This film has been directed with the complicity of Linda De Zitter

Camera Nicolas Philibert, alternately assisted by Rémi Jennequin, Pauline Pénichout, Camille Bertin, Katell Djian • Sound Erik Ménard, François Abdelnour • Intern Baptiste Vidal • Editing Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Janusz Baranek, Meryll Chandru • Sound editing & mix Nathalie Vidal, assisted by Élias Boughedir • Grading Christophe Bousquet • Post-Production Delphine Passant • Coproducer Norio Hatano • Producers Miléna Poylo & Gilles Sacuto, Céline loiseau, assisted by Clément Reffo • A coproduction TS Productions, France 3 cinéma, Longride • With the participation of Ciné +, France Télévisions, Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée, Les Films du Losange, Universciné • With the support of Région Île-de-France • In collaboration with CNC • With patients and cartegivers from the Adamant daycare center.

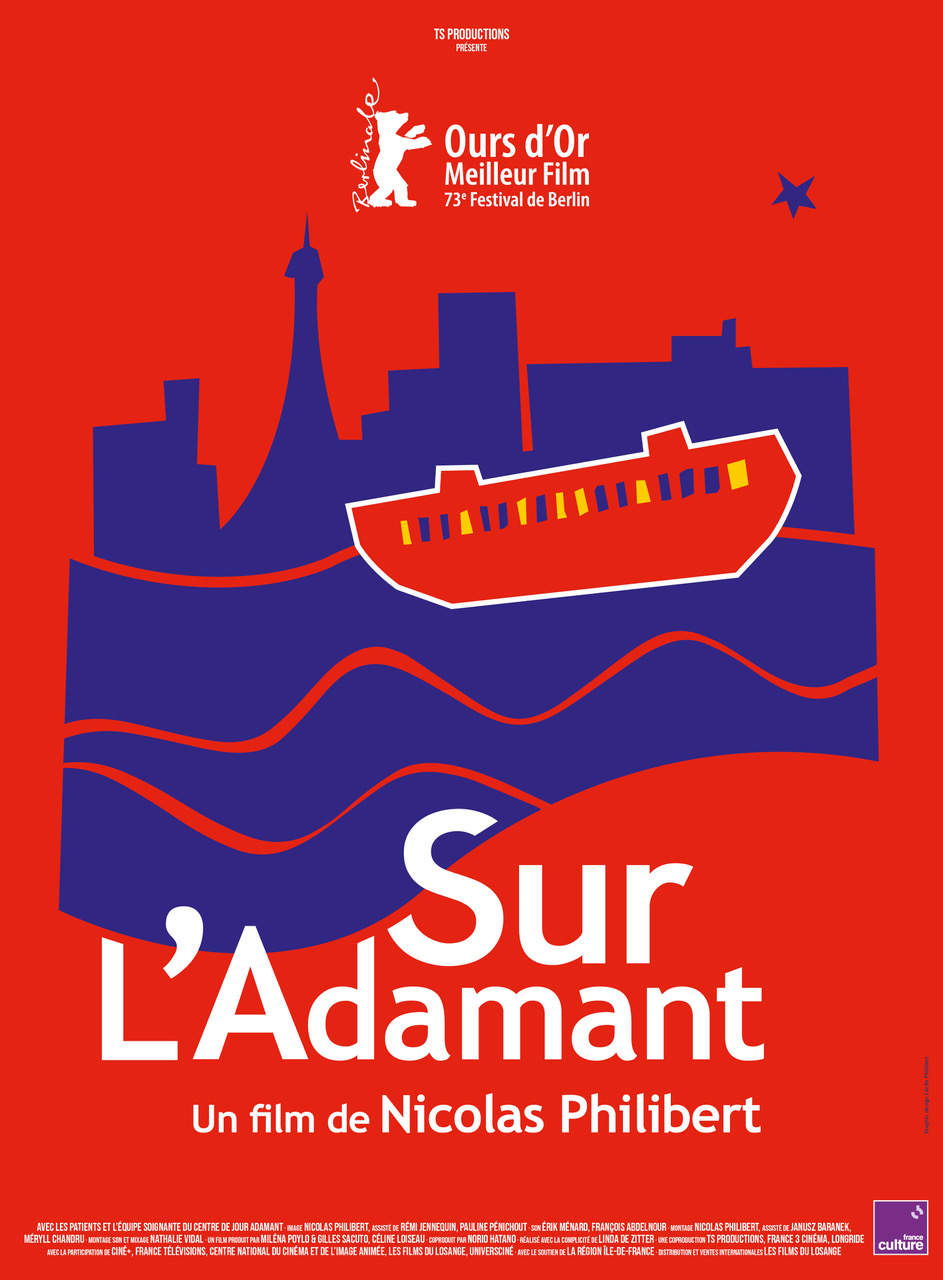

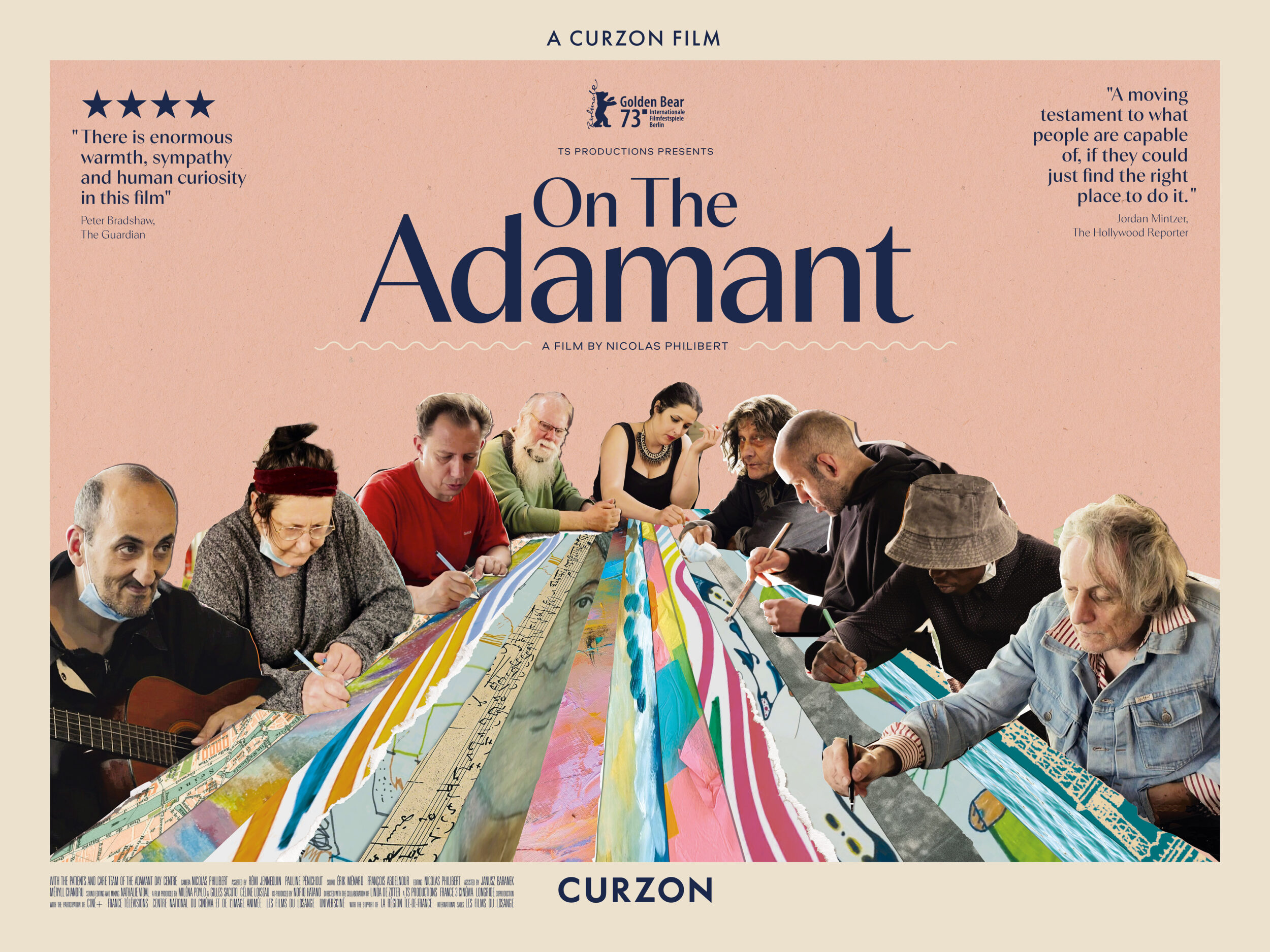

Golden Bear and Oecumenical Jury mention, 73e Berlinale – february 2023 • Best Moral Approach Award, Makedox Film Festival, North Macedonia – August 2023 • Best Documentary Award, Silk Road International Film Festival, Fuzhou, Chine – September 2023 • Premio Toni Serra (Abu Ali), CLAM / Festival internacional de cine social de Catalunya – October 2023 • Prix Utopia, Festival Castellinaria, Bellinzona (Suisse) -november 2023 • Bronze Star Award, El Gouna International Film Festival, Egypt – december 2023 • Prix « de la thématique », Festival du film méditerranéen ARTE-MARE, Bastia – Octobre 2024 • Nomination 36th European Film Awards, Cat. « Best European Documentary » • Nomination 29e Lumières Awards (international press), category « Best documentary » • Nomination César 2024, cat. « Best documentary » • Nomination Lux Award 2024.

Distribution France & Internationale Sales Les Films du Losange

French release : April 19, 2023

“La cámara te da un poder considerable sobre los demás”, por Nicolas Philibert

Quería situar la película en una región de media montaña, de clima rudo e invierno difícil y, por este motivo, empecé a buscar en la zona del Macizo Central. Antes de decidirme por esta escuela, entré en contacto con más de 300 y visité más de 100. Para mí era importante conseguir una clase de pocos niños (entre 10 y 12 alumnos), para que cada niño fuera perfectamente identificable y pudiera convertirse, por tanto, en un “personaje”. También quería que el abanico de edades fuera lo más amplio posible – del parvulario al último curso de primaria – por el ambiente que surge en esas pequeñas comunidades heterogéneas donde los niños tienen que aprender cuanto antes a ser autónomos, responsables de sí mismos y solidarios con los demás. Además, el aula tenía que ser lo bastante amplia y luminosa para no tener que añadir luz artificial.

Al principio, buscaba de manera un tanto aleatoria. Una profesora me mandaba a otra, y así, vuelta a empezar. Pero al cabo de un tiempo, para evitarme kilómetros innecesarios, decidí pasar por los servicios de educación de cada zona. Sin duda, gané en eficacia, pero aún así, tardé mucho tiempo en encontrar lo que buscaba. Había que enviar correos, esperar a que se decidieran a contestarme… Se notaba una cierta desconfianza. Es normal: diez semanas de rodaje en una clase, no es algo tan evidente.

Naturalmente, yo sabía que muchas cosas dependían de la elección del maestro, pero en este asunto, estaba bastante abierto a todas las posibilidades. Podía ser un hombre o una mujer, joven o menos joven… no tenía ninguna idea preconcebida.

Evidentemente, cada uno tenía su estilo, su personalidad, pero la mayor parte de los maestros que conocí daban la sensación de estar muy implicados en lo que hacían.

En cuanto a los métodos pedagógicos, variaban mucho de una clase a otra, pero ese aspecto era más bien secundario para mí. Lo importante era el ambiente general de la clase y no las características de tal o tal método de aprendizaje de la lectura. No quería hacer una película para especialistas.

Entonces, ¿por qué elegí esa clase? Se acercaban las vacaciones de Todos los Santos, había visitado algo más de cien escuelas, llevaba cuatro meses buscando, todo el día en la carretera, y, al entrar en esa clase, tuve la sensación de que la había encontrado. El aula era grande, luminosa, el número y la edad de los alumnos se correspondía con lo que buscaba y me dio la sensación de que con este maestro experimentado, un poco autoritario, nuestra presencia no pesaría demasiado. Parecía bastante disponible, dispuesto a darnos asilo durante 10 semanas. Al mismo tiempo, estaba rodeado de un cierto halo de misterio, algo secreto, que le convertía en un “personaje”. Por último, el hecho de elegir a un hombre, mientras que en la actualidad es una profesión ejercida en un 85% por mujeres, me parecía que podía reforzar esa dimensión misteriosa, ideal para alimentar la imaginación del espectador.

Cuando le conocí, parecía sorprendido de que se pudiera hacer un documental para el cine sobre un tema tan poco “espectacular”. Le expliqué mi manera de ver las cosas, precisando que no buscaba ni lo pintoresco, ni la nostalgia, sino el deseo de seguir, lo más cerca posible, el trabajo y el avance de los alumnos, Estaba convencido de que filmar a un niño en plena batalla con una resta podía convertirse en una auténtica epopeya…

Los padres dieron su consentimiento casi inmediatamente. Cuando me reuní con ellos la primera vez, me parecía importante precisarles que a sus hijos no siempre se les mostraría en las situaciones más gratificantes, pues de ser así, no habría película, al menos no habría historia. También les adelanté algunos datos sobre el montaje, les dije que habría que eliminar algunas tomas, sin duda tendría que sacrificar algunas escenas hermosas, ya que un montaje no es un “best-off” sino una construcción regida por leyes internas y también por los deseos del realizador, de tal modo, que a priori, sus hijos no aparecerían seguramente a partes iguales en la película… En fin, para disipar cualquier duda, quise manifestar de entrada la subjetividad de mi mirada. A partir de ahí, cada uno luego podía aceptar o no. Habría bastado que un único padre se mostrara reticente para tener que cambiar de escuela.

El rodaje duró diez semanas, repartidas en varias sesiones entre enero y junio de 2001. El primer día nos tomamos todo el tiempo necesario para explicarles a los niños cómo íbamos a trabajar, para qué servía todo el material, etc… Todos estuvieron mirando por el visor, jugando con el zoom, se pusieron los auriculares… Luego, el maestro recuperó el control de la clase, ellos se pusieron a trabajar, y nosotros también.

Éramos un equipo de cuatro personas: un jefe de fotografía, un ingeniero de sonido, un ayudante de cámara y yo. Técnicamente era muy complicado. El ingeniero de sonido tenía que cubrir solo toda la clase y obviamente nunca sabíamos con antelación quién iba a intervenir. En cuanto a la imagen, había muchas trampas, teníamos que vigilar permanentemente nuestros reflejos en las ventanas y en el encerado. Como optamos por no agregarles luz a los tubos fluorescentes existentes, teníamos poca profundidad de campo y ningún margen de error para el enfoque. Pero es lo natural en ese tipo de rodaje y esto obliga a cada uno a dar lo mejor de sí mismo.

Muchas veces me han preguntado que cómo conseguíamos que se olvidaran de nosotros, pero no se trata de eso. Evidentemente, intentábamos ser lo más discretos posibles, para no interferir en el correcto funcionamiento de la clase, pero la cuestión no era que se olvidaran de nosotros. Lo importante es conseguir que te acepten, ¡que no es lo mismo! Tratar de que se olviden de ti es como si quisieras rodar a las personas sin su consentimiento, a escondidas, como para robarles algo. Mi cámara no es una cámara de vigilancia. Al contrario, se trataba de estar ahí. A su lado. Estar presentes en lo que hacían. De hacerles entender que no estábamos ahí para forzar puertas y ventanas, para filmarles a toda costa, en cualquier circunstancia. Ni para juzgarlos. A veces, hay que saber renunciar, dejar la cámara en el suelo. En la clase, hay niños a los que filmé muy poco, sobre todo entre los mayores. La cámara les molestaba. Por ejemplo, filmé mucho a Jojo pero a Laura, su hermana, muy pocas veces; porque la cámara la intimidaba mucho. Hay que tener mucho cuidado. La cámara te da un poder considerable sobre los demás, y todo consiste en saber cómo no abusar de ese poder. No suele ser cosa fácil. En el fragor de la batalla, te puedes dejar llevar por la emoción. Si un niño está molesto, si no quiere que le filmes en tal o tal situación, quizá no se atreva a decirlo delante de sus compañeros.

Hay que encontrar la “distancia correcta”, que varía en función del contexto y de la naturaleza de las relaciones que tienes con las personas a las que filmas. Cada película es una historia única, y esta cuestión de los límites se plantea una y otra vez… Una película encierra a la gente que filmas en una imagen dada, en un momento preciso de su vida, y hay que tener en cuenta que esta imagen se les pegará a la piel, y no siempre podrán librarse de ella. Ésa es la diferencia entre el documental y la ficción…

El momento en que el profesor pregunta a Olivier sobre la salud de su padre llegó de manera totalmente inesperada. Al principio, cuando empecé a filmar su conversación, sólo iban a hablar de trabajo. El profesor trataba de pinchar un poco a Olivier: si no quería repetir, se tenía que poner las pilas. Y, de repente, cambió de tema, le preguntó por su padre, y Olivier se echó a llorar. Detrás de la cámara, yo no sabía dónde meterme. En el montaje, dudé mucho si quedarme con la escena o no. Lo mismo con la conversación entre el maestro y Natalie, que conservé, también, después de muchas dudas. Pero pensé que cuando llegara el momento, cuando descubrieran la película, tanto uno como otro serían lo bastante fuertes como para afrontar las imágenes.

Las estaciones, el tiempo que pasa… para mí era esencial. Muchas veces, después de clase, nos íbamos por los caminos, a filmar el paisaje. Quería filmar la naturaleza en su belleza pero, también, en lo que puede tener de inquietante. De hecho, si la película tiene algo de cuento, se lo debe sobre todo a estos planos: a esos árboles un poco fantasmagóricos agitados por el viento, al silencio que pesa en esos grandes espacios, a la soledad, a los campos de cebada por los que buscan a Alizé…

La película juega mucho con esta oposición entre el interior y el exterior, el calor y el frío. Por una parte, la escuela, el calor de la lumbre, el hecho de estar todos juntos, rodeados por una especie de capullo protector; por el otro, el vasto mundo, su violencia, los elementos que se desatan, la nieve, el viento, la tormenta, ese rebaño de vacas que los ganaderos tratan de reunir…

Siguiendo a los “personajes” de esta clase, he querido compartir con el espectador las pruebas a las que se enfrentan, sus momentos de felicidad, sus pequeños dramas. Es una película muy abierta. Personalmente, veo una cierta gravedad, incluso una cierta violencia, aunque sea contenida. Antes del rodaje, creo que me había olvidado de lo difícil que es aprender y, también, de lo difícil que es crecer. Esta inmersión en la escuela me lo ha recordado con toda su fuerza. Quizá sea el verdadero tema de la película.

The Adamant is moored on Quai de la Rapée, on the right bank of the Seine, a stone’s throw from the Gare de Lyon railway station. It is a “day centre” and part of the Paris Central Psychiatric Group, which also includes two CMPs (Centres Médicaux Psychologiques – Psychological Medical Centres), a mobile team, and two units within the Esquirol psychiatric hospital – famous in the past as the Charenton asylum – which in turn is attached to the Saint-Maurice hospital complex.

Therefore, this is not an isolated place because the interlinked units that make up the group form a network in which patients and carers are constantly on the move, each one able to build up his or her own cartography and so find an individual solution among the different elements on offer.

With large bay windows opening onto the Seine, the Adamant is a wooden building with a surface area of 650 m2. The architects who designed it worked closely with the carers and the sectors’ patients.

It opened in July 2010.

As public psychiatric care in France is divided into sectors, the Adamant, along with the other reception centres in the Paris Central Group, is dedicated to patients from the first four arrondissements of the capital.

Some patients visit every day, others only come from time to time, at regular or irregular intervals. They are of all ages and from a wide range of social backgrounds. The week begins with breakfast for everyone who is there, and then it’s Monday’s weekly meeting that brings together carers and patients. Everyone can add the points they want to see talked about to the agenda, news is exchanged, projects are discussed: an outing to the theatre, an upcoming guest, a walk in the forest, a concert, an exhibition…

The care team is made up of nurses, psychologists, occupational therapists, a psychiatrist, a secretarial office, two hospital service agents, and various outside contributors from a range of backgrounds. Permanent attention is paid to everyday life. Everyone, both patients and carers, is invited to help to “build it up together”.

The therapeutic function concerns the group as a whole. Everyone can get involved whatever their title, status, diplomas, place in the hierarchy, personality or style. It will not shock anyone if a patient confides important things in the person running the bar that day – whether the latter is a caseworker, a nurse, a “simple” intern or another patient – and does not say much to the psychiatrist during the next day’s consultation, for the team will find a way to link up information given in a scattered manner.

There are numerous workshops: sewing, music, reading, a magazine, a film club, writing, drawing and painting, radio, relaxation, leatherwork, jam making, cultural outings… but patients can also come along just to spend a moment there, to have a coffee, to feel welcomed and supported, caught up in the atmosphere of the place. Indeed, the object of a workshop is not an end in itself, it is often only a pretext, an invitation not to stay shut in at home, to reconnect with the world and reshape their bond with it.

Vu par Pierre Delion, psychiatre, professeur des universités-praticien hospitalier à L'Université Lille-II et psychanalyste

Nicolas Philibert nous avait déjà conquis avec ses films précédents. Que ce soit « La moindre des choses » (1997) retraçant la vie quotidienne de la célèbre clinique de la Borde fondée par Jean Oury, « Etre et avoir » (2002) racontant une année scolaire dans une classe unique dans la campagne profonde de Clermont Ferrand, ou encore « La maison de la radio » (2013) en mettant des images sur de nombreuses voix connues et reconnues, il a toujours su nous captiver par son style et sa présence auprès de ceux qu’il filme avec tant de tact que d’intelligence.

Dans son dernier documentaire, couronné d’un Ours d’or à Berlin cette année, il nous fait découvrir un lieu magique de la psychiatrie parisienne, la péniche du pôle Paris centre-Charenton, qui porte ce nom énigmatique, l’Adamant, signifiant le cœur du diamant.

C’est l’histoire de la rencontre entre un cinéaste, sa petite équipe et des patients malades mentaux qui viennent chaque jour ou presque sur ce bateau amarré à un quai de la Seine, animé par des soignants qui les accueillent de façon tout humaine, se démarquant ainsi du délabrement et de la déshumanisation de la psychiatrie contemporaine. Cette équipe y pratique une psychothérapie institutionnelle, déjà à l’œuvre dans La moindre des choses, en appui sur une vie quotidienne partagée autour de repas, de cafés, de cigarettes, d’activités culturelles diverses (cinéma, peinture, dessin, poésie, journal, ballades, gestion du bar,…) et de nombreux espaces interstitiels imprévus facilitant les rencontres inopinées et fécondes. On croise dans ce film émouvant de nombreux visages, souvent ravagés par les angoisses archaïques, pas celles du névrosé occidental poids moyen, mais celles qui évoquent l’enfer du monde interieur de personnes gravement troublées. Ces visages montrent que, contrairement à ce qui se dit pour masquer la réalité de la maladie mentale, les angoisses traversées sont les signes d’une urgence vitale quotidienne pour chacun d’eux, et nous assistons avec reconnaissance au miracle de leur résolution partielle dans l’échange entre eux et avec ceux qu’ils côtoient dans la péniche, aussi bien les soignants que les autres patients. Leur regard pénétrant est celui d’êtres fragiles qui voient la mort psychique en face et décident de ne pas la suivre. Un des patients décrit par le menu son délire persécutif terrible qui l’amène à se fâcher avec tout le monde, y compris avec la part de lui-même qui le retient de se jeter dans la Seine, à l’image de l’héroïne de l’Atalante de Jean Vigo, et il souligne avec vigueur l’importance de ses médicaments qui lui permettent, dit-il, la communication avec autrui. C’est le même qui ouvre le film avec une interprétation poignante d’un rock de Téléphone, groupe pour lequel il éprouve une passion folle…Un autre patient s’installe au piano et interprète une chanson qu’il a écrite avec un talent qui le mène aux confins de Léo Ferré. Frédéric, qui possède une culture époustouflante, soigne son délire ancien en côtoyant avec grâce Vincent Van Gogh, son frère, Jim Morrisson et Pamela, et bien d’autres encore.

Nous partageons avec eux ce que l’effet psychothérapique peut produire lorsqu’il se construit dans les rencontres multiples et non programmées, à partir des compétences que ces patients trouvent en eux au contact des autres, et qu’ils arrivent à faire fructifier à force de prétextes divers tels que les nombreuses réunions de préparation d’un anniversaire des dix ans du club cinéma, de gestion du bar de l’Adamant, de fabrication de confitures, de discussions sur l’organisation de la journée, bref, tout ce que la psychothérapie institutionnelle a inventé à partir d’une relecture du concept freudien de transfert à l’aune des psychopathologies psychotiques, à savoir la nécessité de disposer d’institutions. En effet, la psychiatrie, notamment pour les personnes les plus en difficulté, ne peut se réduire à l’exercice du psychanalyste en cabinet ni à celle du psychiatre biologiste avec ses protocoles prédéterminés, attendant des seules neurosciences le grand soir de la découverte du gène de l’autisme et de la schizophrénie, ou encore à celle du réhabilitateur psychosocial avec ses visées rééducatives et normalisantes, séduit par les mirages de l’éducation thérapeutique. Non, elle a besoin d’institutions vivantes, accueillantes et souples, qui n’ont pas d’a priori sur les personnes gravement touchées par la déshérence psychopathologique, mais qui acceptent de traverser les épreuves de la vie quotidienne avec elles, et pensent les soins a postériori, à la lumière des expériences vécues ensemble, de leurs impasses et de leurs ouvertures, de leurs apories et de leurs avancées notables.

Nous sommes là très loin de tous ceux qui, parmi nos décideurs, pensent qu’il faut contraindre la psychiatrie à suivre des règles d’asepsie, certes pertinentes en chirurgie, mais nuisibles dès lors qu’il s’agit de restaurer les relations avec autrui.

Nous sommes là très loin de l’importation dans le domaine des soins d’un management prévu initialement pour l’industrie alors qu’il s’agit essentiellement du fonctionnement des équipes au contact de la souffrance humaine.

Nous sommes là très loin d’une hiérarchie basée sur les statuts professionnels quand il s’agit au contraire de faciliter les émergences permises par une ambiance phorique, au plus près des vulnérabilités et des potentialités de chacun.

Les responsables de l’Adamant ont compris qu’il fallait un lieu insolite, esthétique et chaleureux pour y exercer une psychiatrie digne de ce nom. Et plutôt que de suivre aveuglément les recommandations d’une prétendue haute autorité en psychiatrie, ils ont accepté l’idée que les soignants se laissent guider par leurs intuitions dans un accompagnement authentique de chaque patient et ont tout mis en œuvre pour en favoriser l’augure. Il arrive trop rarement que les tenants du pouvoir comprennent qu’ils ne sont pas là pour imposer un fonctionnement jugé adéquat à leurs yeux de non spécialistes, mais bien plutôt pour donner les moyens aux artisans que nous sommes résolument, d’accomplir ce pour quoi ils travaillent dans ce domaine si complexe, et de redonner du sens à des professions sinistrées. Et les résultats ne sont pas pures supputations, ils sont là, sous nos yeux, en plein Paris, à deux pas des ministères de la Santé et de Bercy, qui continuent de nous imposer une politique de la psychiatrie qui a perdu l’essence même de sa raison d’être.

Le documentaire de Nicolas Philibert est, de ce point de vue, un outil essentiel pour rappeler comment et pourquoi les psychiatres et leurs équipes avaient inventé la psychiatrie de secteur comme condition de possibilité d’exercer une psychiatrie publique digne de ce nom et la psychothérapie institutionnelle comme discours de la méthode des soins psychiques. Il ne s’agit pas d’opposer les découvertes de la génétique et des neurosciences à celles de la psychopathologie transférentielle, tout simplement de les articuler pour en tirer les avantages attendus et les mettre au service des patients, notamment des plus gravement atteints. L’Adamant nous démontre qu’il existe encore de tels lieux. Sachons en faire fructifier la praxis et revenir à une psychiatrie humaine dans tous les services où elle risque de disparaître avec perte et fracas, malgré les discours lénifiants de nos décideurs. Merci à Nicolas Philibert et à son équipe de nous délivrer avec sagesse et sérénité un message d’espoir à un moment où les patients en ont particulièrement besoin. L’Adamant est bien décidément le cœur du diamant.

Press kit

How did this film come about?

I first heard about the Adamant a good fifteen years ago, when it was still just a project. At the time, the clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst Linda de Zitter, to whom I have remained very close since the filming in 1995 of Every Little Thing at the La Borde psychiatric clinic, was involved in the exciting adventure of its creation: for months, patients and carers had been meeting with a team of architects to define its key components. And what started out as a utopian dream finally came true.

Years later, around seven or eight years ago, I had a first opportunity to go to the Adamant. The Rhizome workshop invited me to come and talk about my work. Rhizome is a conversation group that takes place every Friday in the library. From time to time, five or six times a year, a guest is invited: a musician, a novelist, a philosopher, an exhibition curator… That day, I spent two hours in front of a group that had prepared for my visit by watching some of my films and continually forced me out of my comfort zone. Since starting out as a filmmaker, I have had many opportunities to speak in front of an audience, but this time it left me particularly invigorated, spurred on by the remarks of the people who were there. The wish to make another film in the world of psychiatry, to “see who I am elsewhere”1, had been with me for a long time, and that day reinforced my desire. Some patients and carers certainly had very high expectations! However, I would need to wait a few years before beginning because I was focused on another project.

Why, years after filming at the La Borde clinic, did you want to make another film in the world of psychiatry?

I have always been very attentive to and very interested in psychiatry. It is a world that is both disturbing and, dare I say, very stimulating, insofar as it constantly forces us to think about ourselves, our limits, our flaws, and the way the world works.

Psychiatry is a magnifying glass, an enlarging mirror that says a lot about our humanity. For a filmmaker, it is an inexhaustible field.

Moreover, in the last twenty-five years, the situation of public psychiatry has deteriorated considerably: budget cuts, bed closures, lack of personnel, demotivation of the teams, dilapidated premises, carers snowed under with administrative tasks and often reduced to the role of simple guards, the return to isolation rooms and restraint. This decline was undoubtedly an additional motivation. There has never been a golden age, but we hear from all sides that psychiatry is now at the end of its tether, completely abandoned by the authorities. It is as if we no longer wanted to see the “mad”. They are no longer discussed except through the prism of their dangerous nature, which is most often fantasized. The security-oriented rhetoric of a large part of the political class and a certain press who unashamedly exploit a few isolated incidents is obviously not unrelated to this. In this extremely devastated context, a place like the Adamant seems a little miraculous, and we have to wonder how long it will last.

What you say about the degradation of psychiatry is not perceptible in the film. Does this mean that the Adamant has escaped the devastation that has struck the sector?

The Adamant has managed to remain a lively and attractive place, both for patients and carers, because it does not rest on its laurels. It is a place that is constantly in touch with the outside world, open to everything that is happening, and which welcomes all kinds of contributors. Our filming is an enlightening example of that.

Moreover, it is a place that strives to do work on itself, in line with “institutional psychotherapy”, that current of thought with a rather barbaric name that prescribes that, in order to care for people – and to keep desire alive – the institution must be cared for, that it must fight relentlessly against everything that inevitably threatens it: repetition, hierarchy, excessive verticality, withdrawal, inertia, bureaucracy… And the place itself is very beautiful, which counts for a lot: the spaces, the materials, its location, the proximity of the water, when most similar units, without mentally ill that is so degrading. The basis is the human relationship. It is everything that is set up, everything that is attempted, using various tools, without excluding any, so that the encounter may take place. There is no recipe, no magic wand. “Human” psychiatry – a pleonasm? – is one that fumbles, that finds tailor-made solutions. It considers patients as subjects, recognizing their singularity without seeking to domesticate it at all costs.

What was your state of mind when you started filming?

Every Little Thing helped me a lot. It took me a long way, allowing me to rid myself of a certain number of preconceptions. At the time, I was very hesitant about making a film on psychiatry: how could I film people brought low by suffering without exploiting them, without abusing the power that the camera inevitably gives to the person holding it. People for whom the sight of a camera, a boom or a microphone can nourish a feeling of persecution, provoke delirium, decompensation, a performance. How can we avoid making a spectacle of suffering, avoid falling into folklore and complacency? But once I was there, the encounters changed everything. The answers came from the patients themselves. They encouraged me to confront my scruples and doubts, and helped me to overcome them. Some said: “Are you afraid of exploiting us? What are you thinking? We may be crazy but we’re not stupid!”

Today, in the age of social networks, where we are encouraged to say and show everything, these same questions are no less relevant. Films must keep their secrets, keep the questions open. It is important for me to resist this injunction, this call to make “everything visible”, into which our world is inexorably sinking.

What were your initial resolutions?

Above all, I wanted to feel free and not impose anything on myself. Not to have to worry too much about the film’s architecture, convinced that the unity of place, along with the identifiable and recurring “characters”, would be enough to constitute the cement and allow for undisciplined construction.

Following characters, losing them, finding them later, filming a meeting, a workshop, the greeting of a newcomer, filming private conversations, informal exchanges: at reception, at the bar, in the kitchen, on the deck, between two doors, catching an exchange on the fly, a monologue, a play on words, and recording all these little details that one might find trivial, eccentric, anecdotal or simply idiotic, and that would become the very fabric of the film we were making.

I’ve always liked to improvise, and over time, improvisation has become an ethical necessity for me. Above all, explain nothing. Avoid subjecting the film to a programme, to pre-existing ideas that have to be expressed. Track down any hint of intentionality.

Moreover, nothing ever goes as planned, the presence of a camera always reshuffles the cards. Making a documentary means dealing with the accidental, with everything that escapes predictions. The most beautiful scenes are often those that come about by surprise, without premeditation. Sometimes it is enough to be there, attentive to the surroundings, and to believe in it enough for this place to become a setting, these men and women the characters of a tale, these seemingly insignificant actions authentic stories. For me, the most important thing is to have a solid starting point, like the promise that something will blossom. “I write my books to find out what’s in them,” used to say the writer Julien Green. I could adopt that line for myself.

How did you go about getting yourself accepted, along with the presence of a camera?

Before you can reap, you have to sow: gain the trust of those you want to film. Luckily, some of the nursing staff and several patients knew a few of my films. That helped. I took the time to explain my project without trying to conceal any of the hesitations I might have, sharing them on the contrary with everyone. This also helped. They understood that if I was demanding, that was first and foremost in relation to myself. Finally, they saw that I was ready to let myself be carried along, that the film would built up according to circumstances, contingencies, availability, and not from a position of superiority. In the end, there was a fairly spontaneous acceptance. Curiosity too. And for many, the desire to be part of it. Some people asked not to be filmed, without being hostile to our presence.

How long did shooting last and how much footage did you accumulate?

I had planned to take my time, but if shooting goes on too long it can become intrusive. So you have to disappear now and then to give people a break. Hence the filming over several stages, which ended up being spread out over seven months – from May to November 2021 – because Covid got involved… not counting a few isolated days in early 2022. With the same idea in mind – to avoid being too invasive – I often shot alone. When the team was complete, there were four of us: a sound engineer, a camera assistant, an intern, and me behind the camera. To film a meeting, a workshop, we had to use a boom, and on certain days we had to shoot with two cameras, but for more intimate situations I managed alone. I probably shot alone half the time. In the end, I had around one hundred hours, maybe a little more. That’s a lot. But shooting is not about gathering as much material as possible and thinking “we’ll see later, we’ll see when we edit”, otherwise there would be no reason to stop. Shooting means already beginning to build up the film, to make associations, to look for correspondences, to put situations into perspective. So it means already thinking about editing.

How did you construct the film during editing?

I had to find a balance between the moments of daily life, with everything that can mark it – workshops, meetings, the bar, informal exchanges – and more intimate moments in which a person confides in me a little of his or her story, while ensuring the unity of the whole. Another challenge was to make the collective exist, as it is so important in this place – from a therapeutic point of view – without the audience feeling lost. I therefore needed a few recurring “characters” to whom we could become attached. Another balance to be found.

I was of course very keen for the audience to hear the patients. Their sensitivity, their lucidity, their humour sometimes. Their words, their faces. Their vulnerability, which would encounter ours here and there. I wanted us to be able to identify with them, or at least recognize what unites us, beyond our differences: something like a common humanity, the feeling of being part of the same world.

Once again, I attached great importance to voices, accents, language, speaking and listening. His Master’s Voice, In the Land of the Deaf, Every Little Thing, La maison de la radio, Nénette… my films are all variations on language, with gaps, fullness and silences. It’s all about rhythm and sound.

In the film, the carers seem to be more or less in the background. We can’t always tell them apart from the patients...

Indeed, there is nothing to identify them as such at first sight, as they do not wear white coats, do not have syringes in their hands… In short, they do not conform to the clichés. Moreover, I have kept nothing of the daily meetings they have with each other, nor anything that resembles explanatory speeches by them. Even so, they are not in the background: we see them talking with patients, conducting workshops (drawing, accounts), co-moderating meetings, in brief they play their part completely, attentive to each other, often discreet but very much there. We could say that caring is first and foremost caring for the atmosphere, it is not frontal, it is subtle, often imperceptible, it goes through a thousand and one details. A great Japanese fashion designer used to say: “The most important thing in a garment is what makes it stand up while remaining invisible, its hidden side”.

The fact of not distinguishing between patients and carers from the outset can be a little confusing, I agree. It’s sad to say, but today, in these times of inward-focused thinking, it’s as if we need to put people in boxes, to reassure ourselves by knowing precisely who is who, who does what. That guy over there? A schizophrenic! And that one? A nurse! But the Adamant – like La Borde, La Chesnaie and other places – has a different philosophy. Many activities are co- hosted there. The carers do not spend their time draped in their status, concerned about appearing for what they are. The border between carers and cared for, if there is one, is not set up as a bulwark. By adopting this logic, the film places the viewer in the position of having to get rid of certain clichés. It is an assumed political position. It makes things more complex, when today everything pushes us towards simplification.

The film ends in fog…

It was an idea I had very early on, which I really wanted to keep. For two months I set my alarm clock for five in the morning to watch the weather. Unfortunately, in Paris itself, fog is a virtually non-existent phenomenon. I ended up capturing a little of it, but I would have liked it to be much more enveloping. Like a sort of homage to haziness. A blurring of the edges. In other words, of the sacrosanct normality.

This film is the first part of a triptych. Can you say a few words about the other two?

I shot the second part at Esquirol in the two intra-hospital units that come under the Paris Centre group. It will be called Averroès and Rosa Parks, since those are their names. It is largely based on individual interviews between patients and psychiatrists. Some of the patients filmed on the Adamant, andothers, will be included. It is currently being edited.

The third film will be a collection of home visits to patients by carers. The final title has not yet been chosen. Once again, there will be some familiar faces. Most of the film has been shot, and partly edited. But I must insist on one point: the three films are completely autonomous. You don’t need to have seen the first one to see the next ones. You can see them in any order, or only one, etc. What they have in common is that they are set in the Paris Central Psychiatric Group, but they are three very distinct films. They will be released in theatres within a few months of each other. I had set out to make only one, but things turned out differently.

Paris, January 2023

- October 31, 2023

Nicolas Philibert won Berlinale’s highest prize this year for his gently observational documentary about a psychiatric daycare centre, which runs from inside a boat called The Adamant moored on the banks of the Seine in central Paris.

Art therapy is at the core of this humane institution that opened its floating doors in 2010. It’s a place where nurses and patients are indistinguishable within an atmosphere of creative discovery and delicate psychological probing. ‘People have gone in circles for thousands of years trying to pin down what can be deemed art, who’s allowed to do it and what determines its value. For all of us, you just know it when you see it,’ said jury president Kristen Stewart explaining why On The Adamant was awarded the Golden Bear.

I sat down for a long, deep and beautiful conversation with Philbert ahead of On The Adamant’s UK premiere at the London Film Festival in October. In the same way that the film gives a preview of a softer world, so too do the thoughts of its director.

ONE CONNECTION BETWEEN ON THE ADAMANT AND YOUR PREVIOUS FILM EVERY LITTLE THING (1997) IS THAT CREATIVITY IS SHOWN TO BE OF HUGE PERSONAL AND COMMUNAL VALUE. WHAT DO YOU BELIEVE THAT MAKING AND WATCHING ART CAN DO FOR LONELINESS AND THE HUMAN SOUL?

We live in a very dark, violent world that’s constantly subject to acts of barbarism and war. In the midst of this, all forms of art – whether it be music, dance, film, fine arts – allow us to not only survive, but to live and to thrive. That goes for you, me and everyone. Even if you’re not an artist, as the audience member who goes to watch a film or a play or a dance show, it helps you deal with the darkness of the world.

PEOPLE, ESPECIALLY FRAGILE PEOPLE, CAN BE DEPERSONALISED BY THE WEIGHT OF THE WORLD AND MAKING OR APPRECIATING ART IS A SPACE FOR A PERSONALITY TO COME BACK TO LIFE. IT’S INTERESTING BECAUSE BOTH YOU AS THE FILMMAKER, AND THEY AS THE PATIENTS, ARE MAKING ART TO SURVIVE. DID YOU HAVE THESE DISCUSSIONS WITH THEM ABOUT YOUR HOPES FOR THE FILM?

When shooting the film we had many discussions, always. As you could see on The Adamant they have a lot of workshops: music, film, radio, drawing and painting, sewing, etc. The idea is not to make artists out of them. These workshops are used as a tool. The issue with the people on the boat lies in their relationship with the rest of the world. The illness, so to speak, is within this link, so what this psychiatry tries to do is to repair that relationship, to help their link to the rest of the world. This can be done through the workshops, but the act of sharing a coffee with someone and speaking, this is how you rebuild those links.

CINEMA ALSO DOES THIS FOR PEOPLE WHO ARE ‘WELL’, IT MAKES A SPACE FOR US TO TALK ABOUT THINGS WE CAN’T OTHERWISE. SO WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE ART AND ART APPRECIATION OF THE PEOPLE IN THE ADAMANT AND THE ART OF PEOPLE WHO ARE CELEBRATED AND RECOGNISED AS ARTISTS?

I try not to erect barriers between artists and psychiatric patients. If there are barriers they are extremely porous. Both artists and patients are very sensitive people. It’s a complex question as a lot of people are on the frontier of what we consider normal. I think we can say about some artists that they have made a success out of that folie.

I AM NEURODIVERGENT AND FEEL A DEEP KINSHIP TO THESE PEOPLE AND A HUGE RESPECT FOR HOW FRANK THEY ARE ABLE TO BE ABOUT THEIR PLACE IN THE WORLD. IT FEELS LIKE THAT KINSHIP AND RESPECT IS IN THE DNA OF THE FILM. WERE THERE ANY PARTICULAR INSIGHTS OR MOMENTS THAT FELT LIKE YOUR TRUTH ALSO?

Documentary is always the result of a specific outlook, it’s never the full reality. Like any other filmmaker, I’ve made some choices to film this and not [that], so it is from a subjective point of view. Independently of that, the film was constructed and born out of the relationship that I developed with the patients. When I started I had no plan, no program, no intention. The starting point of any new film is never to share a specific message (in this case about psychiatry). So when I start out I don’t actually know what the film will achieve or what I will be saying. I improvise with the dynamics with the people who are there with me. My work consists of building confidence, this is the basis of everything.

IT FEELS LIKE THEY REALLY TRUST YOU WHEN THEY’RE TALKING TO THE CAMERA. HOW LONG DID YOU SPEND ON THE ADAMANT BEFORE YOU STARTED FILMING?

I [went] there a few times, but I’m not one who needs to spend three weeks or three months just watching or trying to become invisible. I’m not trying to make them forget that I’m there. I’m trying to have them accept my presence. I don’t want to be a filmmaker that becomes transparent. Unlike a lot of documentary filmmakers where they say to their subject, ‘Please pretend that I’m not there’, I say the opposite.

IS THAT AN ETHICAL CHOICE?

It is an ethical thing, I’m there ‘with’ the people not ‘about’ the people.

DID YOU HAVE ANY ETHICAL CONCERNS ABOUT SECURING CONSENT FROM SUCH FRAGILE PEOPLE TO FILM THEM AND, IF SO, HOW DID YOU WORK THROUGH THOSE?

It’s a complicated answer, indeed, and it begs for a nuanced reply. Firstly, I only filmed people that agreed to be filmed and I always explained, ‘You can accept or refuse to be filmed. If you don’t want to be filmed, no problem. Don’t feel guilty about that. You are completely within your rights.’ That was the beginning of building confidence. But it’s not enough for someone to express their willingness to be filmed. I try to film people when they are conscious of what’s happening, conscious that they are filmed. Maybe when you are there you meet somebody who says, ‘Okay, I’m happy to be filmed’ and suddenly they would make a bit of a show in front of the camera, expressing some sort of eccentricity, and we’re not sure if they’re fully conscious of the choice they made by saying yes.

So someone in that state of mind, a bit delirious, even if they accept to be filmed, they wouldn’t have given their full reasoned consent and therefore it wouldn’t feel right for me to film them. But it’s a blurry line because what does it really mean to be fully conscious of the consequences of being filmed? So, I try to get as much information as I can. It’s not enough to say, ‘Are you okay if I film you?’ The people that we film need to be fully conscious of all the repercussions of being filmed, of everything that’s at stake, so I explained that the film would be out at the cinema, on various platforms, on DVD perhaps, so they’re fully conscious of where this will end up. I’ve been told that I’ve ignored some sides of this subject matter. I’ve not filmed people rolling around on the floor screaming, moments of madness, because psychological suffering is not entertainment. If someone’s rolling on the floor suffering, I’m not going to film them.

THERE ARE LOTS OF CINEPHILES ON THE ADAMANT, SO WHAT DID IT MEAN TO THEM WHEN YOU WON THE GOLDEN BEAR?

The staff and the patients – I would prefer to say the passengers – discovered the film after Berlin as Berlinale wanted exclusivity. We couldn’t show them the film earlier, so just after Berlin we [arranged a] screening in Paris. They all came, and at the end the lights came up and one of the passengers came to me and offered me his teddy bear from his childhood. I was deeply moved. Such a present, you know? I don’t want to speak for them, but I do think that somewhere they consider it to be their film. They’ve been very touched by it. They are used to other people looking at them with mistrust and considering them potentially dangerous, and with this film, it’s a way for them to find their dignity.

I WAS VERY MOVED BY THE MAN WHO SAID ‘OTHERS CAN LOOK AT US ON THE METRO, WE HAVE SLIGHTLY BROKEN FACES MAYBE. PEOPLE ALWAYS GIVE US CURIOUS LOOKS’. THE FILM SHOWS THAT THE PASSENGERS ARE CONNECTED TO REALITY, YOU KNOW?

Suffering from psychological issues does not necessarily mean that we’re not aware of what’s going on around us. Watching the film, it’s very impressive how [the] people I filmed are very lucid when it comes to their own suffering. Nobody can talk about what they’re suffering better than themselves. Yes, they go through moments of darkness, moments that are very unbearable for them when they hear voices, and in those cases often they retreat, they stay at home. The instances where we see them where they are on The Adamant tend to be moments where they’re more at peace.

A PASSENGER AT ONE POINT SAYS THAT MENTAL-HEALTH ISSUES CREATE DIFFICULTIES WITH FAMILY, AND IT FEELS LIKE THE ADAMANT IS A FOUND FAMILY. DO YOU KNOW HOW SUCH A PLACE MANAGED TO EXIST?

The Adamant is both an exceptional place and a place that’s not so exceptional, and I’ll explain why. Thankfully, across France, there are many psychiatric departments that practice this more humane type of psychiatry that treat patients like human beings and don’t reduce them to their illness. And I stress this last point because we’re currently in a situation where the psychiatric landscape in France has been devastated by things like funding cuts, lack of beds, nurses that are fleeing the sector because they can’t practice with dignity. Despite everything, there are still some professionals out there resisting. What makes The Adamant exceptional, really, is its location – the fact that it’s on the water. The architects who built it worked closely with careworkers and patients to design something that would be beautiful and therapeutic. Usually, places where psychiatry is conducted tend to be quite functional, ugly spaces. Patients and careworkers enjoy being in a space that is beautiful in a way that’s therapeutic, that’s calming; they are instantly happier being there. We’re all sensitive to the beauty of our surroundings, it affects our emotions.

IT SEEMS LIKE YOU MIGHT BE ON YOUR WAY TO BECOMING A QUALIFIED PSYCHOLOGIST WITH ALL THIS OBSERVATION… IS THAT OF INTEREST?

Many of us can have a caring role without necessarily being a care professional, so a filmmaker, or even another patient, might have a therapeutic role towards other people on the boat. Last Monday, a journalist from The Guardian came to The Adamant to interview me; he planned to stay for maybe one and a half hours, but he stayed for four hours. When he arrived, I introduced him to those who were [there]. We asked a patient if he’d show us round [and] we spent half an hour with [him] explaining how The Adamant worked, the workshops, the library and so on. Then we conducted the interview and I had to go home, but he remained there for another hour and a half just talking to the various patients about life on The Adamant. Unintentionally, he ended up having some sort of therapeutic role for them because he gave them a platform to express themselves.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR YOU?

On The Adamant is the first film in a triptych, originally unintentionally so. When I first went aboard I was just meant to make one film but was compelled to make a trilogy.

HAVE YOU ALREADY FILMED THE SEQUELS?

I just finished the second one last night. The Adamant is actually a day centre for the people living in the first four arrondissements of Paris. When they’re really unwell they’re taken to a hospital called Esquirol named after a great psychiatrist who lived in the 19th century, and the unit there caters for the people living in Central Paris. The second film is shot in two medical units inside the hospital, called Averroès and Rosa Parks. We meet again some of the passengers from The Adamant who have been hospitalised and we also meet new protagonists. The second film is based on conversations between psychiatrists and patients, beautiful conversations not only about the pills, but about anything. Aristotle or whatever. There will be a third film because when I was shooting on The Adamant I discovered that some young nurses sometimes go to visit patients when they have domestic problems, like electricity, so they go to their place to help them with repairs. The third film is built on a few home visits by these young nurses. We will go with Frédéric or Muriel, patients I filmed on The Adamant, into their places.

WHEN WILL WE BE ABLE TO WATCH THESE TWO EXTRA FILMS?

In France, they are supposed to be released in the first semester of 2024, but the third one is not finished. I still want to film one more visit. It’s partly edited but I still have some shooting.

ON THE ADAMANT IS OUT IN CINEMAS AND ON CURZON HO

Screen Daily - February 24, 2023

Nicolas Philibert climbs aboard the titular floating Parisian day centre for this warm documentary.

Moored on the banks of the Seine, the Adamant – a Parisian day centre for people with mental disorders – is a metaphor made concrete. It’s at once free-floating, separate from the city that surrounds it, and, at the same time, at the centre of the metropolis. In other words, it is a haven for people supposedly apart from the rest of humanity, yet whose troubles absolutely embody the fragility and complexity of the human condition.

Waving a flag for the positive possibilities of an empathetic, culture-centred approach to mental care

That’s the theme at the heart of On the Adamant, the latest film from French documentarist Nicholas Philibert, whose works – including In The Land Of The Deaf and Every Little Thing – have often presented empathetic studies of humanity from the perspective of marginalised communities. While current tastes in documentary may not be as receptive to the non-narrative as in the days when Philibert’s 2002 Être et Avoir (To Be and to Have) was an international success, his engaging and affirmative new film will be warmly appreciated at festivals and on adventurous outlets – anywhere, essentially, where people are interested in discovering other people.

The film was directed by Philibert in collaboration with clinical psychiatrist and psychologist Linda de Zitter, who was also involved in 1997’s Every Little Thing, and who is intermittently glimpsed on screen here. The Adamant, which opened in 2010, is a big boat-like structure, designed in consultation with patients. Inside the centre, which works as a day-time drop-in, different areas function as studios, meeting rooms, spaces for music and dance; there’s also a library, very visibly stocked with volumes of poetry. This is France, after all, and a belief in the centrality of the arts is very manifest at The Adamant – a key aim of which, the end titles note, is to keep the “poetic function” alive.

Those captions apart, there’s no commentary in the film, which substantially comprises individual portraits of Adamant patients, given space to present themselves in their own voices and on their own terms. A middle-aged man named François kicks off the film with a passionate rendition of ‘Human Bomb’, by French rockers Téléphone; later, in an informal moment on deck with psychiatrist Guillaume, he gives a somewhat manic but intensely lucid account of his condition and his views on psychiatry. Similarly articulate, but very much on his own wavelength, a young man explains his sensitivity to ‘negative vibrations’, while another fascinatingly describes his complex mental system of correspondences between things and words, in which, for example, a blue balaclava might evoke the word ‘purée’ and, in turn, thoughts of death.

Perhaps the most fascinating figure is Frédéric, a laid-back, dandyish man with a remarkable silky voice, who explains how the deaths of Van Gogh and Jim Morrison offer the key to his own family history, and accompanies himself on organ on an inventively rhymed number (“Rêveur ô rêveur, never say never!”) – one of the songs he says are dictated by his unconscious. While Frédéric is one of the people most at ease here, by contrast Catherine is a punk-coiffed elderly bohemian who addresses a meeting about her suggestion of leading t’ai chi classes. Her discourse quickly becomes a digressive outpouring of rage, but one to which the film gives the time it demands, with the patients throughout this film setting their own rhythms.

Philibert and his crew remain invisible presences, except for one moment when charismatic, voluble patient Muriel turns round and quizzes them about their lives. The film is more about character and human presence, as opposed to depicting the overall functioning of this institution, as per the more detached observational approach of the Frederick Wiseman school. Nevertheless, we get a strong sense of The Adamant’s functioning and its values, with arts and culture central as a vehicle for expression and self-realisation, as several patients attest. For cinephile viewers, a mark of this centre’s enlightened approach is that it has a film club showing works by Truffaut, Fellini and Kiarostami.

A rhetorical note in the closing captions makes it clear that Philibert is proposing The Adamant as something of a utopian ideal for psychiatric practice. There are certainly questions to be asked about whether he might have presented a more critical picture; you wonder whether Philbert filmed any moments of stress or conflict, or scenes showing the difficulties faced by staff – in the daily running of the place, or with funding, for example. But that would have made for a different film, and it’s clear that this one is waving a flag for the positive possibilities of an empathetic, culture-centred approach to mental care.

In keeping with this positive agenda, Philibert, himself heading the camera team, shoots primarily in warm colours, maintaining a sense of this singular structure as a warm haven and literally a safe space. The action stays moored within The Adamant, apart from some lyrical glimpses of a tree-lined quayside, and a brief sequence where patients visit a greengrocer’s to salvage discarded fruit from the bins – which one is tempted to see as a fond nod to a similar practice, as portrayed by Agnès Varda in The Gleaners And I.

The Guardian - March 1, 2023

Nicolas Philibert’s warm and sympathetic documentary about a boat for mental-health patients on the Seine is a worthy winner of the Berlin film festival’s Golden Bear

There was real justice in Kristen Stewart’s Berlin jury awarding their rop prize, the Golden Bear, to this excellent movie from the 72-year-old French director and lion of documentary film-making, Nicolas Philibert. His film is compassionate, intelligent and shrewdly observed; it is about a Paris landmark which has only been in existence for 13 years but which tourists and anyone with an interest in mental health should really come and marvel at. The Adamant is a floating day-care centre for people with mental disorders, permanently moored on the Seine just by the Charles de Gaulle bridge. The design is half Mississippi gamblers’ riverboat, half art studio, with an elegant system of automatically opening louvred windows which make the most of daylight. The staff offer counselling and art therapy through music, painting, craft, literature and cinema. The Adamant hosts its own annual film festival for which the patients choose the films. There is also a cafe and bar.

The vessel’s name, the Adamant, is interestingly old-fashioned, like calling it the Fighting Temeraire. But it’s appropriate. Everyone involved is determined that the French state should protect this kind of respectful, collegiate approach which treats patients as human beings.

The movie begins with a fascinating, even sensational setpiece: a patient, François, sings the 1979 pop song La Bombe Humaine by the French band Téléphone. His face is strained and flinching but his delivery is passionate and brilliant – it’s an example of “outsider art”, a blazingly real outpouring of emotion and talent which is partly occluded by his problems but also in some sense deepened and given meaning by them. Later this man will tell Philibert that he is grateful for the art-based therapies – but even more for his meds, without which he would be raving that he was Jesus and throwing himself in the Seine.

Other patients are given comparable therapies through drawing, painting and photography. One former patient even offers to host movement-based classes for the patients herself, although Philibert shows us that the staff, however forward-thinking, clearly feel a little cautious about this development. Another patient, a cinephile, talks eloquently about Jean Gabin and Lino Ventura and says of his fellow patients: “You have actors in here who don’t know they’re actors. It’s not medical. They’re actors without realising.”

Philibert is a director who has shown an interest in the philosopher Michel Foucault. Watching this documentary, I couldn’t help thinking that he must have had, somewhere at the back of his mind, the image of the “ship of fools” from Foucault’s History of Madness, as well as his work on the 15th-century poem of that name by Sebastian Brant, a Platonic satire which Foucault influentially reinterpreted as the key image of pre-enlightenment madness, of mad people allowed to wander or float where they would, before the rational age of punitive surveillance decreed they should be confined and studied.

The Adamant is very different: a non-ship of non-fools. The fact that it’s floating (though moored) signals that it is some way outside the traditional buildings and institutions of psychiatry. Its patient-clientele are day visitors; at the end of the sessions, they return to their residencies and hostels. They are treated like students although, as François says, it is the off-camera world of meds that makes this possible. Yet there is a gentle and very happy sense of freedom and possibility aboard the Adamant, and there is enormous warmth, sympathy and human curiosity in this film.

Variety - March 16, 2023

Kino Lorber has bought U.S. and Anglo-Canadian distribution rights to Nicolas Philibert’s poignant documentary “On the Adamant” which just won the Golden Bear at this year’s Berlin Film Festival.

Kino Lorber is planning a theatrical release later this year followed by a digital and home video release on all major platforms.

Sold by Films du Losange, On the Adamant takes place at a unique day-care centre for adults suffering from mental disorders. Located in a structure floating the middle of the Seine, in Paris, the center heals these adults with a blend of therapy, education, and culture rooted in music and the arts. The affecting documentary follows the team running the Adamant as they attempt to transform and uplift the lives for these people.

On The Adamant was directed, shot, and edited by Philibert, who is known for his humanistic approach to documentary filmmaking. He previously highlighted marginalized communities in Every Little Thing, In the Land of the Deaf and the arthouse hit To Be and To Have. On the Adamant is produced by Céline Loiseau, Gilles Sacuto, and Miléna Poylo.

“Nicolas Philibert is one of the great humanists of our time and his deep compassion, always evident in his work, shines brighter than ever in On the Adamant,” said Kino Lorber SVP Wendy Lidell, who negotiated the deal with Alice Lesort from Films du Losange. “We’re proud to add his latest work to our library of some of his very best films, and look forward to welcoming audiences aboard the Adamant so their minds can be opened and their spirits filled with wonder,” Lidell continued.

Philibert said he “[hopes] that the American public will be sensitive to this film in which [he has] tried to reverse the image that many have of the so-called ‘crazy’ who are too often marked by clichés which stick to their skin and designate them eternally as dangerous people when the vast majority are harmless.”

“I want audiences to recognize what unites us beyond our differences; although they may not be able to identify with the subjects, I hope they can recognize a common humanity, and a feeling of being part of the same world,” added the filmmaker.

Philibert said he was also “moved” by the fact that his film will be distributed by Kino Lorber “after many years of loyalty to [my] work.”

The acquisition of On The Adamant is the second high profile acquisition of late by Kino Lorber, who recently announced their acquisition of Scrapper, Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize winner directed by Charlotte Regan and starring Harris Dickinson and Lola Campbell. Both Scrapper and On the Adamant are set to play further in the festival circuit worldwide and will open theatrically later this year.

The Guardian - November 2, 2023

Director Nicolas Philibert had an unexpected triumph with On the Adamant, his film about a haven for people with mental health problems, named after the British pop star. We go aboard

The Adamant is both the setting and the star of the film that earned director Nicolas Philibert a surprise top prize at the Berlin Film Festival this year. But in his absorbing documentary, this institution – a floating daycare centre for people with mental health problems moored on the River Seine – somehow remains a bit of an enigma. Philibert’s slow, unassuming films don’t use narration, and in the absence of a contextualising voice you might assume that it’s a terrible idea to invite potentially vulnerable patients into a centre surrounded by water.

It’s only when you walk over the metal gangway and step into the ship-length reception area that the concept starts to make sense. Eric Piel, the psychiatrist who conceived of the Adamant and supervised its construction in 2010, insisted the centre should have as few walls as possible (the only doors I opened in my four hours there were to a therapist’s room and the toilet). The three-storey space feels surprisingly airy: sunlight bounces off the water and streams through the louvred windows, painting animated squiggles on to the wood-panelled walls. The screeching traffic on the three-lane Quai de la Rapée and the squabbling drunks under the Pont Charles-de-Gaulle sound far away. It’s a place that calms the nerves.

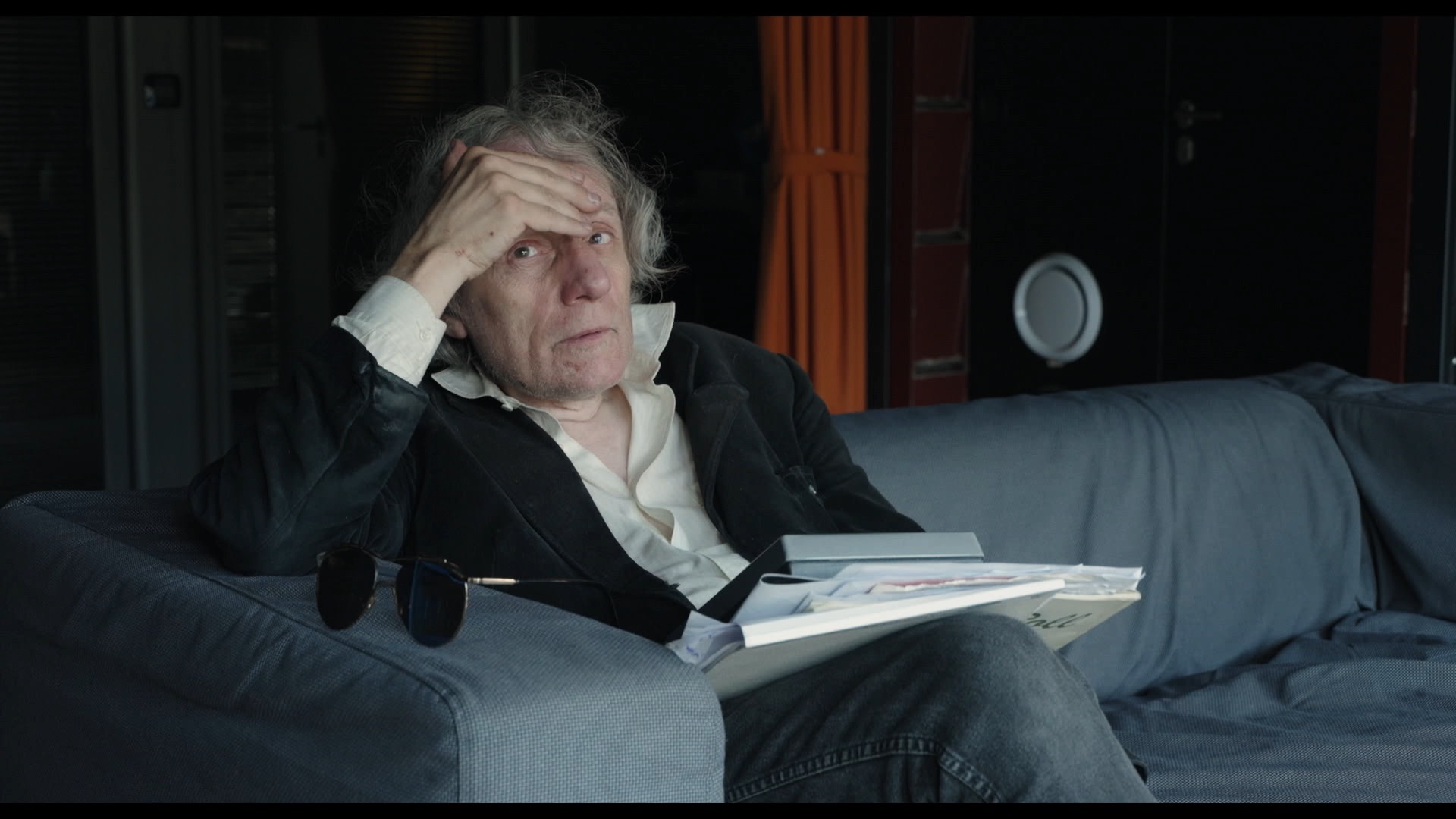

There’s also something about being on water that makes you more appreciative of your fellow human beings. As Philibert, a gently spoken, spiky-haired 72-year-old, walks me around the premises and a passing tour boat rocks the waves, I reach out to hold on to my guide. “We are in the very centre of Paris,” he says, “and yet we feel we are elsewhere. It’s a very soothing, healing place for everybody. Not just for patients but also for film-makers.”

The Adamant’s swashbuckling, Victorian-sounding name is symbolic of the centre’s determination to go against the currents of the times. “For more than 25 years, psychiatry in France has had to cope with money-saving measures and the merging of sectors,” says Arnaud Vallet, the state-funded centre’s lean and intense head nurse. “So the idea is to subvert this deadly economic logic.”

The 230 “passengers” (Philibert prefers this term to “patients”) are from Paris’s first four arrondissements. Having been referred by their doctor or therapist, they can drop by from Monday to Friday between 9.15am and 5pm. Most start with a strong coffee from behind a recycled shopfront counter. Afterwards they can partake in workshops for music, radio, drawing, painting or stained glass window-making, hosted by the centre’s 25 staff. The passengers cook together once a week and there’s a film club on Friday afternoons.

“If there is a mission here,” says Philibert, “it is to give people some kind of care. But that doesn’t mean they are going to be cured. The aim is to restore the passengers’ capacity to exist in life, in society, while keeping their individuality.”

Such an approach – enabling those with mental illness to participate in everyday life through meaningful activities, AKA occupational therapy – is hardly new. What makes the floating daycentre on the Seine different, though, is its stress on creativity. “The links the passengers have to the world are extremely fragile,” says Philibert. “Maybe the way to strengthen them is through activities that avoid boredom and keep their desire alive.”

During the Renaissance, mentally ill people in central Europe were reportedly boarded on to a “ship of fools” and effectively banished, sent on permanent voyages through the rivers of the Rhineland and Flemish canals. The Adamant, by contrast, is permanently moored in central Paris (a library sits where its engine would have been). By the end of the film, the centre comes across more like a cool private members club for gifted outsider artists than a place society wants to ignore. If you wish you could join the crew, you wouldn’t be the only one: during my visit, the novelist Marie Darrieussecq drops by to discuss a joint project.

The boat’s name, Vallet explains, is also in reference to Adam Ant, the British singer diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and there are rock star qualities to most of the regular visitors featured in the film. Take François, whose intense and brilliant rendition of Téléphone’s 1979 pop number La Bombe Humaine gives the film a showstopper in its very first scene. There’s also white-haired and stoical Patrice, who starts every day by penning a poem in the Adamant’s cafeteria – and ends it by typing up his verse at home. Then there’s Catherine, a dancer who is constantly limbering up on the boat’s balcony and eventually explodes with frustration that she isn’t allowed run her own workshop.

They all have troubles. “Only the meds stop me from thinking I’m Jesus,” says François, whose gap-toothed grin speaks of less happy times. But we never see the passengers in their troubled states. Instead Philibert’s interviews suggest that their ability to experience art in lateral, more intense ways could actually be a blessing. Alexis, a young man with a chinstrap beard, lives in a world of hyperactive associative thinking where every word begets an image. “Very tall thin men,” he says, “they remind me of ‘injection’. A bald man reminds me of an orange.” Another passenger is extremely sensitive to noise and can only calm the vibrations in his heart by listening to music.

If On the Adamant has a main character, it is Frédéric Prieur, who wears aviator sunglasses and bright shirts with tapered collars. When Philibert and I arrive, he greets us by the entrance like the ship’s captain, a rolled-up magazine functioning as his spyglass. Before he joined the passengers, Prieur was a student at a Paris university, but was struggling. “I was completely out of tune, out of space,” he says, fresh from a radio workshop. “I was nowhere and nobody. I was drowning.” On the ship, he spends most of his time immersing himself in culture, with an exhaustive, near-encyclopaedic focus on the 1970s and 80s. “Movies, science fiction, comics and pop music have helped me stay alive,” he says. “Otherwise I don’t know what I’d be – a wreck maybe.”

Philibert – best known for Être et avoir, his commercially successful 2002 documentary about a single-teacher school – has a long-running interest in people with mental illness and the places that look after them. In 1996’s Every Little Thing, he followed patients at a psychiatric clinic in the woods of the Loire Valley as they rehearsed their annual summer play. On the Adamant doesn’t have an equivalent structure: it loosely observes the ship’s passengers, many of whom remain unnamed, as they drop by but does not track where they come from or where they go next. “My idea,” the director explains, “was to be in synchronicity with the place and let myself be led by whomever I met. I didn’t come with a script or any message to deliver.”

This apparent artlessness makes the film’s critical success intriguing. After its shock win of the Golden Bear at Berlin, some critics suggested the jury only settled on this drama-free documentary as a compromise because they couldn’t choose between two more obvious contenders: German director Christian Petzold’s Afire and French New Wave veteran Philippe Garrel’s The Plough.

Such a view ignores On the Adamant’s evident appeal. European cinema may be in an existential crisis, struggling to prove its relevance amid the deluge of streaming platforms. But to the subjects of Philibert’s film, cinema and music still truly matter. The secret behind its success may lie in the fact that the Adamant isn’t just something of a life raft for its regular visitors, but for anyone who still cares deeply about art. One reason François’s rendition of La Bombe Humaine is so thrilling is that its artistry is unchecked and unfiltered. When he sings, eyes closed, that “the detonator is right there, next to your heart, the human bomb is you”, it cuts straight through. What if the passengers of the Adamant are better, purer artists than yourself, I say to Philibert. He replies: “It is true that the passengers are often very uninhibited. They say things in a very direct manner. They are unrestricted by convention. We normopaths no longer know how to do that.”

On the Adamant is released in UK cinemas on 3 November

Little White Lies - 18 avril 2023

French documentarian Nicolas Philibert returns with a gentle, deeply moving chronicle of a floating hospital in Paris.

As the grand finale of her stint as head juror for the 2023 Berlin International Film Festival competition, Kristen Stewart made the bold and increasingly common decision to award the top prize to a documentary. Yet as French veteran documentarian Nicolas Philibert sauntered up the stage to collect his gong, many in the audience were left a little puzzled – what on earth is this movie? Did anyone actually manage to see it? And, more importantly, can anyone affirm its greatness?

Well, out of the long, pale shadow of the limelight, we can now say that this is and extremely tender and poetic film which offers a careworn utopian vision of modern healthcare in the form of L’Adamant – a decommissioned steamship which has been moored at the Quai de Rapée on the Seine since 2010. Fans of Philibert’s 2002 breakthrough film, Être et avoir, which chronicles the daily classroom activities in a country school, will find much to love in this new one, which adopts a similar, deceptively rambling structure and a tone of unapologetic, non-oppressive empathy with its subjects.

Though L’Adamant is classed as a hospital, it more closely resembles a floating community centre where white lab coats are done away with and a homely type of equality takes over. The visitors take things at their own pace, and there’s a focus on arts and crafts as the locus for not so much rehabilitation, but a way in which engenders a level of calm which, itself, allows people to open up about themselves and their troubles. Though we can often deduce some stifled emotions through the artworks themselves, such as one patient who draws a smiley praying mantis with a pink bowtie.

Philibert doesn’t spend too much time trying to give a sense of the routine, or create a document of how this unique institute functions. Instead he is more interested in the people and, with his careful approach to his subjects, allows them to open up in a way that is natural for them. And so rather than the camera acting as its own device for interrogation, it is instead an eye for which the people can merely sit and, if they so chose, just look at their own reflections for a bit. Or, in the case of one chap, perform an incredible song with lyrics that would’ve made Serge Gainsbourg jealous.

L’Adamant is not a new age experiment or a space to test out cutting-edge curative techniques, it’s just a venue which values security, empowerment and freedom. As such, it’s clear that Philibert perhaps sees his film as a positive advertisement for more rudimentary but humanistic methods. The sense of responsibility that is stoked by everyone coming together and, say, making jam, or organising a film festival, seems, on this evidence, to offer a path to contentment.

But what’s most important here is how Philibert captures the patience of the nurses and attendants, who never ever interrupt or talk down to the people whose conditions and wellbeing are L’Adamant’s raison d’être. Formally, this is not reinventing any wheels, but it’s more impressive for what its maker doesn’t do more than what he does.

The artsdesk.com - November 4, 2023

Berlinale prize-winning portrait of an innovative approach to people living with mental illness

On the Adamant is an endearing documentary by the French director Nicolas Philibert, best known here for his 2003 film, Être et Avoir, a portrait of a single-room school in the Auvergne.

This time around, Philbert has placed his camera on the Adamant, a purpose-built barge permanently moored on the Seine in Paris. It’s a drop in centre for city dwellers battling with mental illness – a place where sessions of art therapy, communal cooking and mediated group discussions help troubled people from falling further into despair.

Philbert’s style is to eschew narration or captions, preferring the audience to get to know the characters who come to the boat without introduction or explanation. We meet François first, who gives a heart-felt rendition of the ‘70s hit, The Human Bomb. The song’s lyrics about alienation, a broken heart and an easily triggered temper obviously resonate with François.

We meet another regular patient who loves to dance and is frustrated that despite the co-operative ethos, she can’t run her own session for others suffering with their mental health. Patients question the film crew about their equipment. There’s an acknowledgement that their presence is giving them a chance to show the world how they live and who they are. Philibert isn’t that interested in the motivations or identities of the psychiatrists, therapists and social workers who keep the Adamant afloat, preferring to concentrate his gaze on the individuals who find sanctuary on board the barge. There are real charmers among them, including Frederic, who writes and delivers songs on the fly and compares himself with Jim Morrison and Vincent van Gogh.

We are not given case histories or diagnoses but it’s obvious that some of the regulars have learning disabilities and/or autism while others have experienced trauma or emotional abuse that have led to their battles with mental illness. These are fragile people for whom the Adamant offers support, validation and a refuge.

Following in the observational spirit of directors like Frederick Wiseman, Agnès Varda and the Maysles brothers, On the Adamant steers clear of making the barge’s regulars into objects of pity or freakish fascination. Filmed over a considerable period, we see the seasons change and visitors to the boat fluctuate in mood.

It’s not until the very end of the documentary that we learn how the Adamant is funded. A caption tells us it opened in 2010 and is overseen by a psychiatric hospital who provide the staff and facilities. Cuts mean that the Adamant’s future is precarious. Philibert’s film, which won the top prize at the Berlin film festival, should help ensure its survival.

The veteran documentarian’s meditative approach to film-making, relying purely on observation, can be a little frustrating journalistically – I wanted to know how the Adamant dealt with difficult service users, the ones struggling with unmanageable addictions or aggressive behaviour directed at themselves or others – but apart from that caveat, this is a warm, gently funny and very moving documentary. On the Adamant is the first in a trilogy of documentaries Philibert has planned about the treatment of mental health patients; I look forward to the next two films.

The Irish Times - November 3rd, 2023

When Kristen Stewart’s jury at this year’s Berlin International Film Festival awarded the Golden Bear to On the Adamant, nobody looked more astonished than the film’s director, Nicolas Philibert. Arriving two decades after the French director came to international prominence with Être et Avoir, the new documentary offers a similarly considered depiction of an unusual psychiatric facility.

“I have a particular affinity with the people that you tend to meet in the world of psychiatry, maybe because they trigger something somewhere inside me, a small part of me that’s hidden. I wasn’t aware of this for a long time, but a few patients spark something in me,” he says. Philibert adds that, 28 years ago, he made another film inside the world of psychiatry – Every Little Thing, which chronicled a collaboration between staff and patients as they rehearsed for their annual summer play at La Borde psychiatric clinic in the Loire Valley.

“I was initially very reluctant to make it. The idea wasn’t mine. It was a friend who encouraged me to explore this world. I had a lot of scruples. I was very conflicted. My main concern was the idea of filming people and making their conditions into entertainment for others. And somewhere there was a fear that I might be contaminated. That maybe, if I went into that world, I wouldn’t get out. It was actually the patients that helped me make the film. They recognised and commented that I didn’t want to objectify them. So when I came to make On the Adamant, I didn’t have those fears and concerns. I know this world.”

For On the Adamant, the 72-year-old film-maker spent months aboard a barge anchored on the right bank of the river Seine in Paris. As ever, he never appears on camera and is seldom heard. His films are immersive experiences, although entirely different in tone and structure from those of his good friend Frederick Wiseman. Where the latter shoots for hundreds of hours in prisons and educational facilities to better understand institutional functionality, Philibert is compassionately committed to the people within his institutions.

The docked Adamant, his latest stopover, is a day centre for patients with a range of mental disorders, offering therapy, food and cultural outlets. The film opens with a quote from the pioneering educator Fernand Deligny – “If there are no gaps, where do you expect the images to go?” – and emerges through a series of encounters.