One of the most fabulous “combinations” of climbs ever achieved by a mountaineer: on March 12 and 13, 1987, Christophe Profit, 25, succeeded in his attempt to climb the three toughest north faces in the Alps, in 40 hours: the Grandes Jorasses, the Eiger, and the Matterhorn.

But beyond the coverage of this feat, we discover the sidelines, the story behind the project, the ups and downs of its preparation, and the personality of the man behind the climbs, a dancer on sheer rock faces, focusing all the energy and reflexes of life itself in his fingertips.

Photography Laurent Chevallier • Sound Olivier Schwob • Editing Marie Quinton • Original score André Giroud • Assistant directors Suzel Galliard, Serge Lalou • Production manager Françoise Buraux • Line producer Yves Jeannneau • Co-produced by Les Films d’Ici and Antenne 2 • With the participation of Millet.

Grand Prize, International Forum of Sporting Adventure Films, Hakuba (Japan), 1987 • Gold Diable, International Alpine Film Festival, Les Diablerets (Switzerland), 1987 • Grand Prize, World Festival of Mountaineering Film, Antibes, 1987 • Special Jury Prize, International Adventure Film Festival, La Plagne, 1987 • Grand Prize, Teplice Nad Metuji Festival (Czechoslovakia), 1988 • Silver Triglav, Kranj International Festival (Yugoslavia), 1988.

First TV broadcast: July 1987 / Antenne 2.

In 1986, fate smiles on me. The film that I have just made, “Christophe” causes quite a stir in the small world of mountaineering cinema: it receives awards in specialized festivals and is sold to several foreign TV stations. For some time now, “sporting adventure” films, as they are known, are booming as new disciplines are developed: paragliding, snow-surfing, canyoneering, rafting, snowboarding, barefoot climbing, bungee jumping, etc. The TV channels are following the trend. TF1, Antenne 2 and France 3 each devote a weekly slot to the phenomenon. This media effervescence creates a demand: more and more “adventurers” appear. To finance their projects, they seek sponsors who demand images in return for their financial support…

Mountaineering is experiencing the same upheavals. Every peak in the Alps has been “conquered” by every route possible, by every face and from every angle – in summer, in winter, single-handed, etc… Therefore, it is necessary to invent new challenges, resulting in this idea of “combinations”, which is going to experience an amazing boom in the eighties. Another new phenomenon is the appearance of the stopwatch. Until this point, the prestige lay in the difficulty of the ascent carried out, however long it took. But, for a few years now, a new generation of mountaineers is at work. They do not hesitate to tackle the most difficult routes “100% solo”, in other words without ropes or belays. They climb alone, they don’t use ropes and, on reaching the summit, they return to the valley by paraglider or hang-glider. One record is shattered after another.

Christophe Profit is one of these mountaineers. On June 30, 1982, he enters mountaineering history by climbing the “American Direct” on the west face of Les Drus in 3 hours and 10 minutes at a time when the best teams of climbers needed a day and half to do it. He is only twenty-one. In March ’85, he climbs the north face of the Eiger in 10 hours after the previous two solo climbs in winter of this same face, by a Japanese and then a French mountaineer, required 8 and 6 days respectively.

In late 1986, he is preparing the “combined” ascent of three of the greatest north faces in the Alps – Les Grandes Jorasses, the Eiger and the Matterhorn – and asks me to make the film that will record this epic undertaking. After shooting on Les Drus, devised as a fiction shoot (a “remake” of his feat of June ’82 for which we needed several days to “re-enact”, shot by shot, the sequence of an ascent that was presented as taking just a few hours), the idea of shooting a film in real time delights me.

In early January, I visit Christophe at home in Chamonix. He is completely focused on the project and prepares for it with painstaking care, helped by Sylviane. A strict diet, daily training: climbing, cross-country skiing, ice falls, running… Eighteen months earlier, he first “combined” these three mythical faces – in 24 hours! – but that was in summer and so “easier”. This time, he thinks it will take 40 hours.

Considered for many years as “the last three great challenges of the Alps”, the north faces of Les Jorasses, the Matterhorn and the Eiger are the most prestigious in eyes of mountaineers of all ages. They have been the setting for legendary and often dramatic adventures in the past and their difficulty, the scale of the climb and the commitment that they require inspires and fuels the imagination of the most audacious climbers. With its wall 5,400 feet high, the Eiger is probably the moist impressive and least hospitable of the three. Vertical and even overhanging for two thirds of its height, this gigantic limestone wall, continually sheathed in ice, is frequently swept by falling rock. The north face of the Matterhorn offers a much more dazzling image. It’s the ideal mountain, a perfect pyramid. But its rock is unstable and its north face too is often swept by rock falls. Finally, the huge barrier, as wide as it is high, that rears above the Mer de Glace, the north face of Les Grandes Jorasses is a series of “mixed” routes, blending ice corridors an rocky spurs, that offer hardly any means of escape.

Using photos and maps, Christophe explains the details of his project. The night before the big day, he will go up to the Refuge du Couvercle, that he will leave around midnight, after sleeping a few hours, to reach the foot of Les Jorasses, that he hopes to start climbing at around 3 in the morning. Once he reaches the summit, hopefully by mid-morning, he will take off by paraglider for Courmayeur, on the Italian side of the Mont Blanc range where a friend will be waiting with a car. They will then return to Chamonix, from where he will take a helicopter to the foot of the Eiger, in the Bernese Oberland. After the north face of “The Ogre” (Eiger) and another paraglider descent, a helicopter will then take him to the Valais… where all he will need to do is climb the Matterhorn! Despite its apparent simplicity, the project’s organization is extremely complex, notably for obscure legal reasons: in theory, a French helicopter has no right to fly over Swiss territory… and vice versa. As for the shooting proper, it’s a real nightmare! Trips by car, chopper flights, customs formalities for the film gear, loading of film stock into the cameras, roping up of technicians for possible drops on the face, meals, hot drinks, sleeping arrangements… there are countless logistic problems that soon lead me to the conclusion that we shall need three independent crews and at least two helicopters, not counting the one that Christophe will need to travel from one mountain to another. We therefore need to revise our budget upwards.

In the meantime, I shoot a little footage of Christophe in training, then return to Paris to start preparation. The problems listed above are compounded by that of the cold. All our attention is focused on the equipment. There is no question of our cameras breaking down halfway. They will be powered by lithium batteries that are designed to withstand temperatures of – 40°. By mid-February, everything is ready. There is till one unknown element however: the weather. The start date will depend on it. The whole crew is on stand-by. Every morning and evening, Christophe calls the weather stations in Chamonix and Geneva airport. I soon discover that we won’t have a monopoly on the images… far from it! Antenne 2, Paris-Match, Europe 1, Swiss French-language television, Equipe Magazine and the mountaineering monthly Alpirando will all be along for the ride. How will Christophe manage to retain the necessary concentration if he has to climb in the middle of a swarm of helicopters? As time passes, the tension increases. My nights are more and more agitated.

On March 9, after three weeks of grey skies, an improvement is announced at last. Good weather, cold and dry. Christophe confirms that the three faces are in top condition: covered with fresh ice, rather than soft and unstable snow. Bingo ! We head for Chamonix. One last meeting. For the hundredth time, we go over the whole operation in detail: car transport, helicopter flights, drop-offs on the face, equipment, camera magazine loading, food, ATA notebooks for customs, accommodation, etc. Each crewmember has very precise instructions. The media are also there: radio, TV, Paris-Match… If we don’t want to step on each other’s toes or fight each other for a place on a helicopter, we need to lay some ground rules between us. This is the first time that a mountaineer will be climbing “live”. We are entering a new era. After years isolated from the media circus, mountaineering is falling prey to it as well.

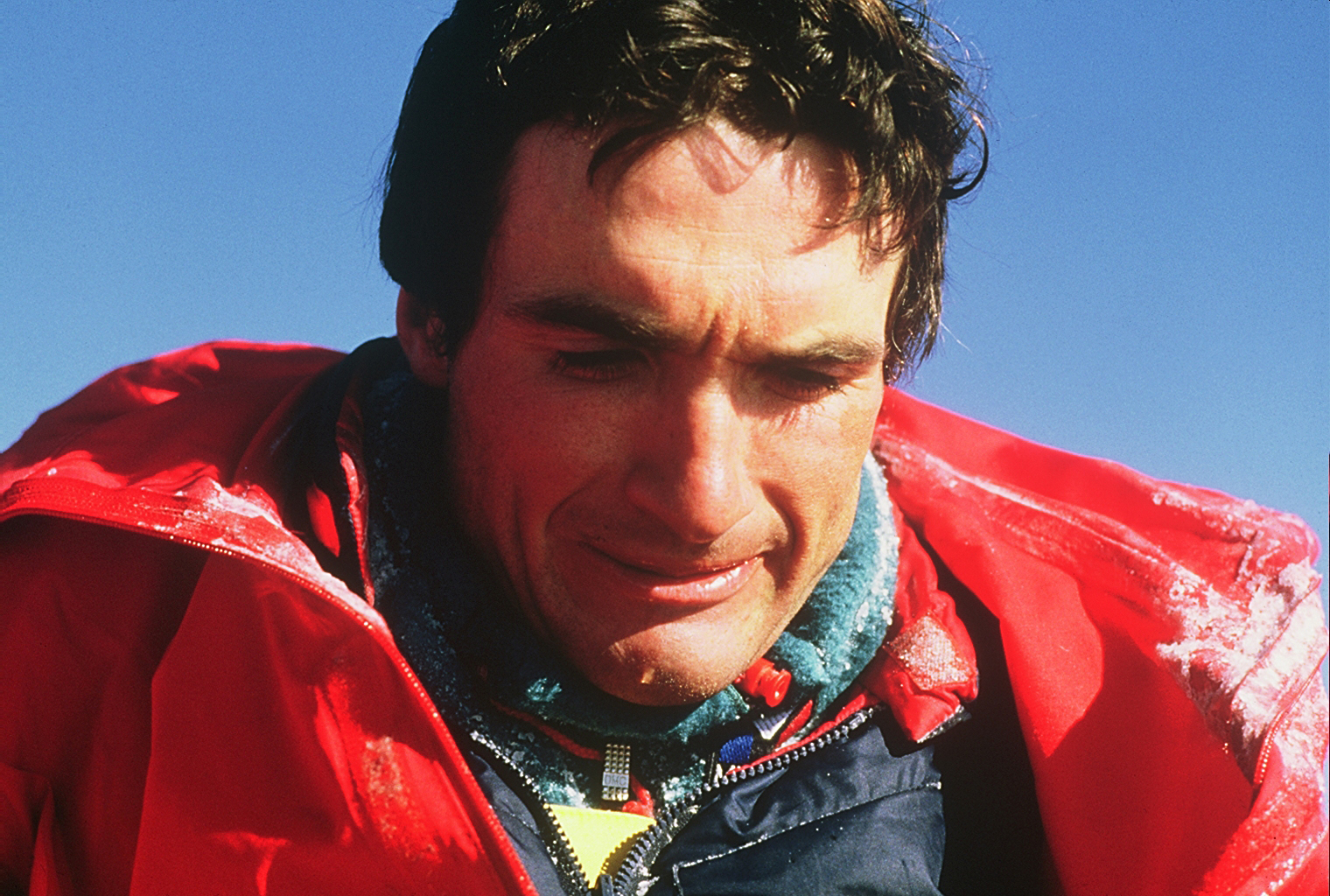

Of course, this will cause a great deal of ink to flow! Some will speak of heresy. Christophe Profit will be criticized for no end of things: using a helicopter, his physical preparation, his painstaking organization and his medical backup comparable to that of a top athlete. He will be accused of turning the mountains into a stadium and of orchestrating the media ballet himself. What of it? His feat remains exceptional for the physical and mental qualities required. What then, a climbing machine, Profit? A hothead? The exact opposite! Sensitive and endearing, Christophe has reached extraordinary heights in the mountaineering world while remaining incredibly normal himself.

Nicolas Philibert

Suspense dans l’Eiger, par Christophe Profit (extraits)

« A 16 heures je démarrais la face nord de l’Eiger. Rapidement je m’aperçois que les cordées qui me précédaient se sont trompées, et je dois faire ma propre trace pour rejoindre le premier passage difficile sous la traversée Hinterstoisser. Il valait mieux connaître ! Arrivé à cette fameuse traversée je rencontre la première cordée : des coréens venus chercher le corps d’un amis disparu à l’automne. Au-dessus, je tombe sur deux anglais tandis que deux hélicos nous tournent autour : un barouf dingue et surtout des coulées par le souffle des pales. Les anglais avaient décidé de redescendre à cause des mauvaises conditions, et moi je continue !-

(…)

Les premières grosses difficultés ont commencé juste avant la nuit, entre le premier et le deuxième névé. J’ai commencé à avoir les boules sur le grand névé ; je l’avais fait une fois en hiver par une neige dure, et là je devais me battre avec une glace noire et dure, vérifier chaque ancrage.

J’ai pris mon mal en patience. Presque arrivé au Fer à repasser j’ai trouvé un autre gros obstacle : des bouchons de neige dans les fissures. Avec la panne du Barracuda j’ai commencé à nettoyer, ce qui m’a pris pas mal de temps. J’ai franchi ce passage d’une longueur pour atteindre le Fer à repasser et à la fin j’avais deux doigts complètement blancs. Je n’avais jamais eu les doigts dans cet état. Je me suis immédiatement arrêté pour les masser. La circulation est revenue et j’ai rejoint le Bivouac de la Mort. J’avais fait une vacation radio au niveau du premier névé, et là j’en ai refait une. Au fur et à mesure je me rendais compte que cela devenait de plus en plus problématique et en arrivant à la Rampe j’ai vraiment pris un coup au moral. Je savais que le problème était là, mais à ce point ! Quand j’ai fait les premiers mètres dans la Rampe je me suis dit que vraiment ce n’était pas possible de grimper dans ces conditions ! J’ai appelé à la radio et je le leur ai dit.

De la Rampe on voit très bien la Kleine Scheidegg, l’hôtel où ils étaient, et jamais je n’avais perçu avec une telle acuité le contraste entre la vie là-bas et moi dans une situation aussi précaire. Je leur parlais à la radio et pour un rien, une demi seconde après je pouvais me casser la figure et débouler 1000 mètres de paroi. Je pouvais leur parler, me confier et en même temps j’étais en plein vide sur mes pointes de crampon accrochées à des bouchons de neige branlants : ça m’a fait tout drôle. J’ai continué dans La Rampe en faisant super gaffe. Je me souviens notamment d’un passage dont trois fois de suite je me suis approché, revenant à chaque fois en arrière sans oser le tenter tellement cela me paraissait tangent. Je n’avais aucune possibilité de m’assurer, tout était recouvert de neige et j’étais obligé de passer au moral. Là j’ai eu le sentiment de jouer à la roulette russe, j’étais sur les pointes de mes crampons et tout pouvait arriver. La radio c’était mon paquet de cigarettes, c’était instinctif, je ne pouvais m’empêcher d’appeler. Ensuite je suis arrivé au passage clé de La

Rampe, la fissure: là c’était carrément sordide. Trois bouchons successifs barraient la fissure, une neige bien durcie.

Il n’y a pas d’autre passage. Il fallait nettoyer : j’ai mis une heure trente pour tout dégager sur vingt mètres. Je trouvais des pitons au fur et à mesure donc je pouvais m’autoassurer. Pour l’un des bouchons j’étais dessous à essayer de dégager la neige et d’un seul coup un énorme bloc m’est tombé sur la nuque.

(…)

Dès les premières lueurs du jour, je me suis lancé dans la Traversée des Dieux : c’est vertigineux et j’ai pris le temps de m’assurer. Je suis arrivé à l’Araignée : c’était une étape, le moral allait mieux. Ensuite les fissures de sortie m’ont posé moins de problèmes que je ne le craignais. Je me sentais fatigué, sans plus. C’est en arrivant sur l’arête sommitale que j’ai eu le gros coup de barre. Je m’arrêtais tous les dix mètres. A 9 h 30, en arrivant au sommet où Sylviane m’attendait, j’ai complètement craqué. Je me suis mis à pleurer. Puis je suis arrivé près de l’équipe cinéma et je sanglotais. Je pouvais me laisser aller : pour moi c’était gagné. Je sortais vivant d’une nuit de cauchemar et c’était un immense bonheur. Elie Hanoteau m’attendait avec mon parachute. Le vent avait forci et il m’a dit que le décollage ne serait pas évident. Je n’ai pas hésité, j’étais en hypothermie. J’avais les joues blanches, mon pantalon était dur comme du bois, j’étais très marqué et j’ai estimé que c’était trop dangereux dans ces conditions de partir en parapente… »

« Bien sûr, le réalisateur ne s’est pas privé de ces images fantastiques d’un homme seul dans l’immensité rocheuse, de ce ballet irréel d’un alpiniste dansant à la verticale sur une paroi de glace, un piolet dans chaque main et des crampons aux pieds, de ce travelling étourdissant autour de Christophe Profit « sortant » des Grandes Jorasses ou de sa vertigineuse descente pendu sous un parapente multicolore. Mais il a su aller au-delà et saisir ces petits gestes, ces paroles sans importance, qui donnent sa dimension humaine, la vraie, à l’exploit. Paradoxalement les images les plus lumineuses de ce film sont celles qui illustrent l’ascension nocturne de l’Eiger. Christophe Profit n’est plus à l’écran, mais il est autrement présent, par le seul lien qui l’unit à sa compagne Sylviane, un talkie-walkie. Un filet de voix sort des ténèbres, « J’ai froid aux pieds ! » et la solitude du grimpeur, le silence et le froid, le sommeil et l’épuisement deviennent évidents. »

« Avec trois équipes de tournage, 10.000 mètres de pellicule et 15 heures d’hélicoptère, Philibert dissèque tous les préparatifs de Profit. Une équipe dans la paroi, l’autre au sommet qui se relaient en permanence. Dans la nuit du 12 au 13, Christophe connaît de grandes difficultés dans l’Eiger. Froid et lampe électrique en panne. Le retard s’accumule. Au sommet Christophe porte les stigmates d’une nuit d’enfer. Tout le monde l’entoure comme un nouveau né. Plan après plan Trilogie pour un homme seul est un film d’amour. »

« … Tout y est. La chronique d’une passion, l’histoire d’une obsession, l’aventure d’un couple, le portrait d’une solitude, et l’observation du grand cirque médiatique. Plus il y a de monde autour de Christophe Profit et plus il est seul. Au-delà des formidables images de montagne de l’ascension métronome du Croz ; de la performance technique du ballet caméra / hélico / parapente (bravo à l’opérateur et au pilote), de l’émotion dans la nuit de l’Eiger ; je garderai une image. Celle de ce petit grand homme en lévitation, tout seul au sommet des Grandes Jorasses ; la caméra qui s’éloigne et qui révèle le gros insecte vrombissant à quelques mètres ; et l’alpiniste qui paradoxalement semble encore plus seul. La majeure partie du film a été tourné en direct, comme un grand reportage, et pourtant Philibert sort de son chapeau une histoire d’amour. »