front of them, to prepare them, to explain that montage obeys all kinds of considerations, that the director can end up discarding fantastic sequences… but there is a difference between theory and experience. Besides, when you have had the opportunity to participate in the adventure of a film and you see it for the first time, you experience that screening in a particular way, it’s normal: you wonder if you’re still in the film, you look out for the moments when you’re going to appear, etc. However, at the end of the screening, I was surprised to see that their reactions went far beyond their own presence. They were very sensitive to the general movement of the film, they found themselves in the words of others, recognized themselves in this collective portrait. For the students, as for the instructors, I have the impression that it has become “their” film.

Apart from the final credits, why is there no music in the film?

I saw no need to add any. The soundtrack is deliberately uncluttered. It is composed almost exclusively of direct sound, the grain of the voices. Not the slightest effect, no artifice. Formally it is a very simple film, without frills. I wanted us to keep as close to the words as possible.

Press kit

How did this project come about?

I had been circling this idea for a while, when Providence sent me to do scouting: in January 2016, an embolism put me straight in the emergency room and then in an intensive care unit. That was the trigger. When I was back on my feet, I decided to make this film, as a tribute to healthcare staff, especially nurses.

Why did you choose to focus on the learning stage?

Learning situations allow a director to film the foundations, highlighting what time and experience end up making imperceptible. When you see a nurse performing ordinary treatment, an injection or a blood test, say, it seems quite simple, it’s easy. Unless you’re in that line of work, you cannot imagine all the mistakes that she has learned to avoid, the rules of hygiene, the protocols, the thousand and one little things that dexterity has gradually erased. Filming classes and practical work sessions can be repetitive, funny, mysterious, comical or exciting, things sometimes hang by a thread, but from a dramaturgical point of view, it’s very fruitful. Seeing students grope, make mistakes and start again, following them in their efforts makes them appear closer and more human: will they succeed? How should they have gone about it? And would I be able to do the same? In short, we side with them, we can identify with them. And filming them learning also means filming desire. The desire to learn, to improve. The desire to graduate, to fit into society, to make oneself useful. The nursing profession is difficult, exhausting, poorly paid, often discredited within the hospital hierarchy, and yet it remains attractive and benefits from an excellent image in the mind of the general public. Indeed, this somewhat idealized image is often at the origin of the decision to become a nurse.

What made you choose the Institut de la Croix-Saint-Simon?

I wanted to shoot in Paris or in the inner suburbs, preferably not too far from home, so as not to lose too much time on the commute. I visited six or seven training institutes out of the sixty or so in the Île-de-France Region. The Croix-Saint-Simon team in Montreuil quickly became involved. The great cultural and social diversity of the students also played a role. In these days of retreat into nationalist ideas of identity, I liked the idea of filming young people ready to embark on a career focused on others. And, finally, the Montreuil Institute is a «human-sized» school: there are «only» 90 students per class. As the course lasts three years, that still makes 270 students in the whole sector and, within the framework of a shoot, that is quite a lot, but some institutes welcome three times as many. La Pitié-Salpêtrière in central Paris has nearly 1,000 students! Things turned out this way, but I must point out that the Institut de la Croix Saint-Simon is a private institution «recognized as a public utility». Private does not mean that the students come from a wealthy background. Like the population of the area in which it is located, most of them are from a modest background, and the Île-de-France Region, as well as various vocational training organizations, covers their tuition fees. Moreover, it is a secular establishment. Its name is explained by the fact that at the time of its creation, the foundation on which it depends was located rue de la Croix Saint-Simon, in the 20th arrondissement of Paris.

What initial decisions guided your work on the film?

The idea of filming both classes and practical sessions, of following a few students in internships and then of recording the account of their internships was present from the beginning of the project. With between their aspirations and this confrontation with reality, express their feelings, evoke what the encounter with illness produces in them, with specific patients, pathologies, types of care or technical gestures. These moments are all the more precious today because the world of healthcare, increasingly subservient to management, to “efficiency”, no longer seems to bother much about the feelings of carers, even though we know that the quality of healthcare depends to a large extent on the way they can develop it, on the possibility of expressing it in words, of putting their emotional experience at a distance.

The film does not directly denounce these economic aspects, nor the suffering of hospital staff, nor the catastrophic situation caused by under-funding and cutbacks in retirement homes… So what was your intention?

My project was not to make a film denouncing the situation, much less a pamphlet or a political piece. My intention? I feel fully in phase with André S. Labarthe, who said: “The enemy is intention” before adding, “Direction is what makes it possible to erase any trace of intention.” Besides, films always say something else – and other things – than what we wanted to say, make them say, or thought they had said. They have to retain some secrecy and leave questions unanswered. The difficulties in our health care system and the pressures on caregivers, without being at the forefront, nonetheless form the background of the film. The instructors and students refer to them more than once, and it seems to me that the political dimension of the film is no less real. Giving future carers, who are destined to remain in the shadows, a voice, showing their determination, their dignity, but also their fears, doubts and fragility, is in itself a political process. The efforts and sacrifices that many of them have to make in order to pursue their studies – while working at the same time – are perceptible in the film. Moreover, the interviews they have with their “referents” allow us an insight into many aspects of the caregiver-patient relationship, a relationship that is by definition asymmetrical, in which the dimension of power, far from being anecdotal, must be worked on in order to be contained.

Weren’t you tempted to reduce the number of protagonists and focus the film on three or four students?

That was discussed at the beginning, but we soon ruled out the idea. I couldn’t see myself making a selection among the students, especially when most of the practical work is done in groups. Very quickly, on the contrary, I wanted to take advantage of the collective aspect. The social mix of the students was an asset for the film. It would allow me to paint a very contemporary portrait of our healthcare personnel and of France today. Among the students there are some that we recognize, we see them at the school, we find them in internships or in their interviews, but this is not systematic. The film is not based on that. I could also have chosen to film only students from the same class, the “first year” for example. It is true that they are the ones we see most in the first part, but in the internships and in the interviews we also see second and third-year students. Their internships are increasingly technical, with greater responsibilities. The film does not try to say explicitly where each student is in her journey, but in some interviews, we occasionally learn this from a turn of phrase.

When did the idea of constructing the film in three parts arise? Was it planned from the beginning?

Initially, I imagined that the film would switch back and forth between classes, internships and internship reports, but as soon as I started editing I realized that would unnecessarily complicate the story, and the idea of a construction in three parts, in three “movements”, imposed itself. I like to use this word, usually reserved for music, because I think it clearly expresses how each part unfolds in a key and with a melody distinct from the other two. Moreover, this very simple narrative principle would allow me to create a kind of crescendo, with the film gradually gaining in intensity and emotion.

Do you think your presence altered the behaviour of the people you film? What impact did it have during the classes and practical sessions?

You have to try to be as discreet as possible, as unsettling as possible, but no matter how you do it, the presence of a camera, a boom or a crew, however small, always has an impact on reality. Personally, I film openly, with my presence clear to the person filmed. Sometimes, when people pretend not to see you, that’s a little too obvious. So I tell them, “Pretend I’m here!” Therefore, in my films, people can glance at the camera. As long as such looks aren’t too obvious, I don’t mind. Why should we make the audience think we weren’t there? A few days ago, in the exhibition devoted to him at the Cinémathèque française, I came across these words by Chris Marker which delighted me: “Was there ever anything more stupid than telling people, as they teach in film schools, not to look at the camera?” Of course, not everyone approaches the camera in the same way. At the Institute, out of all three years, a few dozen students did not want to be filmed. In certain situations, I therefore had to define a blind spot, indicate an area off-camera that they could occupy without being disturbed in their training.

Was it difficult persuading the patients to be filmed?

Almost everyone I approached accepted spontaneously. As soon as I explained what we were doing, they would say, “Go ahead! This is important! We need the nurses!” and so on. I never had to insist. Fortunately, because I hate that.

In the second part, among the internships, there is a sequence that contrasts with all the others. We are outdoors, there are no white coats, no medical equipment…

During their studies, nursing students are required to complete internships in different types of facilities: health centres, hospitals, schools, psychiatric hospitals, retirement homes, home care, etc. They thus learn not only to provide technical care but also other forms of accompaniment. Here, we are in a shared garden, in the heart of Paris, where patients and psychiatric nurses come to work every week. For me, it is an important scene, not only because it presents another facet of the nurse’s role, but because it is a good example of how personal relationships as such are an essential element of care.

As viewers, we can identify at times with the student nurses and at others with the patients…

That’s right. In our imagination, we go back and forth between the two, asking ourselves if we would feel capable of giving a shot, of cleaning a wound, and then, the next moment, thinking that in the event of a problem, we would like to be in the hands of a nurse who is sure of herself and experienced. Some of the footage at the hospital refers us back to our personal history, or to our loved ones. In our entourage, we all have relatives, friends who are sick, or who have been sick, and we know that we ourselves may one day be sick too. This is how the film goes beyond its subject. As is often the case with me, the “subject” is, if not a pretext, at least a doorway. Beyond the apprenticeship of the nursing profession, the film speaks to us about our fragility, human fragility.

The third part of the film gathers very moving testimonies. How easy was it for students to tell their stories in front of the camera?

Those whose internships had gone well were quite happy to do it, but for those who had experienced difficulties, it was a little more complicated. Would they agree to talk about situations in which they were not necessarily to their advantage? A few refused, but most played along, so I ended up collecting about 60 interviews. I kept thirteen. So that they would not feel trapped, I undertook to leave the room before the interview was over, giving them a space to speak without witnesses. If they wanted to talk about something very personal, about dysfunction, abuse, injustice, hostility in a healthcare setting… they could do so after we left. Their words should not penalize them or turn against them. So that they would know that they were protected, I said that the location of their internship would not be revealed and invited them to observe the same rule. Of course, I also had to preserve the anonymity of the individuals and institutions involved.

How did you avoid all compassion and voyeurism?

You’ll notice that I was not the one conducting these interviews, but the institute’s instructors, ensuring the quality of the exchanges. For my part, when I felt that our presence might be detrimental to a student, I offered to stop filming. We did it once or twice. Editing took care of the rest. Filming someone also means imprisoning them, locking them in an image. You have to be careful what you leave behind. The film is one thing, but there’s the period that comes after it too.

How did this film change your perception of the nursing world?

There’s a lot to say. Each time you approach a reality, you discover its richness and complexity, your perceptions are shaken, the clichés vanish…

You operate the camera on your films yourself, you edit them…

I started operating the camera twenty-five years ago, during the shooting of Un animal, des animaux (Animals): the cameraman I was working with could not continue. Until then I had always worked with one. At first, I hesitated about replacing him, but finally decided to take the risk, with the complicity of an outstanding assistant. Then the shooting of La Moindre des choses (Every Little Thing) came along and I chose to film it myself from A to Z. I was uneasy in the psychiatric clinic of La Borde and felt that the camera could both protect me and allow me to go towards people. Since then, I have never looked back: I have continued to shoot my films myself. When I first took up the camera, the idea was not to do the job better than a professional, with more “beautiful” or neater shots, but to have control over framing, so as not to give in to the temptation of showing everything; I felt that it was in this tension, this resistance, that things would be played out. Today, in the digital age, in the age of small cameras, of “total visibility” into which we are inexorably sinking and of the threats that weigh more and more on the private sphere, this question seems more important than ever: the frame, the border between what is in and off camera, is not only a matter of aesthetics, it is an ethical and political issue…

And editing?

I worked with an editor for a long time, but now I edit alone. I enjoy it very much. I need this lonely journey, this time facing myself. But I do have some accomplices. Every now and then I show them where I am. And for all the technical aspects, I have an assistant. As soon as I have a problem, I call him and he explains how to solve it.

Have the students and instructors seen the film? And, if so, how did they react?

As soon as the film was finished, we organized a screening for all of them at the Méliès in Montreuil. I was a little nervous. How would they react? What about the ones I cut in editing? During shooting, I had more than once had the opportunity to evoke these questions in front of them, to prepare them, to explain that montage obeys all kinds of considerations, that the director can end up discarding fantastic sequences… but there is a difference between theory and experience. Besides, when you have had the opportunity to participate in the adventure of a film and you see it for the first time, you experience that screening in a particular way, it’s normal: you wonder if you’re still in the film, you look out for the moments when you’re going to appear, etc. However, at the end of the screening, I was surprised to see that their reactions went far beyond their own presence. They were very sensitive to the general movement of the film, they found themselves in the words of others, recognized themselves in this collective portrait. For the students, as for the instructors, I have the impression that it has become “their” film.

Apart from the final credits, why is there no music in the film?

I saw no need to add any. The soundtrack is deliberately uncluttered. It is composed almost exclusively of direct sound, the grain of the voices. Not the slightest effect, no artifice. Formally it is a very simple film, without frills. I wanted us to keep as close to the words as possible.

Les Inrockuptibles - Festival de Locarno, 4 de augusto de 2018

Dans De chaque instant, Nicolas Philibert se concentre sur une école d’infirmier-ière.s. À travers ce dernier documentaire, le cinéaste portraiture à nouveau l’état de la France contemporaine.

À chaque nouveau film de Nicolas Philibert, on a l’impression de retrouver un vieil et cher ami. Un ami cinéaste en l’occurrence, qui vous prend par la main pour vous faire découvrir un petit pan du monde, de la société, grâce à une qualité de regard, d’écoute et d’attention à l’autre jamais pris en défaut.

Après avoir exploré un grand musée national (La Ville Louvre), une école en milieu rural (Être et avoir), ou une grande antenne publique (La maison de la radio), notre cinéaste observateur et analyste de la France a cette fois posé regard et caméra dans une école d’infirmier-ière.s. On peut voir une certaine logique à ce choix tant la façon de pratiquer le cinéma de Philibert a quelque chose des métiers du soin.

Couvrir les spécificités du métier

De Chaque instant se déploie en trois chapitres, qui correspondent aux trois années d’apprentissage de ce métier essentiel et sous-estimé. D’abord, l’apprentissage théorique des bases : se laver systématiquement les mains, manipuler un patient, savoir ne pas reculer face au sang, à la saleté, aux apparences physiques entamées, apprendre à dissimuler ses affects… Ensuite, passer à la pratique pendant les stages, gérer des vrais patients, savoir faire une injection ou une prise de sang avec rapidité et précision. Enfin, le debriefing des stages et le choix de l’orientation (car comme les médecins, les infirmier-ière.s peuvent suivre différentes spécialisations).

L’air de rien, tel une souris silencieuse se contentant d’observer modestement les choses, Philibert compose une maïeutique qui couvre tous les aspects de ce métier : le rapport aux corps étrangers, la proximité quotidienne avec la maladie, la douleur voire la mort, les diverses motivations des élèves (se sentir utile, aider les autres, répondre à un trauma personnel), le surmenage aussi des personnels de santé chroniquement en sous-effectifs, libéralisme oblige…

Un miroir de la France contemporaine

Comme toujours, en explorant un microcosme spécifique sans surplomb ni commentaire (un peu à la façon de Frederick Wiseman), Nicolas Philibert parvient à montrer beaucoup plus que son sujet apparent, la situation des apprenti.e.s infirmier-ière.s devenant à travers son regard une vue en coupe de l’état politique, social et psychologique du pays.

D’aucuns pourraient reprocher au cinéaste de se répéter un peu, de ne jamais changer de méthode. Sauf que Philibert change de sujet d’observation à chaque film et que c’est en vertu de cela qu’on lui donne raison de s’arrimer à la permanence des grands principes fondant sa mise en scène et garants de la cohérence de son œuvre : ainsi, quand on ajoute De Chaque instant à La Moindre des choses, Être et avoir, La Maison de la radio et les autres, on réalise que chaque film de Nicolas Philibert est certes un monde en soi mais aussi une pièce d’un ensemble plus vaste montrant la France des trente dernières années avec autant de pertinence, de finesse et de profondeur que les meilleurs romans, essais et films de fiction. Difficile de demander mieux ou plus à un cinéaste.

Télérama - 29 août 2018

Le réalisateur d’Etre et avoir suit des élèves infirmiers, entre soins des corps et écoutes des maux. Et sous son œil, ce cheminement touche à la grâce.

Le dernier film de Nicolas Philibert était La Maison de la Radio (2013), documentaire qui donnait corps aux voix de Radio France. Cinq ans plus tard, c’est la formation d’élèves infirmiers, souvent très jeunes, très motivés et d’une belle candeur, qu’il nous invite à suivre. Dès la première scène, on voit des mains se frictionner sous un filet d’eau froide pour éliminer savon et impuretés. Elles s’exerceront bientôt à prendre la tension sur un bras, effectuer une intra- musculaire sur un tronc en plastique, apprendre à lever de son lit une étu- diante feignant l’hémiplégie ou à placer sur un brancard une fausse accidentée. Organisé en trois parties, le film nous montre les élèves de l’institut de Montreuil (93) en classe, puis en stage, et les écoute témoigner de leur rencontre parfois rude avec le monde hospitalier. Une étudiante de première année fond en larmes en évoquant la pression et les humiliations qu’elle a subies dans un service hostile. Un autre raconte, en re- vanche, comment il s’est senti utile en accompagnant, par son écoute, un homme dont il ne savait rien dans ses derniers moments. Car si le film s’ouvre sur des corps, ce sont bien les mots qui relient les êtres — soignants et patients, formateurs et élèves — lors de ces entretiens post-stages qui haussent le film, dans les quarante dernières minutes, jusqu’à une forme d’universalité.

Nicolas Philibert y fait preuve de cette justesse de regard, mélange d’ex- trême attention et de tact, qui caractérise son art, exempt de lyrisme, mais pas d’humour ni d’émotion. C’est le cas dans cette scène singulière, l’une des plus simples et des plus belles, la seule tournée en extérieur, qui suit la conversation d’un stagiaire avec une femme qu’on imagine atteinte de troubles psychiatriques. Il est assis à côté d’elle, s’inquiète de savoir si elle a froid, ramasse sur le sol le tabac qu’elle a laissé s’échapper de ses mains, l’écoute fredonner une chanson de Françoise Hardy qu’il ne connaît pas. L’ascendant naturel du soignant sur le patient s’efface au profit d’un simple échange, attentif et doux, entre deux êtres fragiles, au cours du- quel le jeune homme n’hésite pas à confier à cette femme qu’elle a beaucoup à lui apprendre. On pense, alors, que Nicolas Philibert pourrait adresser les mêmes mots à toutes les personnes qu’il filme. Et l’on songe à La Moindre des choses, qu’il a tourné, voilà plus de vingt ans, à la clinique psychiatrique de La Borde (41), autre merveilleux film de ce radiographe subtil et délicat de notre humanité.

Télérama - 29 août 2018

Se confronter au corps de l’autre, ses douleurs, ses défaillances… En filmant l’apprentissage des soins infirmiers, Nicolas Philibert sonde avec tact les relations soignants-soignés.

Six mois durant, le documentariste Nicolas Philibert a filmé les étudiants de l’Institut de formation en soins infirmiers (Ifsi) de la Croix-Saint-Simon, à Montreuil (93). De chaque instant, sorti au cinéma le 29 août, s’attache avec finesse et émotion à ces nombreuses femmes et quelques hommes qui ont choisi de consacrer leur vie à s’occuper d’autrui. A travers leur apprentissage et leurs premières interventions en milieu hospitalier, le film soulève de nombreuses questions sur les tensions d’un secteur particulièrement soumis à la pression du rendement, mais aussi sur le rapport à l’autre, la transmission et les relations entre générations.

Qu’est-ce qui vous a inspiré l’idée d’un documentaire sur l’apprentissage du métier d’infirmier ?

Je suis parti de l’idée du corps. Parce que le cinéma (documentaire ou de fiction), c’est toujours des corps filmés, des présences corporelles. J’ai longuement tourné autour de ce mot sans savoir par quel bout le prendre. Cela arrive souvent : on a en tête une idée qu’on n’arrive pas à définir, et c’est par la rencontre inattendue avec une situation qu’une solution, tout à coup, se présente. En l’occurrence, mon hospitalisation. Une embolie pulmo- naire m’a envoyé par deux fois aux urgences, puis dans un service de soins intensifs. Pendant le montage de La Maison de la radio et cinq ans plus tard, en janvier 2016, j’ai été à deux doigts d’aller voir de l’autre côté à quoi ça ressemble. Je tournais autour de l’idée du corps, et mon propre corps m’a envoyé en repérages à l’hôpital. Sans doute ai-je été un patient difficile, car je souffrais énormément. Chaque respiration me faisait l’effet d’un coup de poignard, le moindre geste m’arrachait des cris, et incliner mon lit prenait une dizaine de minutes. Mais, petit à petit, la morphine m’a permis d’aller mieux et j’ai pu engager des bribes de conversation avec les infir- mières et les aides-soignantes. Voilà comment le déclic a eu lieu. Peu après ma seconde hospitalisation, j’ai décidé de faire ce film.

Le corps apparaît d’ailleurs dans tous ses états…

Le film se penche en effet sur toutes sortes de corps : d’abord des bouts de mousse utilisés par les étudiants pour apprendre à piquer, puis des manne- quins servant à pratiquer les tech- niques de réanimation, puis des corps complices (une étudiante simulant une pathologie, un étudiant faisant la femme enceinte…), enfin de vrais pa- tients lors des stages à l’hôpital. Mais les corps, ce sont aussi les gestes que ces futurs infirmiers et infirmières apprennent à maîtriser. Quand on est hospitalisé ou que l’on rend visite à un patient, tous ces gestes exécutés avec dextérité par des personnes expéri- mentées ne semblent pas si difficiles. Filmer leur apprentissage par des étu- diants qui tâtonnent permet de les dé- cortiquer et de révéler la complexité de leur enchaînement.

Qu’est-ce qui pousse les étudiants de l’Ifsi à se lancer dans un métier si difficile ?

Certains sortent du bac ou d’un an de prépa ; d’autres ont suivi un parcours d’aide-soignant avant de reprendre leurs études. Pour beaucoup, cette formation est un véritable ascenseur social. Le désir d’être utile participe aussi à leur motivation, mais mieux vaut s’abstenir de parler de vocation : le milieu rejette à juste titre ce terme, qui permet de justifier leurs bas salaires en renvoyant à l’époque où les infirmières étaient des bénévoles catholiques. Depuis les années 1960, la profession a beaucoup évolué. Elle s’est organisée, structurée. Il y a au- jourd’hui un savoir infirmier spéci- fique, distinct du savoir médical. Une recherche en soins infirmiers est même en train de se constituer. De plus en plus d’actes techniques qui revenaient aux médecins sont et se- ront confiés aux infirmiers. Beaucoup se plaignent de la manière dont le relationnel est déjà mis à mal, faute de temps à lui consacrer. Cela me fait penser à cette formule du psychiatre Lucien Bonnafé que citait Jean Oury [fon- dateur de la clinique psychiatrique de La Borde, où Nicolas Philibert a tourné La Moindre des choses, ndlr] : « Le potentiel soignant du peuple. » Un professeur bardé de diplômes n’est pas forcément plus soignant que la femme de ménage venue passer la serpillière dans la chambre, et qui pose son balai pour papoter dix minutes avec un patient.

Dans le film, la formation soustrait rapidement les étudiants aux enseignements techniques, pour les exposer à des réalités humaines auxquelles ils ne sont pas forcément préparés.

Dès la première année, le réel les rattrape en effet d’une manière souvent brutale. Ils sont nombreux à faire leur premier stage dans des Ehpad, après deux mois de cours et de travaux pratiques. Ils se trouvent alors confrontés à des corps vieillissants, sur lesquels ils apprennent à faire des toilettes intimes. Ils ont aussi affaire à des personnes qui n’ont plus toute leur tête. Et à la mort, inévitablement. Ce stage de première année est pour chacun un baptême du feu. Certains décrochent à ce moment-là ; d’autres renoncent en troisième année, quand se profile la prise de responsabilités. Filmer des étudiants, souvent jeunes, confrontés à la fin de vie est l’une des raisons qui m’ont donné envie de faire ce film. Il leur faut du cran, apprendre à mettre de la distance sans se faire une carapace. Se protéger, sans pour autant devenir insensible ou se réfugier dans la technique.

Cette question ne se pose-t-elle pas pareillement dans la pratique documentaire ?

Il y a quelque chose de voisin entre filmer et soigner. Les outils ne sont pas les mêmes, mais il s’agit toujours de faire preuve d’attention. Il m’est arrivé d’en parler aux étudiants que je filmais. Je leur disais : « Ce que vous apprenez requiert une écoute. Je fais un peu la même chose ; j’essaie de m’ap-procher, de comprendre, de filmer en essayant de ne pas faire trop mal. »

Et de ne pas verser dans un excès d’empathie…

Sur l’émotion au cinéma, le cinéaste Marcel Hanoun a écrit : « La capacité de l’image à émouvoir ne devrait pas abuser de celle du spectateur à être ému. » Ça me semble très juste. C’est pourquoi, dans certaines situations, il m’arrive de poser ma caméra. Je l’ai fait lors des entretiens que les formateurs mènent avec les étudiants à leur retour de stage. Deux ou trois fois, je me suis dit : « J’arrête, ça ne me regarde pas. »

Ces retours de stage font de la troisième partie du film la plus riche et la plus émouvante.

La première partie, consacrée aux cours et aux travaux pratiques, c’est un peu la fiction, l’apprentissage des règles de bonne conduite. La deuxième, qui suit les étudiants en stage à l’hôpital, c’est la confrontation avec le réel. Ils sont alors souvent livrés à eux- mêmes, mis à l’épreuve et parfois mis à mal par les équipes, qui attendent d’eux qu’ils sachent des choses qu’on ne leur a pas apprises. La troisième partie permet d’entendre ce que la deuxième pouvait difficilement montrer. Comme les maltraitances dont ils sont parfois victimes au sein des services dans lesquels ils effectuent leur stage, évoquées par certains.

Le film accède alors à une dimension politique.

Aucun de mes films ne repose sur un discours qu’il s’agirait d’imposer. Pourtant ils ont tous à voir avec le politique, ne serait-ce qu’à travers la façon dont ils posent des questions et les maintiennent ouvertes. Traiter le spectateur comme un sujet autonome et responsable est un choix politique, de même que donner la parole à des gens qui ne l’ont que trop rarement au cinéma. Si mes films n’assènent rien, on entend dans De chaque instant le manque criant de personnel, le poids grandissant des tâches administratives, la tension dans les équipes… Pendant que je tournais, un livre est paru, qui énonce des cas de harcèlement et de maltraitance à l’encontre d’étudiants en médecine et en soins infirmiers (1). Le bout-à-bout des témoignages, tous plus épouvantables les uns que les autres, est accablant, mais le tableau qu’il dresse a quelque chose d’univoque. Je ne me sentirais pas de faire un documentaire de cette trempe-là. J’aime amener de la complexité dans mes films, entrouvrir des fenêtres, suggérer… La relation soignant-soigné, par exemple, qui est longuement évoquée dans les retours de stage, est une relation asymétrique, une relation de pouvoir que les étudiants doivent apprendre à gérer.

Du type de celle du documentariste aux personnes qu’il filme ?

Il y a de ça. Les films, qu’ils soient documentaires ou non, portent la trace de la relation du ou de la cinéaste avec les personnes filmées. Je tourne « à découvert », dans une grande proximité. Je suis parfois à un mètre à peine, avec quelqu’un qui tient la perche et parfois quelqu’un d’autre qui fait le point. On essaie d’être dans une présence à la fois affirmée et discrète. En fin de compte, 80 % du travail consiste dans la façon d’« être avec ». Tous mes films traitent d’ailleurs de la question du rapport à l’autre et de l’altérité, c’est- à-dire ce qui nous grandit. L’identique, l’immobile, le transparent ne nous aident pas à réfléchir. Ce qui nous fait penser, c’est le mouvement, l’hétérogène. D’un film à l’autre, les mêmes questions me guident. Qu’est-ce que je fais là ? A quoi ça rime de prendre une caméra pour aller filmer des étu- diants et des patients ? Pourquoi ai-je besoin de faire ça ? Et comment les filmer ? Pour le dire autrement, ça ne m’intéresse pas de faire un film si le projet ne me met pas face à moi-même, ne me confronte pas à une question politique, éthique et esthétique. Si ces questions n’arrivent pas en avalanche, alors pour moi ça ne vaut pas la peine.

Propos recueillis par François Ekchajzer

1 Omerta à l’hôpital. Le livre noir des maltraitances faites aux étudiants en santé, de Valérie Auslender, éd. J’ai lu.

Écran total

En salles le 29 août, sélectionné en séance spéciale au Festival d’Angoulême, le nouveau film de Nicolas Philibert, produit par Archipel 35, s’impose comme l’une des œuvres majeures de 2018.

C’est l’un des longs métrages essentiels de cette rentrée cinématographique. Distribué le 29 août par Les Films du Losange, De chaque instant, le nouveau documentaire de Nicolas Philibert, réalisé avec la complicité de Linda De Zitter, s’impose en effet comme une œuvre majeure, parmi les plus marquantes de cette année 2018.

Sélectionné en séance spéciale par le Festival du film francophone d’Angoulême, après être passé début août par le Festival de Locarno, où il était présenté hors compétition, il suit des femmes et des hommes se formant à la profession d’infirmier. Nicolas Philibert les filme dans leur phase d’apprentissage théorique et pratique à l’école – le réalisateur a tourné à l’Institut de formation paramédicale et sociale (IFPS) de la fondation Œuvre de la Croix-Saint-Simon, à Montreuil –, durant leurs stages, et lors de leurs retours de stages, où ils s’entre- tiennent, avec leurs formateurs, sur les expériences qu’ils ont vécues. “Cela faisait quelque temps que j’avais envie de mettre en avant le métier d’infirmier – un métier de l’ombre, qui mobilise énormément de connaissances, demande de suivre des études denses, et où le poids des responsabilités est très important. Par ailleurs, j’aime beaucoup filmer ce qui relève de la transmission, de l’apprentissage”, indique Nicolas Philibert.

Tourné entre février et juillet 2017, De chaque instant a été produit par Archipel 35, la société de Denis Freyd. “Le long métrage a bénéficié d’un budget d’environ 1 M€, précise le producteur. Il a été coproduit par France 3 Cinéma et par le Japonais Longride. Celui-ci distribue les films de Nicolas au Japon et a décidé, comme il l’avait fait pour La Maison de la Radio, de s’engager également en tant que coproducteur.”

De chaque instant est donc distribué par Les Films du Losange, partenaire historique des films de Nicolas Philibert, et est vendu par Doc & Film International. Outre le Japon, il a d’ores et déjà été acheté par la Suisse, le Bénélux, Taïwan et la Chine. L’édition DVD sera assurée par Blaq Out, tandis que la plateforme UniversCiné détient le mandat VàD. De chaque instant a été préacheté par Ciné+ et a bénéficié du soutien de la région Ile-de-France, du CNC et du Programme Europe Créative Media.

Dans l’Hexagone, la sortie de De chaque instant se fera sur une combinaison d’environ 100 copies. Nicolas Philibert va effectuer de nombreux déplacements pour présenter le long métrage, participer à des débats, mais aussi pour assister à des projections spéciales organisées par le monde infirmier. “J’ai toujours accompagné la diffusion de mes films, car il me semble primordial de venir à la rencontre des spectateurs. Et, lors des échanges avec le public, on apprend aussi beaucoup sur son propre travail, que l’on peut percevoir autrement”, souligne Nicolas Philibert.

Enfin, en cette rentrée, Nicolas Philibert est au cœur d’une autre actualité. En effet, Les Films du Losange ressortira en salles, à partir du 5 septembre, neuf de ses films, dont Nénette, Retour en Normandie, et Être et avoir. Ils seront visibles en version restaurée. Un coffret DVD les réunissant, et dans lequel on trouvera d’autres œuvres de Nicolas Philibert, sera édité par Blaq Out. Il devrait être disponible à la fin de l’année.